Harry Wellington White was born in October, 1854, son of Wellington White, a ‘quartermaster of militia,’ born in Tipperary, and his wife Anne, from Kildare. The oldest sister was born Van Diemen’s Land, then a brother was born in Dover, a second brother was born in Lancashire, and his younger brother in Hampshire, so presumably the father was being sent around the empire for his work.

Harry Wellington White was born in October, 1854, son of Wellington White, a ‘quartermaster of militia,’ born in Tipperary, and his wife Anne, from Kildare. The oldest sister was born Van Diemen’s Land, then a brother was born in Dover, a second brother was born in Lancashire, and his younger brother in Hampshire, so presumably the father was being sent around the empire for his work.

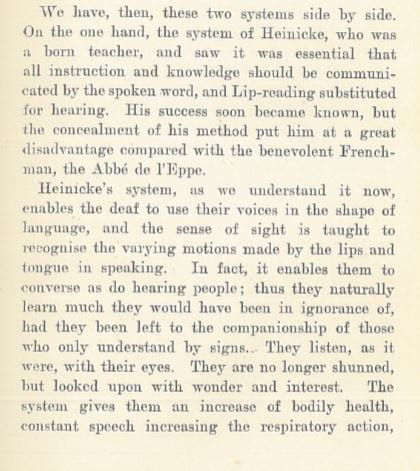

Harry White began working as a clerk, presumably when he left school. He was employed as a clerk in the offices of the Great Western , at General Manager’s office at Paddington in November, 1876. He remained an employee there until February, 1879, when he resigned. He would then be aged a little over 24, and we might suppose that it was then, or shortly after, that he enrolled as a trainee teacher of the deaf at the Ealing ‘Society for Training Teachers of the Deaf and for the Diffusion of the German System.’ He took a two and a half year course there, and qualified in 1881 in the same cohort as Mary Smart, and was it seems the only male teacher to qualify there, which seems extraordinary. I seem to recall reading somewhere that there were far fewer me interested in becoming teachers in the latter years of the 19th century. Previously I think male teachers had often gone into teaching as pupils who became teachers, then learnt on the job in deaf schools, but this would require research to confirm.

Having qualified, he was appointed Vice-Principal under Arthur Kinsey. He was sent out from Ealing as an acolyte, and Benjamin St. John Ackers who lead the society as Honorary Secretary, wrote in the annual report for 1884 (p.10) –

Somewhat earlier in the year your Honorary Secretary attended the Annual Meeting of the Manchester Schools for the Deaf and Dumb, as a subscriber to that Institution, where it will be remembered Mr. H. W. White, our late Vice-Principal, was engaged in the work of training the teachers employed there, to carry on the German System. Mr. White had represented to your Society that certain changes in the arrangements of the Manchester Institution were absolutely necessary for the ultimate success of the work. Your Honorary Secretary’s attendance, upon the occasion referred to, was to urge the adoption of these proposed changes upon the Manchester Committee, and also the further engagement of Mr. White for another twelve months ; this latter proposition, we are sorry to learn, has, from want of funds, not been accepted. The period of Mr. White’s engagement with your Society having expired, we were in strong hopes of seeing him at the head of some British Institution, carrying on successfully the work for which he has been trained. About this time the Head Mastership of the West of England Institution, at Exeter, fell vacant, and Mr. White was at once advised to apply for the post, but he did not feel at liberty to do so. Shortly afterwards a similar vacancy occurred at the Liverpool Institution ; again he was urged to apply. Owing, possibly, to delay in forwarding his application, he was not successful in obtaining the appointment. Upon the termination of the Society’s agreement with Mr. White an agreement was executed with Mr. Alfred Batchelor to train at the College, and to give his services to the Society in such ways as might be required for their work.

The Manchester Schools Sixtieth Annual Report for 1884 (we have not got the 1883 Report) tells us that “the arrangement referred to in the last Annual Report as having been made with Mr. White, Vice-Principal of the Ealing College, is being brought to a satisfactory termination ; and it is gratifying to your Committee to find that the Oral Classes, as organised by their Head Master, [W.S. Bessant] are working so nearly upon the lines laid down by Mr. White in his lectures, that very little alteration in them has been rendered necessary. (Annual Report, 1884, p.6).

