In a passage about the Ulster Society for Promoting the Education of the Deaf, Dumb and Blind, I cam across this line – “one of the most fascinating writers of our day, […] who, having become deaf in her youth, is obliged to hold communications by means of an interpreter, – Charlotte Elizabeth, – a name known throughout the world” (Report of the Ulster Society for 1838, p.13). Since she seems to have faded from memory, I thought her a fitting subject. Charlotte Elizabeth Tonna, (nee Browne) was born in Norwich on 1st October 1790, where her High Tory father was a minor canon (ODNB). He mother was of Scottish covenenter descent, and with such parents she grew up inculcated with strongly anti-catholic views (Murphy 2005). A sickly child, she became deaf when aged 10, then threw herself into reading and literature. “Later in life she came to see this fascination as sinful because it served no useful, religious purpose, but her early reading in drama, poetry, and fiction provided excellent preparation for her future writing career.” (ibid) She influenced both Harriet Beecher Stowe and Elizabeth Gaskell.

She married Captain George Phelan and moved with him to Canada for two years, then to his estate in Kilkenny. He was abusive to her, and we are told this was a symptom of oncoming insanity. After he died she married a much younger man, the evangelical writer Lewis Hippolytus Joseph Tonna.

The complex and contradictory nature of her attitudes to the Irish is best illustrated by her relationship with John Britt, a deaf mute from Kilkenny. She regarded him as her adopted son and educated him and converted him to Protestantism, even alienating him from his own family. Yet ultimately, she treated him as a servant rather than as a child of her own. (Murphy)

Early in her book about Britt, The Happy Mute, she says,

in truth, every one of us is born dumb, and must remain so until reason dawns, and we begin to imitate the words used by others. But when a person is born deaf, he continues dumb because he hears no language spoken ; or, at best, he will only make strange noises, in attempting to imitate the movements that he observes in the lips of others, who can use their organs of speech. Thus are the poor mutes shut out from communicating their ideas, except by such signs as they can devise to express themselves by ; and these are seldom understood or regarded, unless by those very nearly and tenderly interested in the welfare and comfort of the afflicted creature who uses them. Of course, all moral instruction is confined to mere tokens of approval or displeasure, as the child’s conduct is correct or not ; and religious teaching seems to be out of the question, where words are wanting to convey it. We may teach a child who was born deaf, to kneel to hold up his hands, to move his lips, and often he will do so with the most affecting aspect of devotion ; but we can tell nothing of God the Creator and Preserver, the Redeemer and Sanctifier of our fallen race. (Elizabeth, 1841 p.9-10)

The collected Memoir of John Britt (1850), collated from various of her writings after her death, lays on the fiery evangelical terror with epistrophe –

Oh remember, reader that they have, as you, an evil heart of unbelief – that they are, like you, born in sin and conceived in iniquity, and that nothing but the blood, the all cleansing blood of Christ can sprinkle their consciences and make them clean. (ibid p.7)

