“Such is the calamity of Mortals in this state of misery” – Sibiscota’s Deaf and Dumb Man’s Discourse

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 7 August 2015

Such is the calamity of Mortals in this state of misery, that they are invaded on all sides not only when they are born, by a vast army of Diseases, but are also troubled with many distempers whilst the Womb is their Lodging; there we meet with the precursory messengers of Death even in the very beginning of Life; and whilst the formative faculty is framing this machin of our immortal souls, some deformity, some irregularity in the structure, or other preternatural disposition obstructing the exercise of the parts immediately intermixeth it self with our birth. Which enormity of the the parts, or constitution repugnant to the Lawes of Nature, prejudicing the operations, and contracted at our Birth, some have been so scrupulous as to think that it ought not to be calculated by the name of a Disease, but of a Defect, reserving the name of Disease for the defects of that which was once perfect.

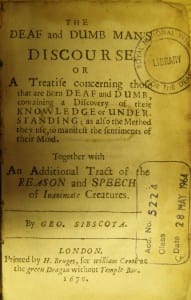

This is the opening page of The Deaf and Dumb Man’s Discourse or A Treatise concerning those that are born deaf and Dumb, containing a Discovery of their Knowledge or Understanding; as also the Method they use, to manifest the sentiments of their Mind (1670). It was supposedly written by George Sibscota, but was a loosely translated version of Anthony Deusingen’s “Dissertatio de surdis,” an essay in Fasciculus dissertationum selectarum (Gröningen, 1660) (see here). Sibscota is probably a pseudonym.

This is the opening page of The Deaf and Dumb Man’s Discourse or A Treatise concerning those that are born deaf and Dumb, containing a Discovery of their Knowledge or Understanding; as also the Method they use, to manifest the sentiments of their Mind (1670). It was supposedly written by George Sibscota, but was a loosely translated version of Anthony Deusingen’s “Dissertatio de surdis,” an essay in Fasciculus dissertationum selectarum (Gröningen, 1660) (see here). Sibscota is probably a pseudonym.

The writer is of course depicting deafness as a defect. The usual problem to many in the pre-modern age, and was how these who were deaf could achieve religious salvation:

And as Faith comes by Hearing, [*] according to the Apostle, where this is wanting, it may possibly seem very agreeable to truth, that there can be no Faith, and therefor no saving knowledge; and the consequence is undeniable, since no man can be saved without faith.

Oh this is indeed a very hard saying, which shipwracks the Soul! Truly since those that are born Deaf are no more guilty of neglecting the means of their Salvation , than Infants (concerning whom however the Sacred Pages advise us to be more charitable) what reason I wonder can there be, why we should think God less merciful to them, who are also born of faithful Parents, than to Infants! We will leave the disquisition of their Faith, or the manner thereof to Divines. Hath God therefor, who according to his Will hath elected some out of Mankind corrupted by the fall, to be Vessels of mercy, and others Vessels of wrath? Yet God’s Promise and Covenant belongs to these, as much as to the children of the faithful.

[…] Yet God is not wholly tied up to this one way of operation. He hath extraordinary ways which we are ignorant of […]

They therefore that are born Deaf may by writing inform their minds with knowledge of those things, which must be obtained by hearing in others […] (ibid p.36-7 and 39)

The author does however note that “experience teacheth us, […] that those that are originally Dumb, and Deaf do by certain gestures, and various motions of the body as readily and clearly declare their mind, to those with whom they have been often conversant, as if they could speak, and likewise by such gestures of other Persons, they do absolutely understand the intentions of their mind also.”

* Romans 10:17

Branson, Jan, and Miller, Don, Damned for Their Difference: The Cultural Construction of Deaf People as Disabled, 2002

Cocayne, Emily, EXPERIENCES OF THE DEAF IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND, The Historical Journal, 46, 3 (2003), pp. 493–510

Woodward, James, How You Gonna Get to Heaven If You Can’t Talk With Jesus: On Depathologizing Deafness, 1989

Winzer, Margret A., The History of Special Education: From Isolation to Integration, 1993

Close

Close