Hon. Venetia Marjorie Mabel Baring, 1890-1937 – “Deafness and Happiness”

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 22 December 2017

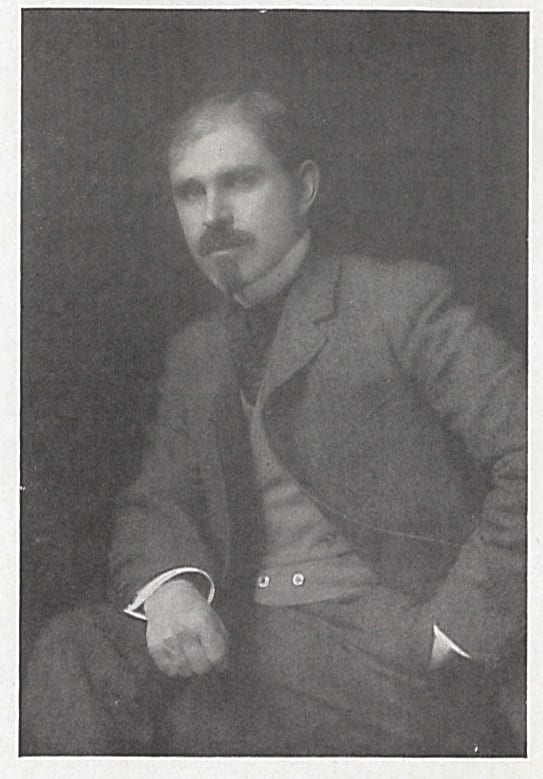

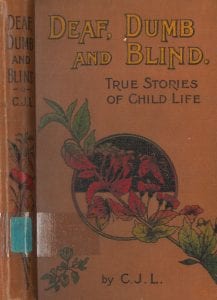

Venetia Marjorie Mabel Baring was a daughter of Francis Denzil Edward Baring, 5th Baron Ashburton. In 1930 she wrote a booklet Deafness and Happiness, our copy being the 1935 reprint. It was published by A.R. Mowbray, who produced religious and devotional books. It is on vey good quality paper. According to the short introduction by “A.F. Bishop of London” who seems to be Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, she was “afflicted in the heyday of her youth with almost total deafness” (p.iii). Her photographic portrait is in the National Portrai Gallery collection, and a drawing of her is in the Royal Collection.

Venetia Marjorie Mabel Baring was a daughter of Francis Denzil Edward Baring, 5th Baron Ashburton. In 1930 she wrote a booklet Deafness and Happiness, our copy being the 1935 reprint. It was published by A.R. Mowbray, who produced religious and devotional books. It is on vey good quality paper. According to the short introduction by “A.F. Bishop of London” who seems to be Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, she was “afflicted in the heyday of her youth with almost total deafness” (p.iii). Her photographic portrait is in the National Portrai Gallery collection, and a drawing of her is in the Royal Collection.

She was born in London in 1890. She wrote her book with the encouragement of Winnington-Ingram. Below is a page from the book which gives a flavour of its religious polemic. It is certainly of interest to anyone who is fascinated by attitudes to deafness and how they have or have not changed over the years.

It is certainly of interest to anyone who is fascinated by attitudes to deafness and how they have or have not changed over the years.

In 1936, Arthur Story wrote a letter to the BMJ about deafness. Venetia Baring wrote a respose, echoing his words and developing her own ideas about deafness:

The helplessness of medical science where deafness is concerned is incontestable, and, as it is not of itself a menace to life, research into causes has suffered on financial grounds in comparison with other diseases. The complete lack of official understanding of deafness was painfully illustrated in the great war, when it was necessary for a few public-spirited individuals like the late Sir Frederick Milner to fight for the rights of deafened ex-Service men. There are certainly signs that the medical profession is becoming increasingly alive to the fact that the monster is hydra-headed and that there are few mental and physical disorders to which it does not prove an open door unless intelligently handled.

From the last line of this letter we learn that she was “not born deaf, had acute hearing up to 19, and used no “aids” to nearly 30″ (ibid).

From the last line of this letter we learn that she was “not born deaf, had acute hearing up to 19, and used no “aids” to nearly 30″ (ibid).

She died aged only 47 on the 15th of July, 1937, having suffered from serious illness before then. Indeed, she added a chapter to the second edition of her book on ‘The Power and Use of Pain.’ “Science is working for the abolition of suffering; but it will never succeed, because, while sin exists, pain is inevitable and can even be a vital factor in the development of human personality.” (p.37) She was clearly someone who had experienced pain and tried to work her own way through it.

It would be interesting to find out more about her.

Baring, Venetia, The Deaf and the Blind Br Med J 1936; 1 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.3934.1134 (Published 30 May 1936)

Close

Close