A tragedy from 1906 with a modern resonance

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 15 July 2016

I came across a very short item in the British Deaf Times for October, 1906, p.225, which led me to discover more about a Lincolnshire family from over a century ago, and a tragic event.

Harriet Shaw was born in Grimsby in 1826/7, and christened on the 27th of February. According to various census returns she was born deaf. Her parents were Elizabeth, or ‘Betsey’, and William Shaw, who was a shipbuilder, neither being described as deaf on the census. In 1848 she married a Hull man, Robert Matthews, a ship’s carpenter who later became a shipwright like his father-in-law. They had at least six children, William Joseph, born in 1850, who became a boilermaker, Robert, a carpenter, born c. 1853, George, also trained as a carpenter, born c. 1856, Emma born c. 1860, Hannah born in c. 1864, and Elizabeth born in c. 1868. William, Hannah and Elizabeth, were all, like their mother, born deaf, according to the census returns. The 1861 census says that George was also deaf, but he is not described as deaf in the 1871 census. Clearly census returns are not infallible, relying on the information of informants who may not have been thorough in their admissions to the enumerator, and enumerators were also mistaken or careless on occasions. It is a great pity that we have few early reports from local deaf missions, and those we have for Hull, East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire are rather patchy. Local papers might tell us more, and there must have been an inquest. It seems very likely (I would stress without firm evidence) that in a family like this where mother and many children were deaf, that they would have signed.

William, the oldest child, never married. The tragedy is that, on the 6th of September 1906, his sister, probably the youngest sister Elizabeth who was still living at home with her brother, found him hanged in a workshop. One can only imagine what desperation, despair and disillusionment, led him to this, but the truth is that Deaf people are more vulnerable to isolation and mental health issues.

