“we often took sweet counsel together” -Simeon Kutner, Headmaster of the Jewish Deaf School

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 16 October 2015

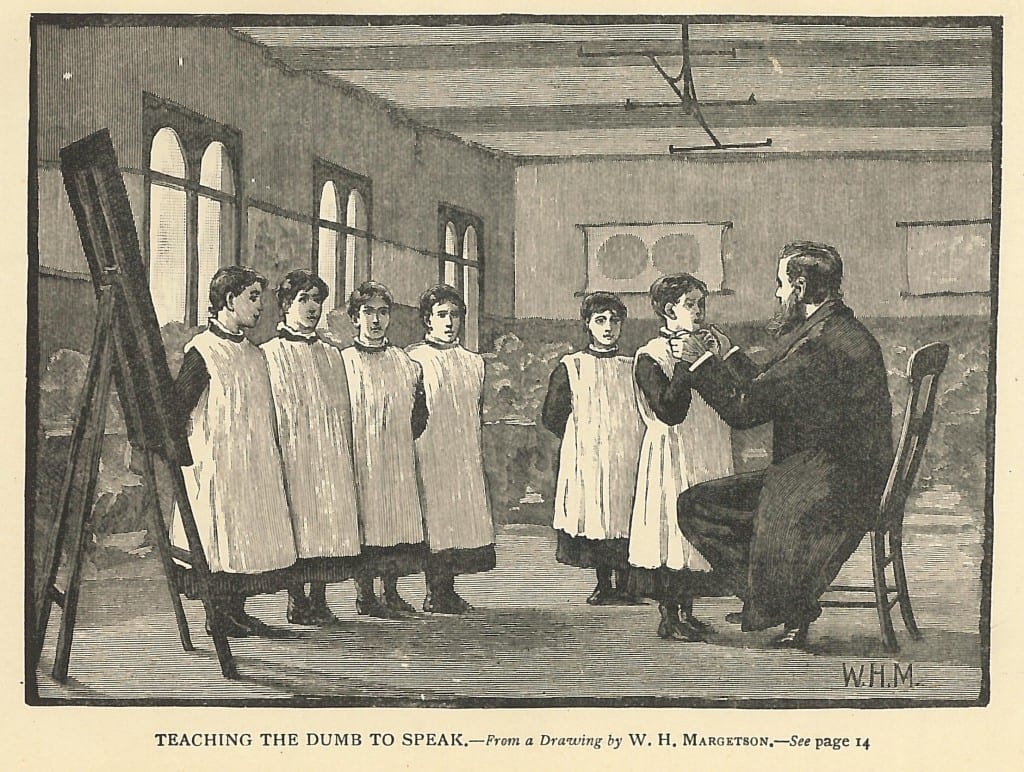

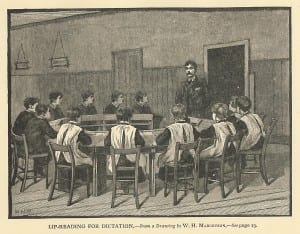

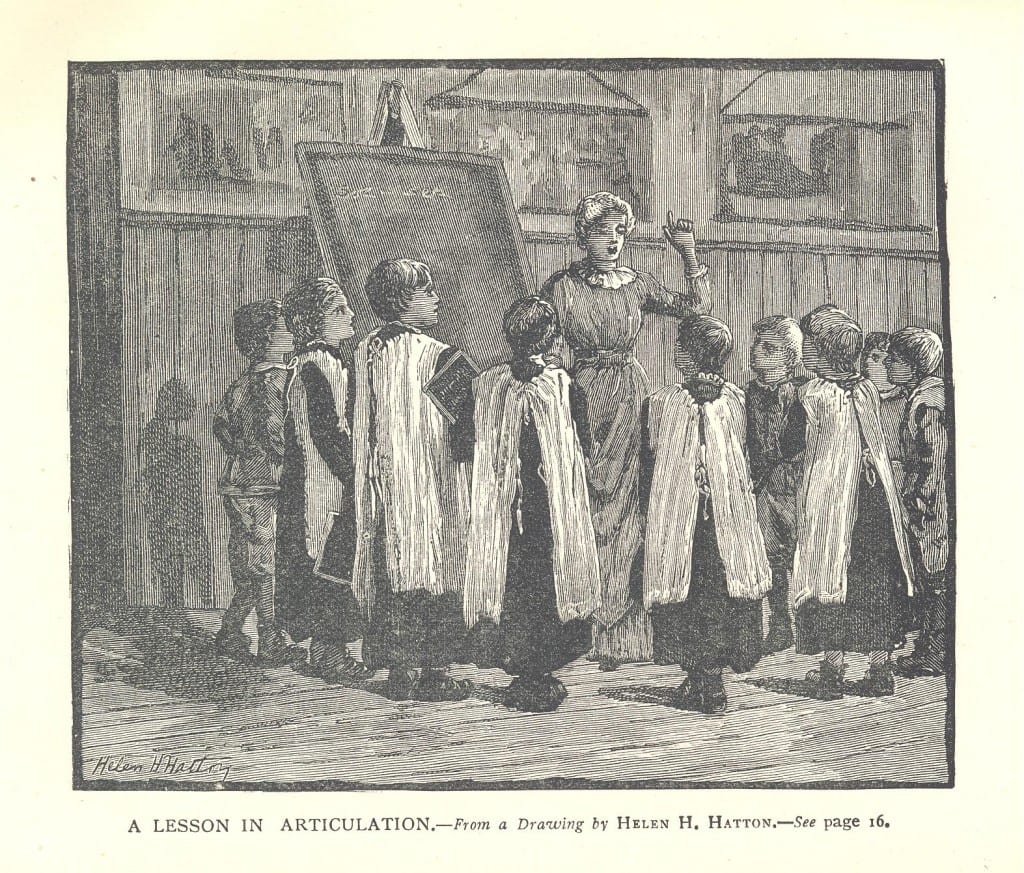

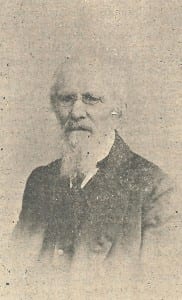

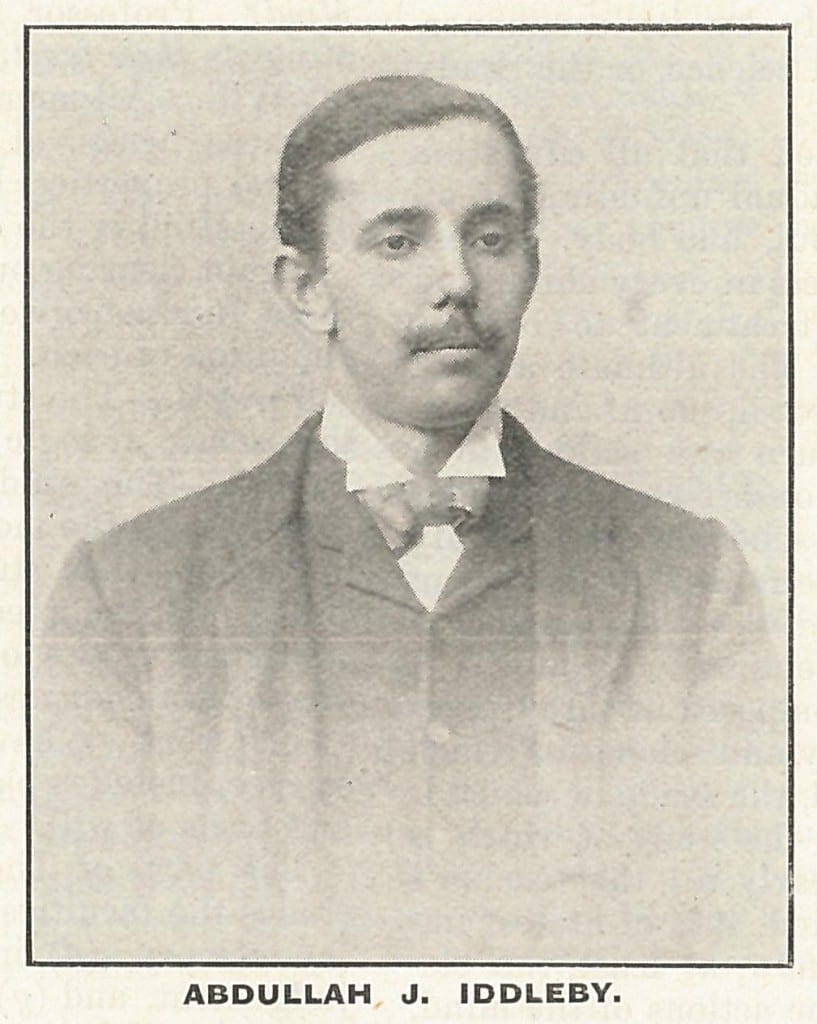

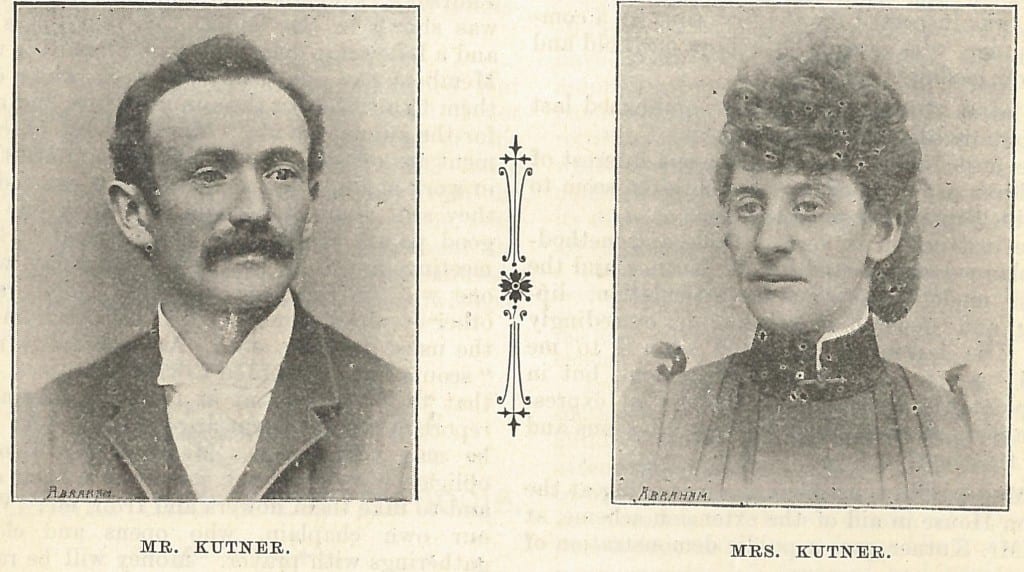

Simeon Kutner, (1861-1916) was an oralist teacher of the deaf, who became Head Master of the Jews’ Deaf and Dumb Home, Wandsworth. In 1894 he took over at the school from Mr. Simon Schöntheil of the Vienna Deaf School. Schöntheil had replaced van Praagh in 1872. There is a close link therefore between this school and the origins of the oral system in Germany.

Kutner was born in Poland, or rather Polish Russia. When he was approximately six years old the family emigrated to Great Britain, settling in London, in Southwark (see census 1871). His father was a hair dresser. From 1867 to 1874 he was a pupil at Borough Jewish School in south-east London (BDM 1897). He attended the Jews’ College, Finsbury Square intending to study theology, but after two years became instead a teacher of the deaf under Schöntheil. He remained there until 1882, having quite a wide number of duties in addition to teaching. He also studied drawing at Birkbeck, we are told by the BDM article (p.252).

