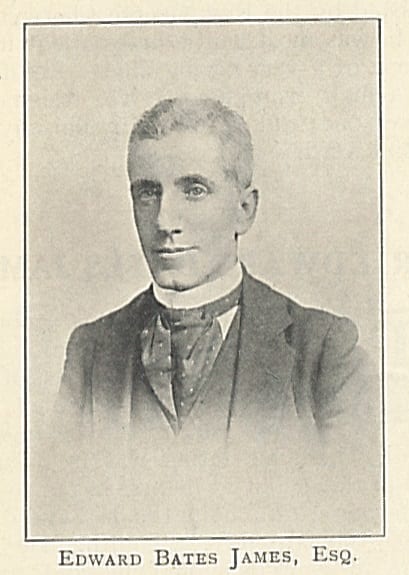

“he used to interpret in court cases” – Edward Bates James (1863-1936)

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 2 June 2017

Edward Bates James was born in the Commercial Road, East London, on March the 5th, 1863. His mother, Isabella Dorothea Bartlet, born in 1839, was a pupil at the Old Kent Rd School – you can see her named there in the 1851 census as Bartlett. His father Edward Francis James (b.1826) was in business, having once been a servant, but although not mentioned by Gilby in his memoir, the 1881 census says he was sexton at St. Saviour’s Church when he and Edward were living at 272 Oxford Street. His parents had married in 1862. His mother was an upholstress in 1861, when she was living with her widowed mother at 150 Tottenham Court Rd – approximately where the Cafe Nero is opposite Sainsbury’s.

He did mission work in his spare time, from the age of 13 helping the Rev. Samuel Smith. His obituary says that,