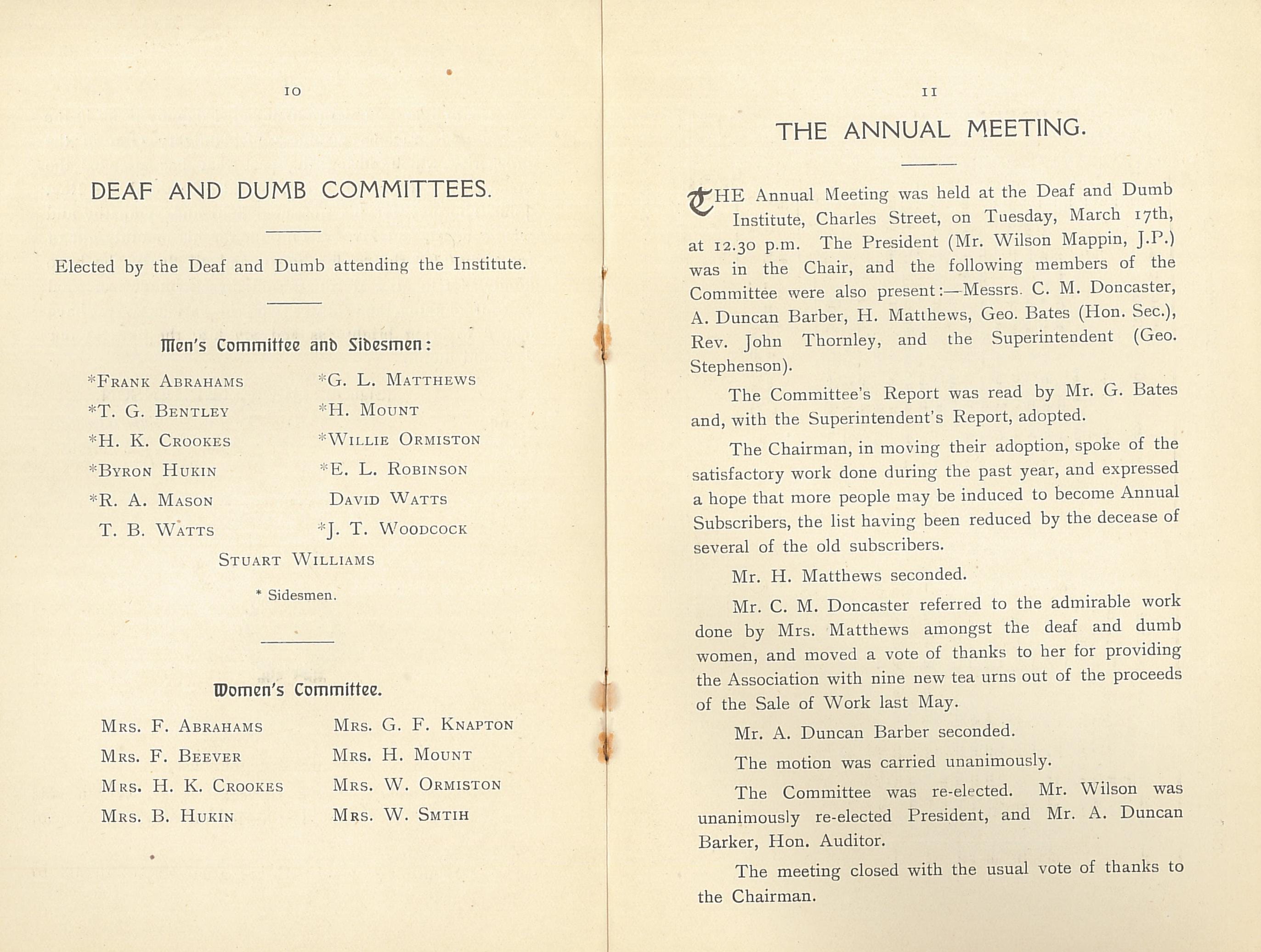

In 1882 Emma Matthews married a Deaf man from Sheffield, Thomas Gilley Bentley, an engraver, and they had at least one Deaf child, Victoria Maud Bentley, born in 1887. That is the third generation from Harriet Shaw. The 1911 census shows that the Bentleys had ten children, six surviving at that time. Victoria married Albert B Clarke in 1918. Albert, born c. 1889, was also Deaf from childhood. From the above annual report for Sheffield, we can see that Thomas Bentley was involved with the Sheffield Association in Aid if the Deaf and Dumb. Perhaps we have the sort of idea of ‘deaf ethnicity’ here in the Matthews/Shaw/Bentley/Clarke families – see Lane et. al for a discussion of this.

In 1882 Emma Matthews married a Deaf man from Sheffield, Thomas Gilley Bentley, an engraver, and they had at least one Deaf child, Victoria Maud Bentley, born in 1887. That is the third generation from Harriet Shaw. The 1911 census shows that the Bentleys had ten children, six surviving at that time. Victoria married Albert B Clarke in 1918. Albert, born c. 1889, was also Deaf from childhood. From the above annual report for Sheffield, we can see that Thomas Bentley was involved with the Sheffield Association in Aid if the Deaf and Dumb. Perhaps we have the sort of idea of ‘deaf ethnicity’ here in the Matthews/Shaw/Bentley/Clarke families – see Lane et. al for a discussion of this.

At that time George Stephenson was still working with the Association, which leads me to suggest that anyone interested in the history of Deaf people in the late 19th and early 20th century, may be interested to read Nick Waite’s new book, Alone in a Silent World, which covers this period and the long association of the Stephensons with the Sheffield Deaf community.

FURTHER INFORMATION

I have heard of a recent case which resonates with the story of William Matthews, although of course we know very little other than the outline of William’s story.

This open access article from 2007 is a review of the literature on Deaf people and Suicide up to that point – Suicide in deaf populations: a literature review. That article has been widely cited. This links to PubMed article abstracts using the search terms mental health and deaf. The British Society for Mental Health and Deafness (BSMHD) “focuses entirely on the promotion of the positive mental health of deaf people.” Additionally the Samaritans have an email contact jo@samaritans.org

Lane, H., Pillard, R.C. & Hedberg, U. The People of the Eye : Deaf Ethnicity and Ancestry. 2011

1851 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 2113; Folio: 202; Page: 13; GSU roll: 87742

1861 Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 2389; Folio: 55; Page: 15; GSU roll: 542964

1871 Census – Class: RG10; Piece: 3414; Folio: 63; Page: 22; GSU roll: 839406

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 3270; Folio: 36; Page: 24; GSU roll: 1341780

Hannah and Emma in the 1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 3815; Folio: 133; Page: 8; GSU roll: 6098925

William in the 1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 3089; Folio: 62; Page: 36

Albert in the 1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 4375; Folio: 57; Page: 26

Close

Close