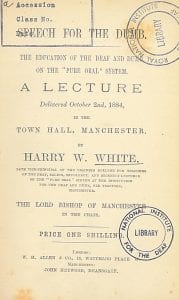

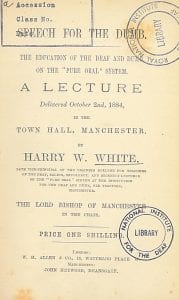

It seems Ackers was, however, rather disappointed with White. He wanted to expand the oralist approach by getting his man into a big school. Perhaps White felt that running a private school would be more rewarding. In October, 1884, White published a booklet with W.H. Allen, publishers, Speech for the Dumb. The Education of the Deaf and Dumb on the “Pure Oral” System.

He laid out the oralist approach, and concluded with an appendix on ‘Hints for the management of a deaf child.’ This included ‘Do not allow him to shuffle his feet when walking.’ Interestingly, one of our regular visitors tells me that she was told the same thing at school – perhaps this was part of the long legacy of the Ealing College? In the introduction to that essay, when he was living at 3, Blenheim Terrace, Old Trafford, Manchester, he says, (p.v) that “I am desirous of opening a small private and select school for deaf children of the higher classes, at Bowden, Cheshire.” Of course he adds, needlessly, “signs and the manual alphabet being rigidly excluded.”

He laid out the oralist approach, and concluded with an appendix on ‘Hints for the management of a deaf child.’ This included ‘Do not allow him to shuffle his feet when walking.’ Interestingly, one of our regular visitors tells me that she was told the same thing at school – perhaps this was part of the long legacy of the Ealing College? In the introduction to that essay, when he was living at 3, Blenheim Terrace, Old Trafford, Manchester, he says, (p.v) that “I am desirous of opening a small private and select school for deaf children of the higher classes, at Bowden, Cheshire.” Of course he adds, needlessly, “signs and the manual alphabet being rigidly excluded.”

I am not sure if that school got going, as by July 1885 he was offering lip reading lessons and his address was 4 Osman Road, West Kensington Park. Not long after, we find numerous advertisements for White’s private deaf school, at 115 Holland Road, Kensington, in The Times and London Evening Standard (see British Newspaper Archive), as well as mentions in The Lancet (by February 1886). He was, that same year one of the witnesses for The Royal Commission on the Blind, the Deaf and the Dumb (1889). (We have the full text, and electronic access through Parliamentary Papers database.) He was asked about his time at Manchester on Thursday the 18th of March, 1886. You may recall that Ackers was on the commission, so I do not think it would be unfair to say that there was already an oralist bias –

7969. When you first went there was that the commencement of the change ? — No, they had endeavored to introduce the system, and I suppose it would be

maintained that they had introduced it. Of course one is very delicate upon a matter of that kind; there are certain susceptibilities to consider; I think they claimed that they introduced the system; but I went there to assist them to carry it on to probably a higher pitch, and farther extent.

7970. Do you claim that you made great progress is the teaching of the teachers there ? — Undoubtedly.

7971. And also the pupils themselves ? — Certainly. Of course my individual efforts could not have shown very great results in the children except through the teachers that I trained. I could not be expected to teach 160 children, nor would my results be very much in twelve months; but I think that, taking class and class with the teacher that was attached to it, the whole tone of the training showed itself clearly in the education of the children.

Further on he says (paragraph 8007),

When I went to Manchester, of course the tone of the institution was undoubtedly sign. From the point of view of a pure oral teacher it was like a fever lurking about (that is a rather strong way of putting it), and it wanted removing before you could expect to do anything with the children on the opposite system.

8008. You mean tho fever of the sign system ? — From our point of view, though that is rather a strong way of putting it; but it certainly was very infections. The new children and the children taught on the oral system were very prone to fall into the ways of those who had a system of signs around them. The consequence was that I saw it rapidly running through the whole institution. In six weeks or two months the children who had newly entered were as full of signs as thosewho had been there for six years, though probably not knowing so many signs. The only hope of introducing the pure oral system would have been the removal of the whole of those sign children, and that is what I advocated. I wrote a letter to tho committee and advocated the taking of a new house somewhere in the neighbourhood for the purpose; but they said that they could not possibly do it, that the expense was more than they could meet, and that things would have to go on as they were going on.