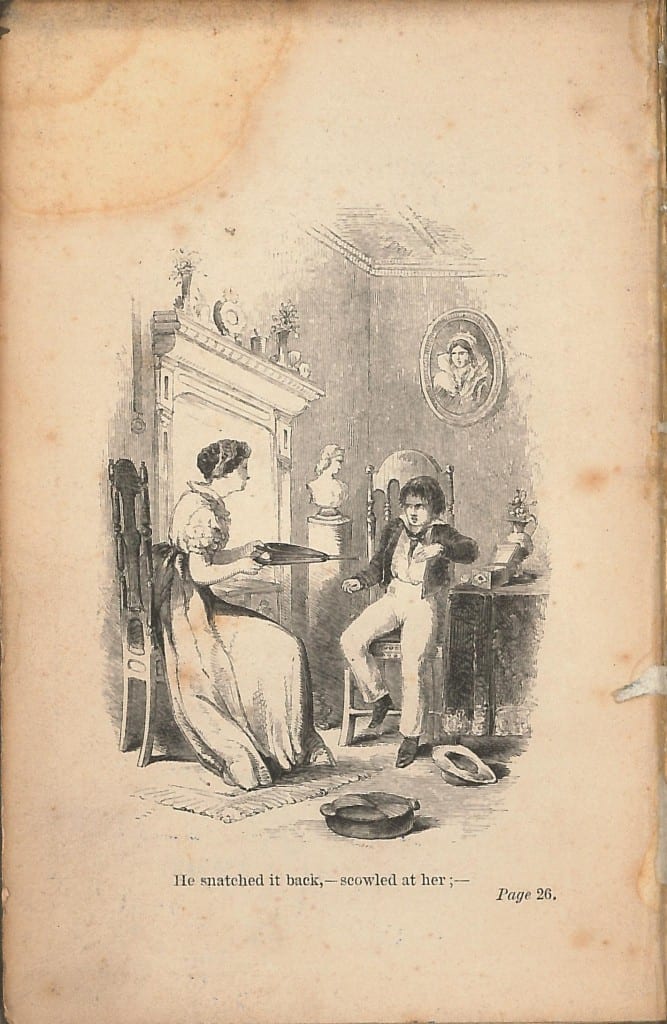

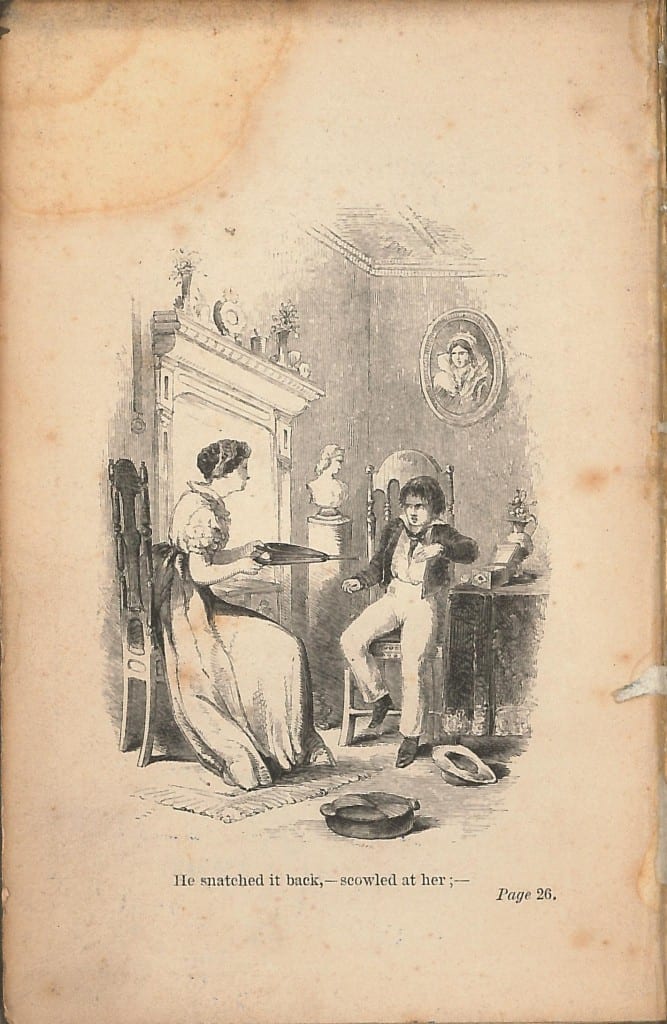

In 1823 in Kilkenny she came across a deaf boy called Sylvester, aged 12 to 13, but though he seemed to be intelligent, “he had no thought beyond his personal gratification, of which one part indeed, consisted in pleasing his friend” (p.9), but then in October he brought along ‘Jack’ (John), who made much better progress while Sylvester ceased to come to her. Large alphabet letters were used to teach him words like ‘dog’ and ‘man’, while the illustration shows how she tried to show him that there was a God by puffing bellows – he then said “God like wind! God like Wind!” (p.27).

