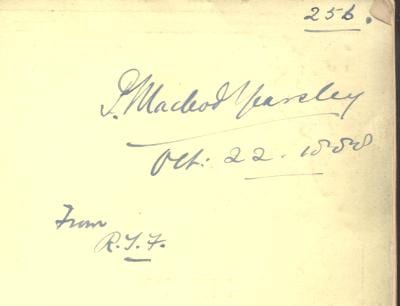

“Breeders of the Deaf” – Percival Macleod Yearsley’s ‘self advertisement’

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 22 March 2016

In the 1920s eugenics was a very hot subject, an area of much concern to Percival Macleod Yearsley (1867-1951). Percival was a cousin (twice removed) of James Yearsley the great aural surgeon. Yearsley was formerly consulting aural surgeon to St. James’ Hospital, Balham, and to the London County Council. He died at Gerrard’s Cross on May 4, 1951 at the age of 83. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and the Westminster and London Hospitals. In 1893 he was appointed to the staff of the old Royal Ear Hospital in Soho, becoming senior surgeon, and

In the 1920s eugenics was a very hot subject, an area of much concern to Percival Macleod Yearsley (1867-1951). Percival was a cousin (twice removed) of James Yearsley the great aural surgeon. Yearsley was formerly consulting aural surgeon to St. James’ Hospital, Balham, and to the London County Council. He died at Gerrard’s Cross on May 4, 1951 at the age of 83. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and the Westminster and London Hospitals. In 1893 he was appointed to the staff of the old Royal Ear Hospital in Soho, becoming senior surgeon, and

he was the first aural surgeon to the London County Council, for whom he carried out important investigations among school-children. He also interested himself in the welfare of deaf-mutes. A man of many interests, Macleod Yearsley wrote some delightful fairy tales, studied the story of the Bible, discussed the sanity of Hamlet and doctors in Elizabethan drama, took a scientific interest in the Zoological Society, translated Forel’s Sensations des insectes, and was an archaeologist of repute. In his own specialty he wrote a Textbook on Diseases of the Ear (1908) and another on Nursing in Diseases of the Throat, Nose and Ear. Later he became greatly interested in the Zund-Burguet electrophonoid treatment of deafness, on which he wrote a monograph in 1933. Energetic, open-minded, and many-faceted, he was looked upon as rather a stormy petrel by his contemporaries; but he mellowed with time, to be regarded with respect and admiration by otologists of today. (Obituary in the Lancet, 1951)