The school was visited in June 1877 by a delegation from the first Conference of Headmasters (see extract in last blog), which included Andrew and Colville Patterson, Dr. Buxton, and the Rev. Stainer. The visit convinced Andrew Patterson to try oralism at the Old Trafford Institute. It seems that this was a way into Manchester for Kutner, as he was appointed to teach there with the oral method in 1882. He remained at the school there until July 1894, taking on additional teaching duties and becoming head master of the Evening Continuation Schools for the Deaf and Dumb in 1891. That same year he married Blema Wood and had four children (ibid).

He went on several holidays with his good friend Fred Gilby.

I had, however, one very understanding, close friend among the oralists in Simeon Kutner, the Principal of the Jews School for the deaf. Even from his Notting Hill days he had been a dear friend of mine, and we often took sweet counsel together. He attended more than one service or function at St. Saviour’s to see what we did – and approved. We once spent a fortnight together, cycling from Hammersmith to Camberley, going by train that evening to Southampton, crossing to Havre and bicycling onwards together through Normandy, sleeping at such places as Caudebec, Lisieux, Avreux, St. Lo, Coutances, Granville, and Jersey. At the last place he was with us at a little gathering of deaf people where I had been asked to preach. The pathos of the little scene overcame him, and he wept. For this I loved him all the more. His companionship was a privilege. Uplifting – educated – yes,it was even religious; he was full of sweet charity, good humour and refinement. We were able to kneel down at the same time at night and we both used the Lord’s Prayer with some depth of sympathy, yet he was a Jew. There are many Christians I know with whom I have not been able to converse as well as I could with him on matters spiritual. (Gilby Memoirs, p.148-9)

Kutner was also on the Executive of the College for Teachers of the Deaf and Dumb, Paddington Green.

He had at least one serious breakdown in health, and recovered, but died in 1916 having undergone an operation.

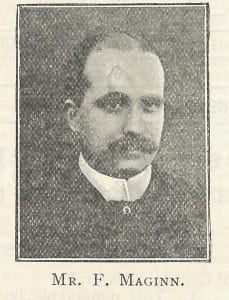

The Jews’ Deaf and Dumb Home and its Head Master. British Deaf Monthly, 1897, 6, 252-54. (photo)

The Jews’ Deaf and Dumb Home and its Head Master. British Deaf Monthly, 1897, 6, 252-54. (photo)

Death of Mr. Kutner, Ephphatha 1916 no.31 p.445

Gilby’s unpublished Memoirs

1871 Census: Class: RG10; Piece: 595; Folio: 92; Page: 15; GSU roll: 818904

Close

Close