Annie Scandrett of Liverpool – a supposed miracle cure of a ‘deaf’ woman, 1923

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 19 July 2019

In 1923 the Roman Catholic Diocese of Lancashire sent a group of people to the shrine at Lourdes with Archbishop Keating. Among them was a soldier, Jack Traynor, badly wounded in the war, and supposedly a man who was then miraculously cured. The visit was filmed as a short reel film called “Our lady of Lourdes” and was shown in cinemas in Liverpool.

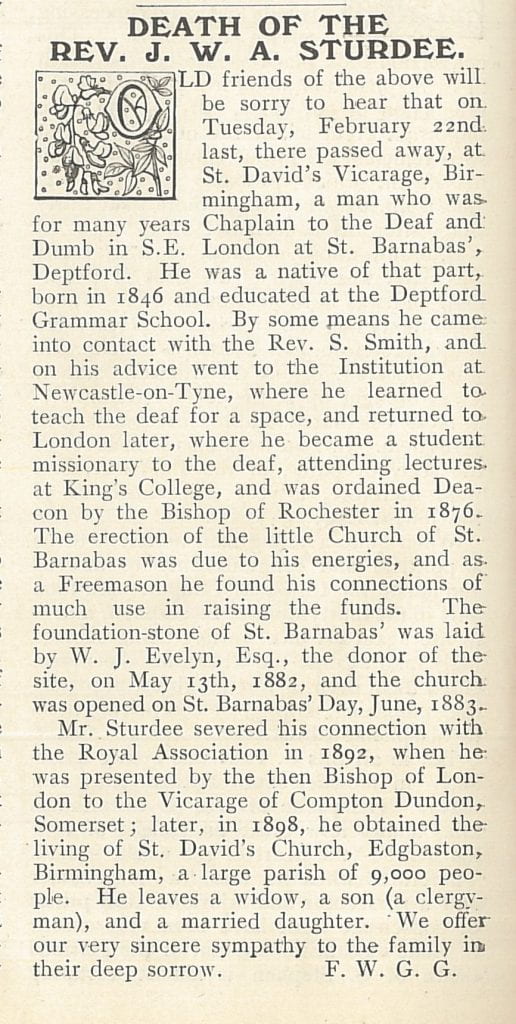

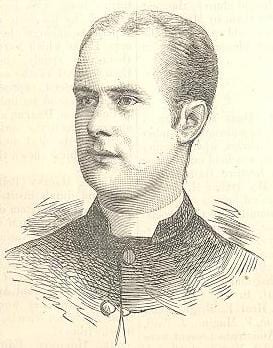

One story in the Liverpool Echo, has a photo of Traynor and Scandrett, with the following note –

WALKING AND HEARING AFTER LOURDES.

Mr. Traynor. of Liverpool, who was taken to Lourdes in a bathchair, pacing the deck of the Channel boat on the way home, chatting with Miss Scandrett, also of Liverpool, who says Lourdes has cured her of her deafness. Mr. Traynor, an ex-naval man, was wounded in the war, and paralysis followed. Miss Scandrett had been practically deaf for 12 years.

Traynor is only of passing interest to us as he was not deaf, and I have nothing to say about his ‘miracle,’ but Annie Scandrett is worth investigating a little more.

Traynor said to the Rev. Patrick O’Connor,

a Protestant girl from Liverpool had come to the Continent on a holiday tour. She got tired of all the usual show places and happened to come to Lourdes. She was a trained nurse and, seeing all the sick, she offered her services to help in the ‘Asile.’ Her parents in England, upset at her decision to stay as a volunteer worker in Lourdes, sent out her sister to keep her company. The two girls went down to see the Liverpool pilgrims. They remembered having seen me sitting in my wheelchair outside my house at home and they volunteered to take care of me. I gladly accepted their kind offer, and they washed and dressed my sores and looked after me during my stay in Lourdes. (see I Met a Miracle)

Note that he fails to mention her name, even though he knew it. Annie was born in Liverpool on the 24th of September, 1884. At some point the family moved to Aston, Birmingham, where she was living still in 1911. The film seems to have been propaganda for the church. At one film showing at the Egremont, Annie was persuaded to stand up and talk (The Bioscope). It would be interesting to know if the film still exists.

The film seems to have been propaganda for the church. At one film showing at the Egremont, Annie was persuaded to stand up and talk (The Bioscope). It would be interesting to know if the film still exists.

Her story was revived in 2016 when a former neighbour spoke to a local paper. He related what Annie had said –

She said she had been sat by his bedside in his room one day when a white dove came through the window and circled right round. It then landed on the headboard of the bed. Annie had been deaf but the next morning when she went down to breakfast she realised she could hear again. The first words she heard were ‘please can you pass the butter’.

Traynor does not mention a dove, the accepted typical bird of ‘miracles,’ representing the holy spirit.

It certainly seems curious that she chose to holiday in the area in 1923, as it was quite unusual for working people to go on holiday to the continent at that time, so I suspect that her visit was planned, but of course we cannot know now.

There is no mention of deafness on any of the three census returns. She claimed her ‘deafness’ had lasted for twelve years, from around 1911. If we had the 1921 census that might be revealing, however her ‘deafness’ is undefined, and I would suggest that she probably was never ‘deaf’ as we might understand it. At any rate we can agree that it was probably a defining moment in her life.

Annie lived in Norris Green, Liverpool, until her death in 1961.

1891 census – Class: RG12; Piece: 2422; Folio: 132; Page: 25

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 2885; Folio: 104; Page: 9

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 18328

1939 Register – RG 101/4390D

The Bioscope – Thursday 13 September 1923 p.64

Liverpool Echo – Monday 30 July 1923 p.6

The above picture is from our photo collection – Probably from the Liverpool Daily Post.

Close

Close