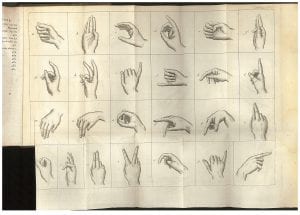

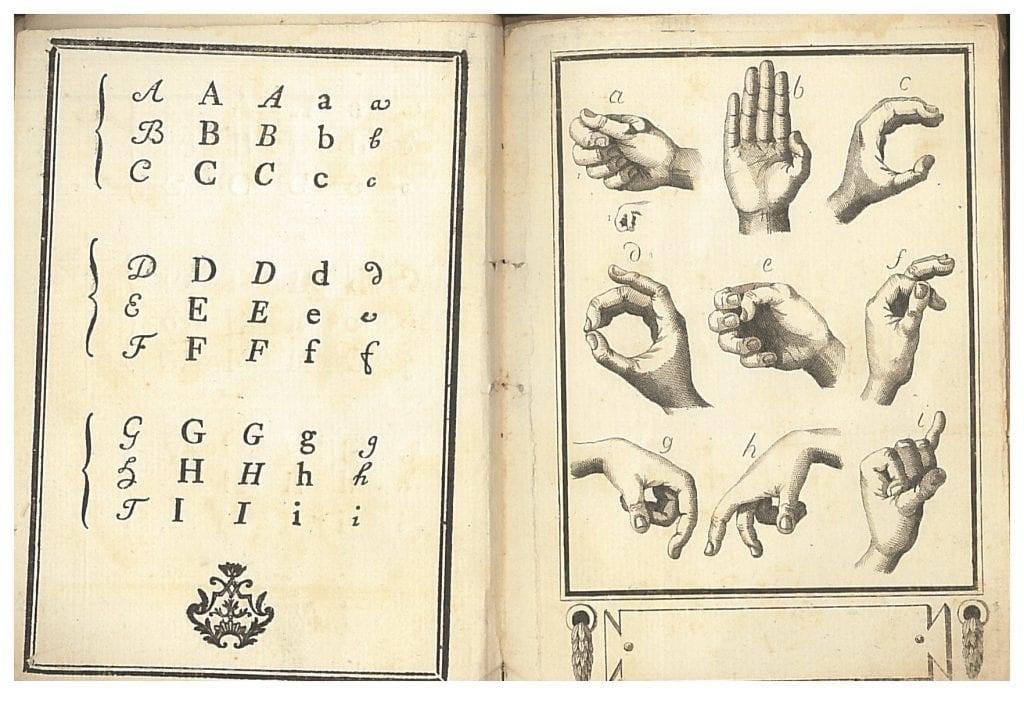

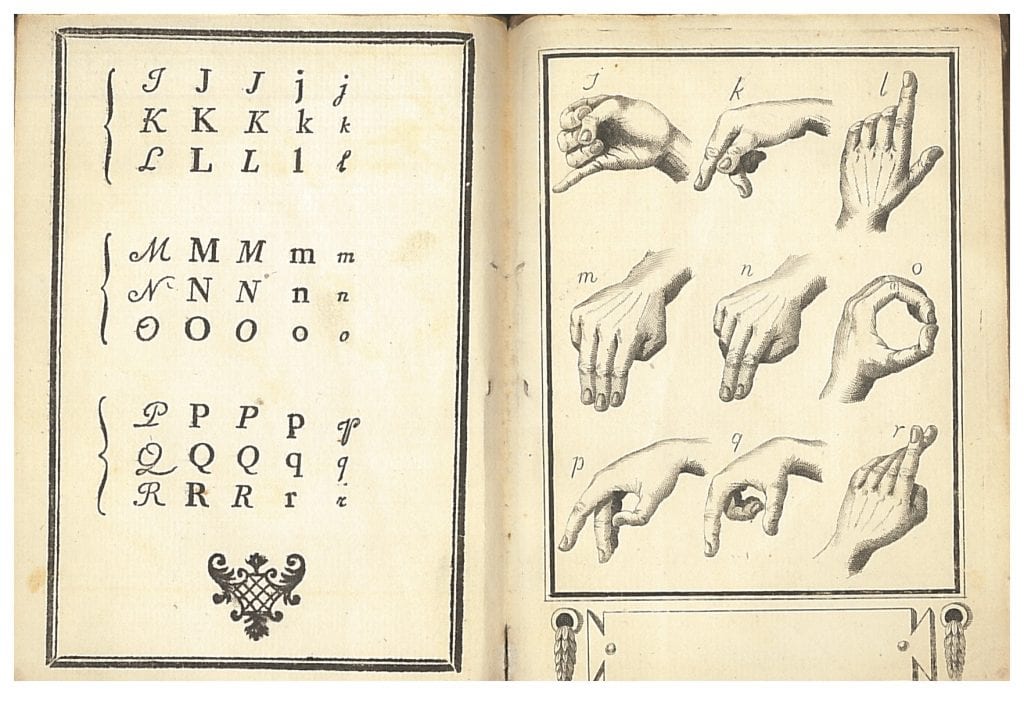

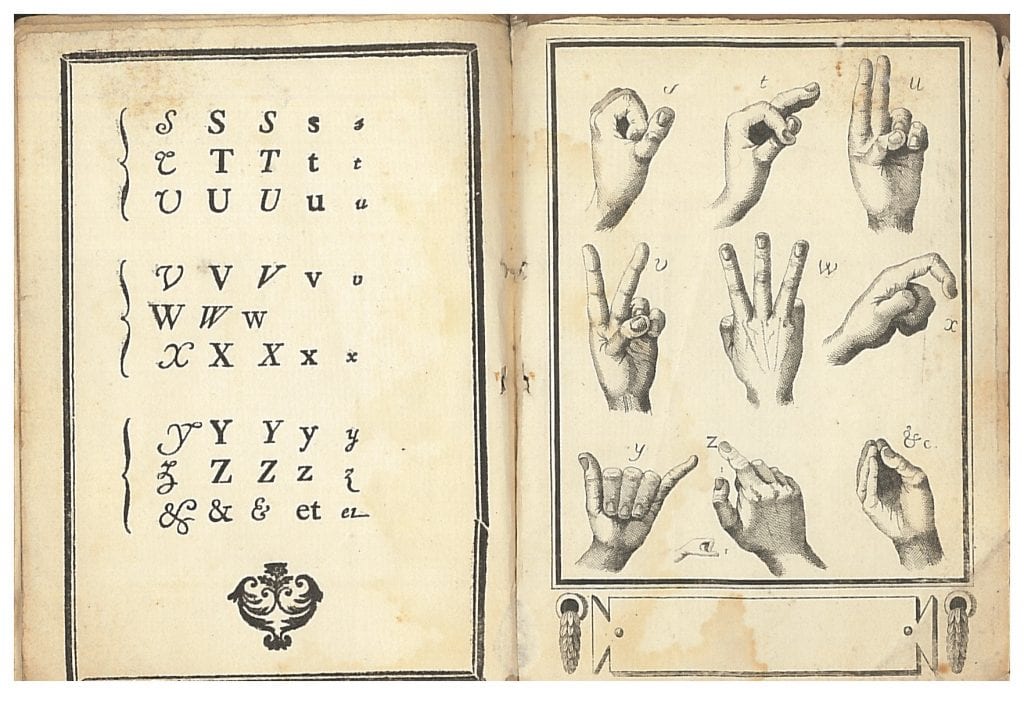

Owing to the fact that his mother was deaf and dumb, he used to accompany her to all meetings at the old Polytechnic in Regent Street, the last Mission Centre in London before St. Saviuor’s was built. There he used to meet those, early in London history of deaf work, who were active in the religious and social welfare of the Deaf, especially Samuuel North and the Rev. Samuel Smith, and the latter was a frequent visitor at his parent’s’ home. When quite young he used to interpret in court cases, and assist in the missions (Ephphatha, 1936, p.1849).

Later on he became a teacher of the deaf, training with William Neill at the Northern Counties School for the Deaf in Newcastle. The Ephphatha article tells us he regarded Neill with a mixture of “awe and admiration,” and he would never forget the “good caning of half a dozen big fellows late at night for some wrongdoing,” administered by Mr Neill (p.297). The article does not tell us when he left, but at some point he returned to London on the death of his mother. He worked, we are told, “in the City in the day, spent a good deal of his time in deaf work, and saw St. Peter’s School, Islington, first opened for them” (ibid). I have never heard of that school – was it a proper school or only a Sunday school? He also carried on services at Morley Hall in the absence of Jane Groom. His ‘City’ work would have been as an accountant or accountant’s clerk, according to census returns.

Marrying in 1889, his wife Ellen bore two children but died after only three years of marriage, on their wedding anniversary, which meant he had to withdraw from some of his mission work to look after his sons. One of his sons was Walter Melville James – perhaps named after Alexander Melville? His other son was Alfred. His wife, Ellen James, who was ten years older than him, was like his father was born in Kettering, which suggests she was perhaps a cousin – I have not had time to conform this.