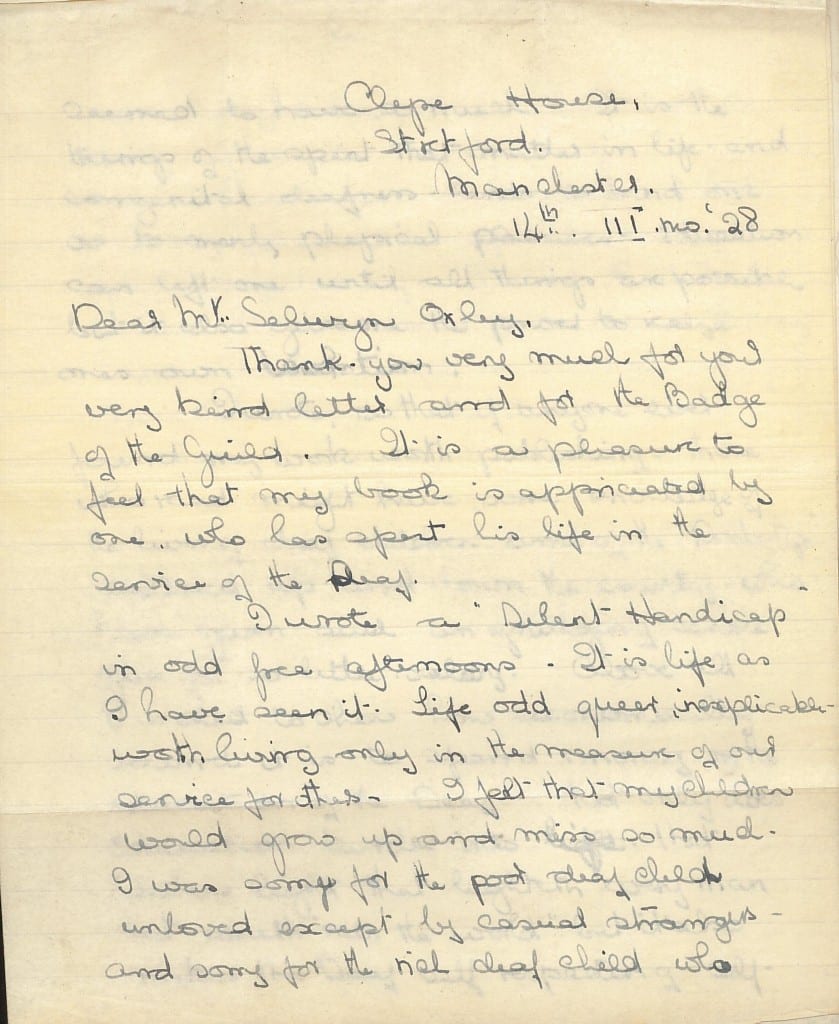

The letter, a follow up to a much longer letter signed by a number of notable people, appears in a scrap page from Ernest Ayliffe’s collection of various odd documents and letters, with associated cuttings, and the page is dated ‘Feb 22/29’. The year was 1929, the newspaper the Daily Mail.

Breeders of the Deaf

Sir,- For the past twenty-one years I have been advocating the sterilisation of those who are responsible for the perpetuation of a considerable section of our “deaf-mutes.” But hitherto such advocacy has fallen upon deaf ears.

There are numerous examples in our deaf schools all over the country of born deaf children whose disability is due to what is known as “true hereditary deafness,” a condition which, in its propagation, follows the Mendelian theory.

Dr. Kerr Love, of Glasgow, and I have published for years past a considerable amount of work upon this question, and have shown that, while there are hearing carriers of deafness whom it be difficult to sterilise, owing to the practical impossibility of recognising them until they produce deaf children, those who are born hereditarily deaf breed true, and can be safely expected to do so.These are the cases which require sterilisation, and I have a considerable number of family trees showing this sure method of perpetuation of deafness.

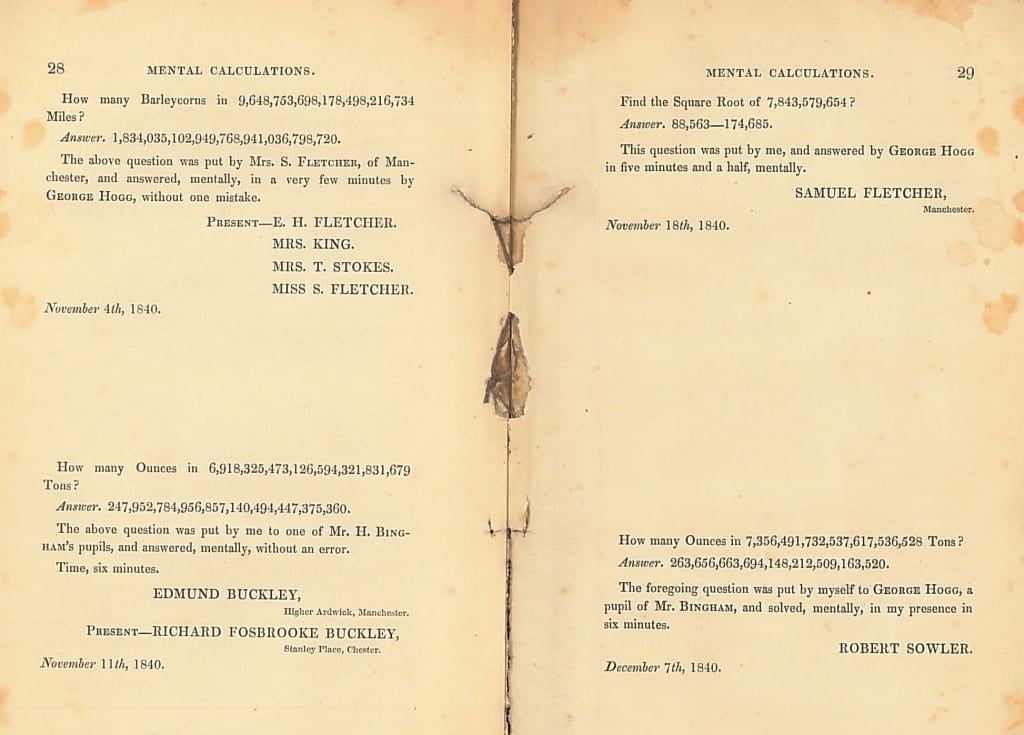

I need not expatiate upon the advantage to the race and to the State if this form of deafness could be eliminated, but I would point out that the education of a normal hearing child costs approximately £5 18s., while that of a deaf child is £69 18s. 10d.