[…]

8059. Do you think that the time will ever come when the sign and manual systems will disappear altogether ? — I see no reason why they should not.

8060. Do you think there is every reason why they should ?—At present there are very few reasons why they should. If the Government take the matter up and grant assistance to the work, I see every reason why the sign system should be stamped out, and the oral system entirely established in its place.

In both the 1861 and 1871 census records, Harry White was living at home with his parents in 7 Hackney Terrace, Cassland Road. He moved with them at some point after that, to 3 Poplar Grove, Hammersmith. In January 1891 he married Emma Parrell, at St Mary Magdalene, Peckham, and at that time he was described as a teacher on his marriage certifiate, but in the 1891 census a ‘Teacher of the Deaf’. In both the 1901 and the 1911 censuses, they were recorded as living in 13 Sinclair Gardens, Hammersmith.

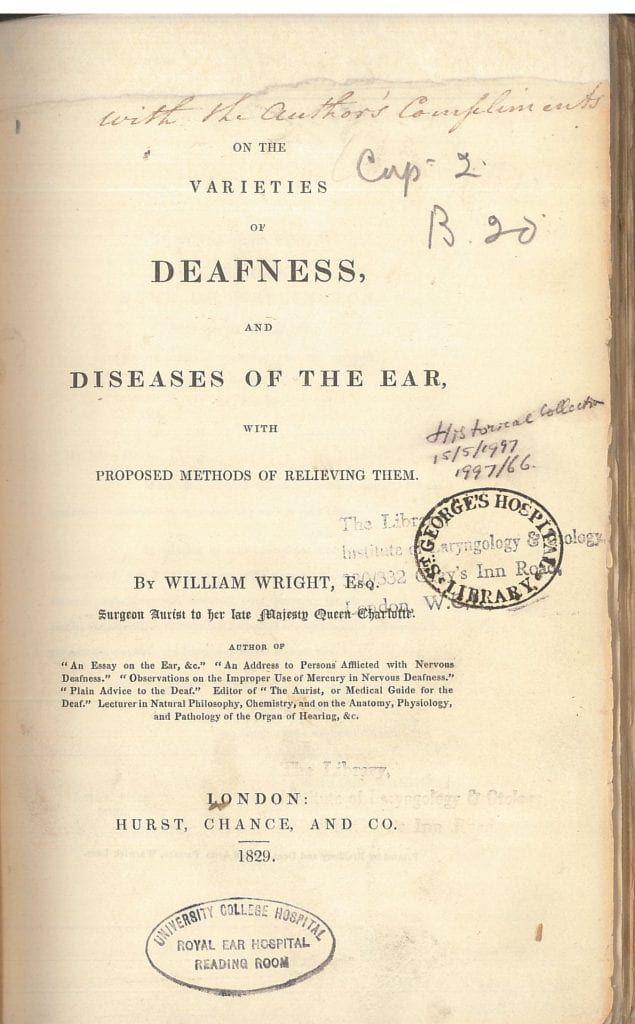

After some years he seems to have turned away from being purely a teacher of the deaf, though he may well have still had deaf pupils, for he describes himself as ‘Speech Specialist’ in both 1901 and 1911 census returns. He wrote a few other short items, one we have, The Mechanism of Speech (1897), and a book we do not have, Hearing by Sight (18-?) which is held in Aberdeen University, possibly a unique copy.

I cannot say anything of his later carreer, but that he had three children, one son who attended Cambridge university (Harry Coxwell White), and that he died in 1940.

The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Collection: Great Western Railway Company: Staff Records; Class: RAIL264; Piece: 6

1871 Census – Class: RG10; Piece: 332; Folio: 73; Page: 58; GSU roll: 818902

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 60; Folio: 19; Page: 32; GSU roll: 1341013

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 39; Folio: 182; Page: 34

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 50; Folio: 21; Page: 33

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 255

The Times (London, England), Wednesday, Oct 21, 1885; pg. 2; Issue 31583.

The Standard (London, England), Tuesday, July 14, 1885; pg. 8; Issue 19032

You can read the whole (short) book on the wonderful Project Gutenberg.

You can read the whole (short) book on the wonderful Project Gutenberg. Close

Close