A CODA – Child of Deaf Adults – Lon Chaney

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 20 April 2018

Many children of deaf people are hearing. In deaf studies they are sometimes called CODAs – Children of Deaf Adults. Being a CODA has its own set of issues and problems growing up, but it also has some advantages. A CODA child will often be roped in to interpret between parents and officials, doctors, or the world in general, but it can also give them a foot in two cultures. One example mentioned many times in these blog pages, is the Rev. Fred Gilby. His parents were to discover that he was not Deaf, and he learnt to sign when other children were beginning to speak (memoirs p.8).

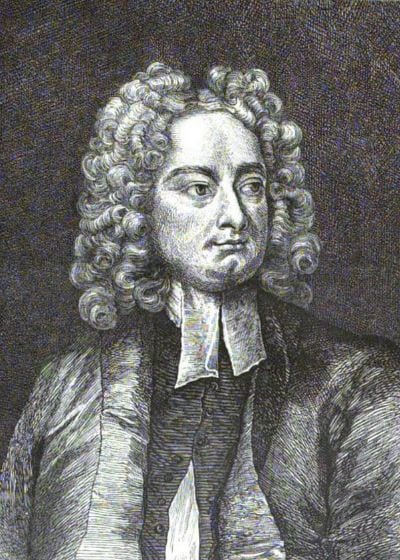

Another such child, was the famous actor, Leonidas Frank “Lon” Chaney (1883-1930). His mother, Emma, was Deaf, the daughter of Jonathan Kennedy, a farmer from Illinois, and from the birthplaces of his children you can see how their family typified the movement of settlers west onto the prairie; Ohio, then Kansas, then Emma married in Colorado where Lon was born. Emma’s sister Matilda and brother Orange were also Deaf. Jonathan Kennedy founded the Colorado Deaf School in 1874, no doubt because of his Deaf children. We have some U.S.A. institution annual reports, but not those for Colorado unfortunately.

Chaney’s father, Frank, a barber, was also Deaf, and born in Ohio. He met Emma at the Colorado school. It seems that Chaney was a very private man, and there are many gaps in his early life, where comparatively little is known.

It may be that his facial expressiveness was part of a skill set he acquired when communicating with his parents, then used in his theatrical life. He certainly put his abilities to great use in silent films, portraying, for example, the deaf Quasimodo, in the 1923 film, The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

I have not had time to delve into his life, so I cannot say whether he was a true signer or not. If you know, please comment with a source for any reference and I will update this.

Lon Chaney, the ‘Man of a Thousand Faces’ (source of photo unknown)

Lon Chaney, the ‘Man of a Thousand Faces’ (source of photo unknown)

If you know the song ‘Werewolves of London,’ you may recall he gets a mention –

If you know the song ‘Werewolves of London,’ you may recall he gets a mention –

“Well, I saw Lon Chaney walking with the Queen

Doing the werewolves of London,

I saw Lon Chaney, Jr. walking with the Queen,

Doing the werewolves of London”

Lon Chaney was the Phantom of the Opera, and his son was the Wolf Man.

See www.ancestry.co.uk for his family tree

Close

Close

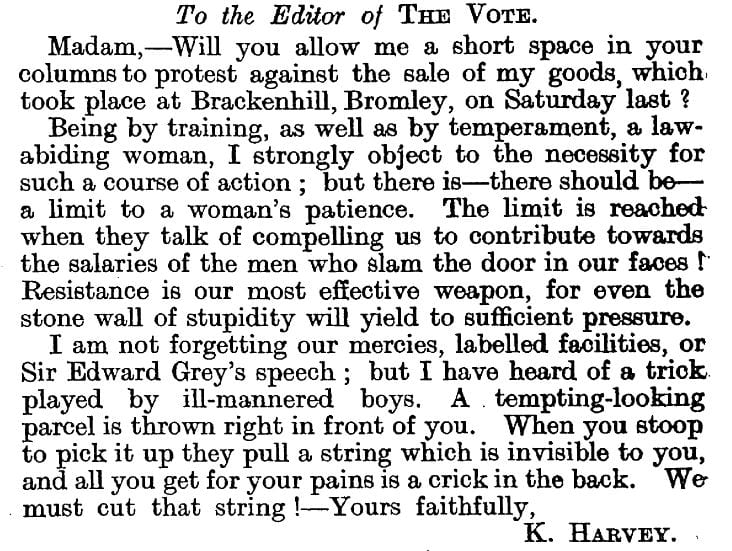

Article from The Vote, June the 17th, 1911

Article from The Vote, June the 17th, 1911