This gives an additional reason for sterilisation of the unfit, and it is satisfactory to see that the letter published contains the names of bishops as well as of men of science.

MACLEOD YEARSLEY, F.R.C.S., F.R.A.I.

81 Wimpole street, W.1.

As you see, Ayliffe added some comments –

Comments

Wish to call attention to this very damaging letter to the cause of the Deaf.Whatever the merits of the system it is a brutal one.

May be justification for it in a few cases- but very few.

Why Deaf & Dumb! Why not blind. You get some cases to my certain knowledge – generations of them (in few cases likewise)

Why not M.Ds?

Why not the vicious?

Why not criminals?

[pencil] Difficulty of appeal [pencil]

Our appeal for the Deaf is very seriously jeopardised by such a letter.

Can anything be done by the committee to counteract it?

[pencil] Implications by quotation from Kerr Love

Ought we to repudiate the whole thing or let Yearsley get away with his self advertisement? [pencil]B.D.D.A. – [pencil] Indignation – but –

N.I.D.

Ayliffe’s comment there seems to expose Yearsley. His understanding of the new science of genetics does not seem to be great. Despite his other certain talents, in this letter he comes across as a shameless self-promotor, a mere shadow of his relative.

Percival Macleod Yearsley Lancet. 1951 May 19;1(6664):1130.

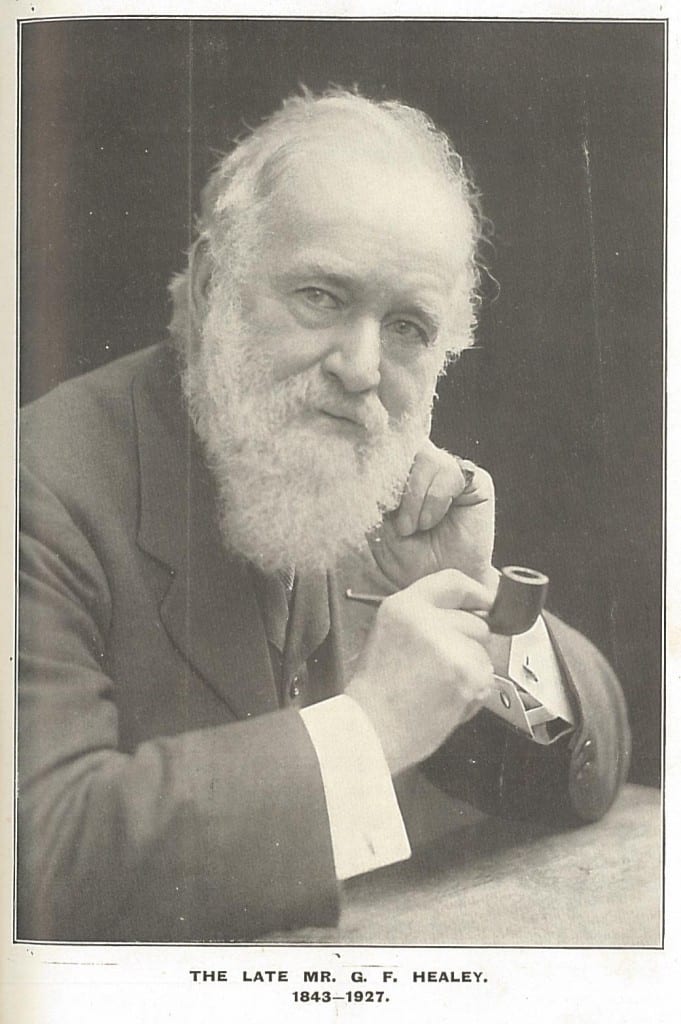

Updated 23/12/2016 with photograph of Yearsley from Teacher of the Deaf

Close

Close