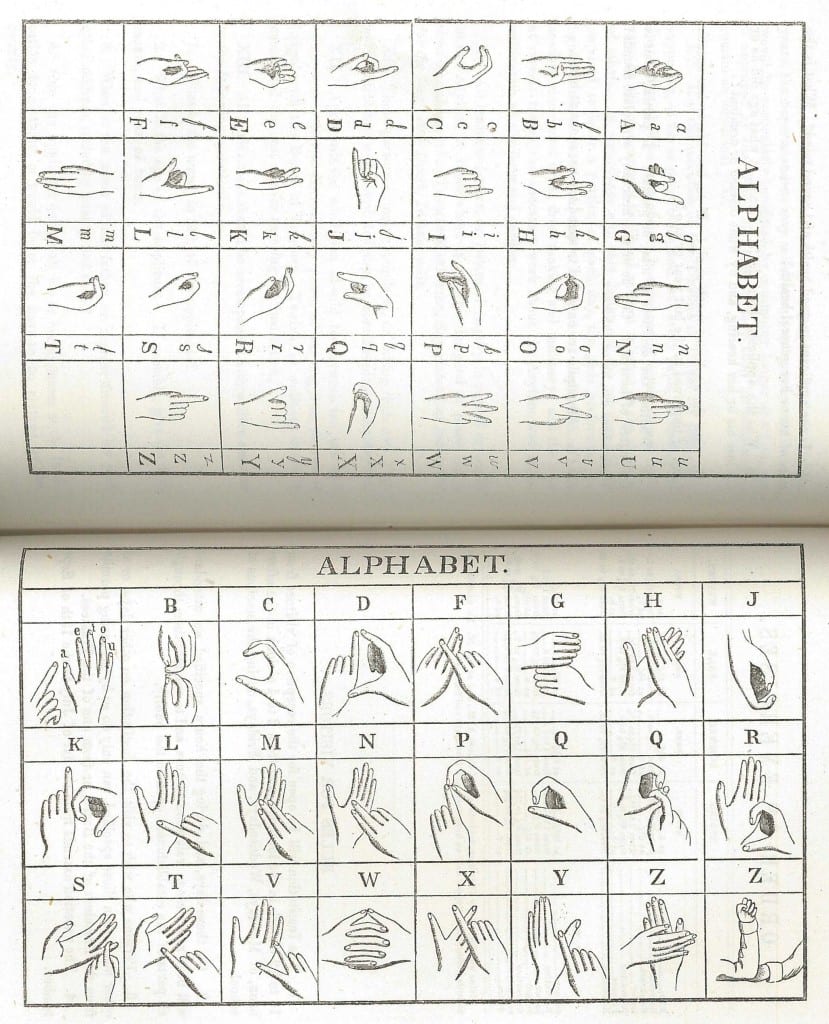

We learn from the Memoir of John Britt that Charlotte was expert at ‘Dactylology’ or finger spelling (p.13). One wonders if there was a little confusion and if the compiler was aware of the possibility that she was signing with people as well as finger-spelling. The aim of her education seems to have been to take him from a ‘natural’ Atheism through to a belief in God, and not the Popish God she so disliked – “Two things his soul abhorred – Satan and Popery” (Memoirs p.52). These were her prejudices, or perhaps rather genuinely held beliefs, that she was filling him with, that she had absorbed from her parents.