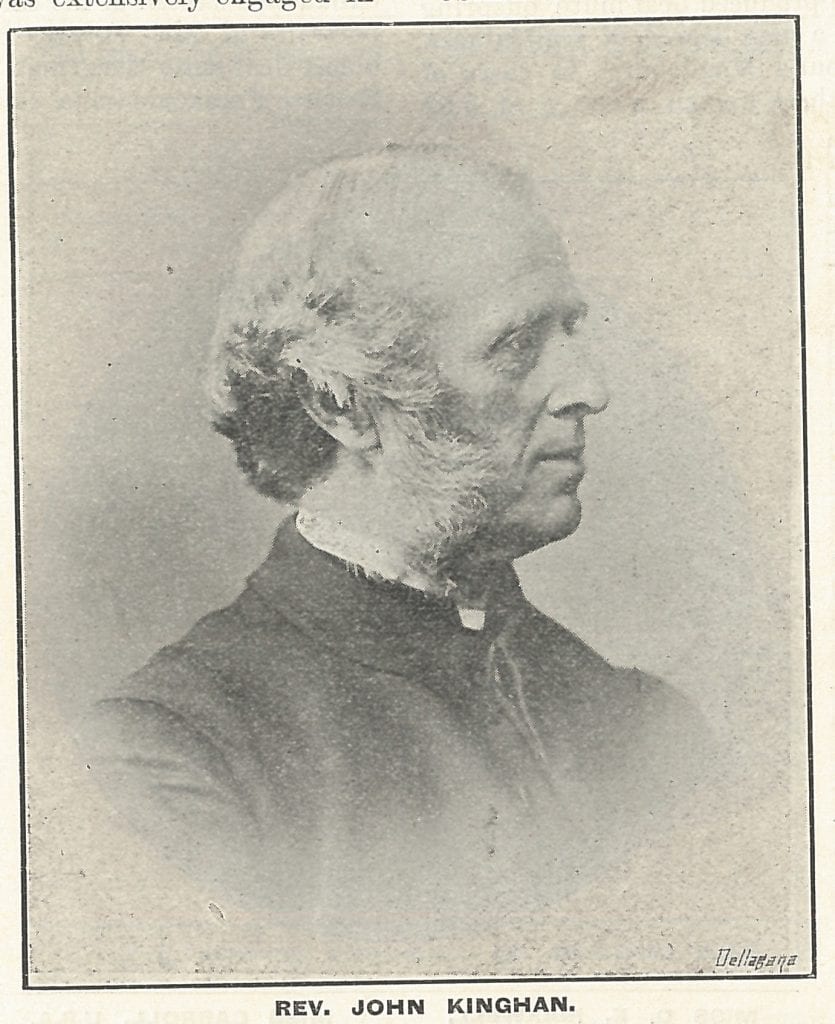

After meeting old friends at the 1905 Bazaar that Gilby organized at the Grand Central Hotel*, his desire to work with the Deaf community was re-kindled, and he joined the R.A.D.D. on the 1st of February, 1906, becoming ‘Parochial Reader’ of St. Mark’s, North Audley Street, near where he had been a pupil at a school (ibid p.298). He helped fill in when R.A.D.D. missioner John P. Gloyn‘s health was failing –

in the matter of success in finding work for the deaf he has probably had no equal; and the friendliness and suffering, perhaps in many cases not well skilled, have had great cause to bless him for opportunities afforded them of getting their living. His heart has always disposed him to help again and again those who truly do not deserve it – and who, under his superintendence, have become self-supporting and something like industrious people. His has truly been a work of rescuing the perishing, and though often disheartened by the downright wickedness and perversity of some of his cases, he has never turned back or entirely despaired. On leaving North London recently to become the right-hand man of the Chaplain at St. Saviour’s, he was presented with a gold chain and illuminated address containing signatures by old friends who valued his earnest and helpful ministrations and admired his faithful devotion to duty.

He seems to have taken on a lot of Gilby’s work when he was ill during the Great War. He died on Sunday, the 9th of February, 1936. Gilby only mentions him in passing, saying of him, ‘more anon,’ but only then mentions seeing him before going to South Africa in 1934. They may well have been acquainted since childhood. He was buried in Brookwood cemetery, Woking.

*The obituary says 1905, but Gilby’s memoir says 1904. there were however several bazaars around that time.

Edward Bates James, Ephphatha, 1914, No.22 p.297-8

Edward Bates James, the Great Missionary and Friend of the Deaf, Ephphatha, 1936, April June, No. 109 p.1849-50

The Late Mr. Edward Bates James, British Deaf Times, 1936, Vol.33 p.34

Census 1861 – Class: RG 9; Piece: 102; Folio: 131; Page: 24; GSU roll: 542574

Census 1881 – Class: RG11; Piece: 92; Folio: 57; Page: 31; GSU roll: 1341021

Census 1901 – Class: RG13; Piece: 1257; Folio: 30; Page: 6

Census 1911 – Class: RG14; Piece: 7385; Schedule Number: 245

Close

Close