Ethel Mary Bullock, “Miss Boo” and her private Deaf School(s)

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 15 September 2017

Ethel Mary Bullock was the daughter of a linen draper, Francis Bullock and his wife Annie. She was born in Marylebone in 1870, probably in 72 Edgeware Road, where they were living in 1871 and in 1881. By 1881 the family had grown quite large, with ten surviving children. Ethel became a teacher of the deaf, training to use the oral oral method under van Praagh in Fitzroy Square Training College. She qualified in 1890 (for this & what follows, see the obituary by Ross, 1962).* In the 1901 census, when she was 31 and living with her older sister and widowed father at the same address, she was described as a ‘deaf mute teacher.’

Ethel attended the 1903 National Association of Teachers of the Deaf conference, and at that time she was living in Brook Green, near Hammersmith, but after a quick glance at the lists of delegates at later conferences through the next two decades, I did not spot her name again.

In 1903 she opened her own school in Chiswick, where the 1907 to 1909 phone books have her name in large print as a ‘Certified Teacher of Deaf (Oral System), Defects of Speech, Stammering &c., Lip-reading.’ The school in Chiswick was at 45 Fairlawn Avenue, which was and still is an ordinary suburban house. I suppose she moved there from Brook Green. From Chiswick, at some point the school moved on to Hampstead, in fact what we would now call Swiss Cottage, at 141 Fellows Road. The 1911 census has her there but she made a mess of the form, putting herself as head of the household down the list of six inhabitants, and filling in the box which was left for the enumerator. The teaching staff are described as ‘Educational’ in the occupation column, and there was only one pupil living in who was not described as deaf. Perhaps she was just setting up the school again or was only taking day pupils. She was still there in the 1919 phone book, but the following year finds her in Ashdown House, Rosslyn Hill, N.W.3. **

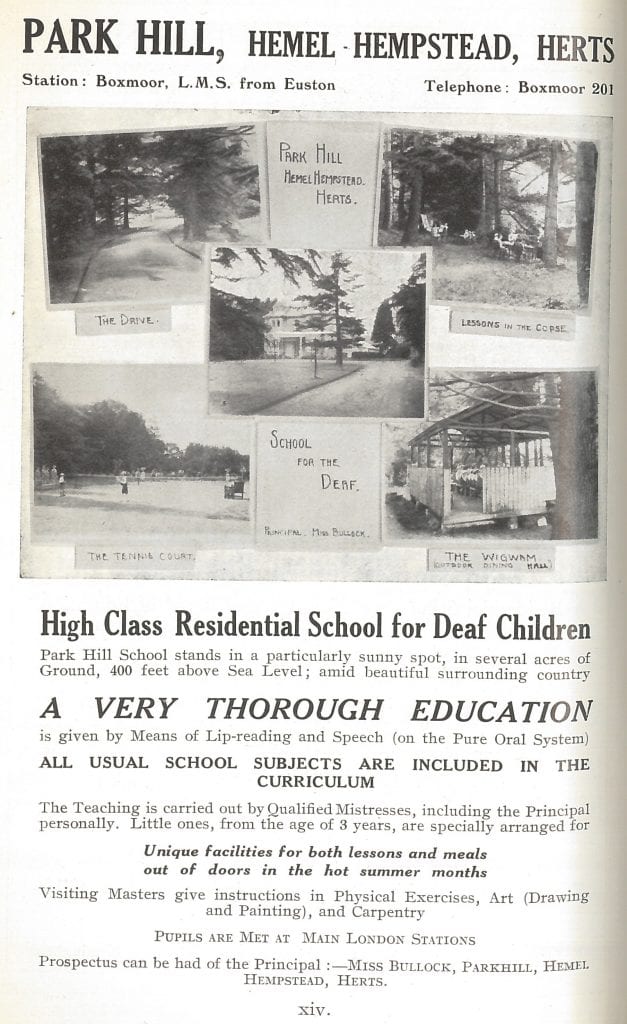

By 1923 the school had moved again, and the phone book for that year gives her address as Kingsfield House, Oxhey, near Bushey, Herts. Oxhey is now a suburb of Watford. Here was see the advertisement for the school in the front of the proceedings for the International Conference on the Education of the Deaf for 1925.  It was there at least until 1927, but by the 1930s the same building had become a boys school and, yes, they had moved yet again, to Park Hill, Hemel Hempsted, where the school was definitely re-established by 1929. The school looks superficially similar to the Kingsfield site, in park-like grounds, and it looks from the photos as if they even moved the ‘wigwam’ – their outdoor teaching hut (All About the Deaf p.xiv).

It was there at least until 1927, but by the 1930s the same building had become a boys school and, yes, they had moved yet again, to Park Hill, Hemel Hempsted, where the school was definitely re-established by 1929. The school looks superficially similar to the Kingsfield site, in park-like grounds, and it looks from the photos as if they even moved the ‘wigwam’ – their outdoor teaching hut (All About the Deaf p.xiv).  Miss Bullock must have only ever had short leases on these places, for yet again the school moved, to Folkestone at a date in the 1930s which I cannot pin down, then on to “Ingleside,” Tilehurst Road, Reading, where the school was in 1939 (All About the Deaf, p.66). I cannot imagine it survived for long after the outbreak of war, and by the time we find Ethel next, in the 1947 telephone directory, she was living at 25 The Roystons, Surbiton.

Miss Bullock must have only ever had short leases on these places, for yet again the school moved, to Folkestone at a date in the 1930s which I cannot pin down, then on to “Ingleside,” Tilehurst Road, Reading, where the school was in 1939 (All About the Deaf, p.66). I cannot imagine it survived for long after the outbreak of war, and by the time we find Ethel next, in the 1947 telephone directory, she was living at 25 The Roystons, Surbiton.

It is very interesting that the school moved so often. In her brief appreciation of Bullock, Miss J.P. Ross says,

Far from interfering with continuity of progress, these changes of environment proved helpful to the children’s interests and development. This was largely due to the systematic language course , originally introduced by Miss Nevile, which was followed throughout the school, and which produced most gratifying results.

Miss Bullock, who was affectionately known as “Miss Bo,” had a genius for obtaining the best efforts from both pupils and staff, who were always willing to respond to her high ideals.

Ethel Bullock died aged 92 on the 25th of March, 1962, at a nursing home in Surrey. She was an almost exact contemporary of Blanche Nevile, who also trained at the Fitzroy Square Training College, and who also died in 1962. The big question for me, is why did she move premises so often? It is hard to gauge how successful she was as a teacher, for we cannot know now how many pupils she had or who they were, unlike some of the earlier private schools where pupils are named in census returns.

*At the time of the 1891 census she was a visitor in Scotland, with no job description given.

**Incidentally, her younger brother Albert, who was an architect, also has his phone number in New Bond Street on the same pages as Ethel.

Ross, J.P., Miss Bullock. The Teacher of the Deaf 1962, vol. lx no. 357 p.279

Census 1871 – Class: RG10; Piece: 165; Folio: 63; Page: 6; GSU roll: 823301

Census 1881 – Class: RG11; Piece: 147; Folio: 17; Page: 27; GSU roll: 1341033

Census 1901 – Class: RG13; Piece: 110; Folio: 72; Page: 31

Census 1911 – Class: RG14; Piece: 615

International Conference on the Education of the Deaf, London and Margate, 1925.

National Bureau for Promoting the General Welfare of the Deaf, Handbook for 1913, also N.I.D. All About the Deaf handbooks for 1929, 1932 and 1939.

Close

Close