When she left Ireland, she took him with her, moving to Clifton with her brother for a time. John Britt died in 1831 of consumption after a long illness of over a year – “sometimes when greatly oppressed, leeches were applied, and once half a dozen were put on his side, at his own request”(Memoir p.124). The Happy Mute begins with the quotation in the title of this page, “a year and a half has scarcely passed since I saw him depart to be with Christ ; and often do I look back with thankful wonder on his short but happy life – his slow and painful, yet most joyful death ; and I look forward to the period when, through the blood of that saviour whom he so dearly loved, I hope to meet my precious charge in the mansions of glory” (p.7).

he was buried in Bagshot church-yard, near the Eastern window. It was a four miles’ walk through melting snow, under a drizzling rain, on a comfortless day, yet all the boys of the Sunday School, and a few of the girls, appeared, attired in their best, and formed in procession, following on foot the carriage which bore the dumb boy’s remains to their final resting place. (Memoirs p.137)

In 1844, “a schirrous induration appeared under the left axilla, which soon rapidly took a malignant form, and after being an open cancer for more than eighteen months, eventually caused her death by its attacking an artery, and causing exhaustion from loss of blood.” (Obituary p.434)

In 1844, “a schirrous induration appeared under the left axilla, which soon rapidly took a malignant form, and after being an open cancer for more than eighteen months, eventually caused her death by its attacking an artery, and causing exhaustion from loss of blood.” (Obituary p.434)

She died on the 12th of July 1846, “and about half an hour before her departure showed manifest signs of joy, although unable to speak, when he who tended her death-bed, spelled on his fingers the name of ‘Jack,’ and reminded him that she would soon meet him again.” (Memoir p.140)

The happy mute; or, The dumb child’s appeal. 8th ed. London, L. and G. Seeley, Dublin, William Curry, and Robertson, 1841.

Memoir of John Britt, the happy mute; compiled from the writings, letters, and conversation of Charlotte Elizabeth. 2nd ed. London, Seeleys, 1854.

Memoir of John Britt, the happy mute. 18–? Title page missing, information taken from front cover. (the two Memoirs are different slightly in pagination and it is possible I have used both editions in the quotations above)

Obituary in The Gentleman’s Magazine

David Murphy, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 94, No. 373 (Spring, 2005), pp. 105-107 Published by: Irish Province of the Society of Jesus Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30096012 Accessed: 24-04-2015 12:52 UTC

ODNB = Mary Lenard, ‘Tonna , Charlotte Elizabeth (1790–1846)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/27537, accessed 24 April 2015]

Filed under Deaf History, Deaf people, Deafness

Tags: religion

Comments Off on “his slow and painful, yet most joyful death” – Deaf Author Charlotte Elizabeth Tonna and John Britt ‘The Happy Mute’

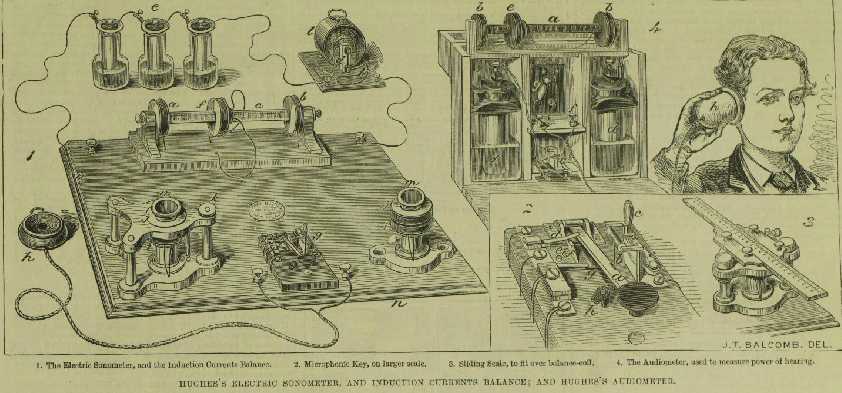

The description under “Curiosity” says it was drawn for The Boy’s Own Paper.

The description under “Curiosity” says it was drawn for The Boy’s Own Paper. Charles Webb Moore, Ephphatha 1933, p.

Charles Webb Moore, Ephphatha 1933, p. Close

Close