Giulio Ferreri (1860 or 1862-1942)* was an oralist teacher of the deaf who was Rector of the Royal National Institution, Milan, for many years. He travelled fairly widely it seems, visiting America, where he studied the educational methods, writing a monograph in 1903 that was translated for the Volta Bureau in 1908 as The American Institutions for the Education of the Deaf. According to the scribbled note in the front of that book, he met Selwyn Oxley on two occasions, in Milan in 1924**, and at the Teacher Conference in London in 1925.

Not long after the appearance of Ferreri’s American publication, the French psychologist Alfred Binet and his colleague Théodore Simon, who together created the first IQ test, wrote an article in l’Année psychologique reprinted and translated later in The American Annals of the Deaf, ‘An Investigation Concerning the Value of the Oral Method.’ They found that congenitally deaf people who were considered to be oral successes, were unable to communicate effectively orally:

when one is a bit of a psychologist, one feels curious to know how an art so delicate as that of speech can be taught to unfortunate beings who are totally deaf. Is it possible that speech, with its delicate shades of intonation which we acquire through the ear, can be learned by individuals who have never heard? Is it possible? Perhaps it will be thought that no one has the right to declare anything impossible; but this is one of those things which require a very strong proof to be accepted. (p.35)

[…]

we refrain from concluding that the oral method is a total failure. We do not like such positive assertions; the truth has more delicate shades of distinction. If the oral method really presented no sort of advantage whatever, it would not have held its ground in our schools for thirty years. But we believe that its practical value has been overestimated. It seems to us to be a sort of pedagogy de luxe, which produces moral effects rather than useful and tangible results. It does not enable deaf-mutes to get situations; it does not permit them to enter into relations with strangers; it does not allow them even a consecutive conversation with their relatives; and deaf-mutes who have not learned to speak earn their living just as easily as those who have acquired this semblance of speech. That is the observation which we made again and again, and with a persistency which seemed to us very eloquent. (p.44)

Ferreri was not impressed, responding with what Moores (1997) points out as a very personal attack:

Alfred Binet and his fellow helper, Dr. Simon, have made an investigation as to the value of the oral method, and have published a report of it in their well-known review, l’Année psychologique. In the minds of the authors the results of their investigations must have appeared very important, but to educators of the deaf, as well as to every conscientious scientist, it is a very poor affair. But in that case, it may be asked, is it worthwhile to take this study into serious consideration? It is; because one must apply to the crime of Alfred Binet and Co. the theory of Licurgus, who taught that one should judge a misdeed not in itself but in its consequences. And. in view of the wide circulation and the merits of l’Année psychologique, the mistakes made by the Paris psychologists in judging of the oral method may be disastrous in their consequences upon the opinions of learned men. (p.46)

[…]

In regard to the capacity of criticism, which Mr. Binet denies to the educators of the deaf, we can only reply: Inform yourself of what has been written and discussed concerning the methods of teaching and the means of their application during the past thirty years, and you will make a discovery, viz., that the teachers of the deaf understand very well the deficiencies of their work, and that their knowledge and their desires have always found an obstacle in that economic question which, if it is explicable in politicians and public authorities, is shameful in scientists and takes away all value from their investigations. And this is exactly what has happened to the investigations of Binet and Co. (p.48)

From disparate sources, including The American Annals of the Deaf, I have pieced together something of Ferreri’s life. He became an ‘instructor’ to the deaf in 1879. Depending on when he was born then – and one Italian page says 1862 rather than 1860 – he would have been between 16 and 19. In 1886 he was appointed Vice Director of the Royal Pendola Institute in Siena, and in 1892 he became editor of L’Educazione dei Sordomuti. The American Annals of the Deaf calls him “one of the most voluminous as well as one of the ablest writers on the education of the deaf in Italy” (1901). They add a note, in the brief notice of of the Catalogo Cronologico degli Scritti del Prof. Giulio Ferreri sull’ Educazione dei Sordomuti, (Siena, 1901), that as his future address is “Corso Castelfidardo 9, Turin, we infer that he is no longer connected with the Siena Institution, but we hope he is not permanently removed from the profession.” It seems then that visited England and America in 1901/2, presumably on leave from Siena, for in January 1902 he was at 1760 Q Street, Washington, when his article ‘Another word about the battle of methods’ appeared in The American Annals of the Deaf, (Vol. 47, p.30-44) before moving on to spend time in Palermo and Rome. In 1908 he was appointed to head the newly united teaching college and school in Milan.

Despite his ardent oralism, it seems there were dissenting voices in Italy. The 1904 World’s Congress of the Deaf in St. Louis, Missouri, had two short letters from Italian teachers read out, by G. Gioda of the Turin Society of Deaf Mutes and Francesco Guerra of Naples. The former said “For the exclusive use of the oral method, preferred by some teachers, the deaf have no use, but by the manual method an individual may receive a complete education” (Proceedings of the World’s Congress of the Deaf, 1904, p.131), while the latter said,

If you, dear comrades, have at heart the sorrowful lot in which thousands and thousands of unhappy deaf people live, especially the deaf of this fair Italy, whose lot is most hard, sad and miserable, vote an order of the day in favor of the combined system and in condemnation of the oralist imposters and charlatans who have wronged and exploited us long enough. […] I pray that the International Congress of the Deaf at St. Louis may signalize , if not our complete victory, at least an important step in our progress, the prelude and beginning of our approaching emancipation. In the glorious and beneficent name of De l’Epee I greet you fraternally, crying: Down with the imposters; down with the oralist charlatans; down with the exploiters! Long live De l’Epee; long live the honored Gallaudet, long live the Combined system! (ibid. p.130)

Unfortunately for them, it seems that the state stuck with Ferreri and his pure oralism. In 1907 he was at the International Congress on the Education of the Deaf in Edinburgh, where he presented this paper The Present State of the Education of the Deaf in Italy (Proceedings of the International Congress on the Education of the Deaf in Edinburgh, 1907, p.41-6). In 1925 he attended the Sixth International Conference on the Education of the Deaf, held in Margate, presenting a paper on ‘National Control of the Education of the Deaf and Dumb’ (International Conference on the Education of the Deaf, 1925, p.65-69). Later in the conference, he said

I am the oldest teacher, and I do not think that I should have come here. In my opinion the old teachers must be tired. They have nothing more to say, nothing more to teach, and it is necessary to have a young teacher. In the hands of the young teacher lies the future. (ibid, p.210)

I think that Ferreri seems to be forgotten as an international figure, unless someone can add some additional sources of information. The quotation from Guerra above is very interesting, and his choice of words, ‘deaf emancipation,’ seems to foreshadow the deaf liberation movement of the 1960s to 1980s. Someone might like to research this area further.

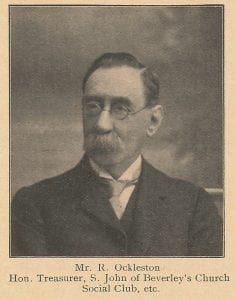

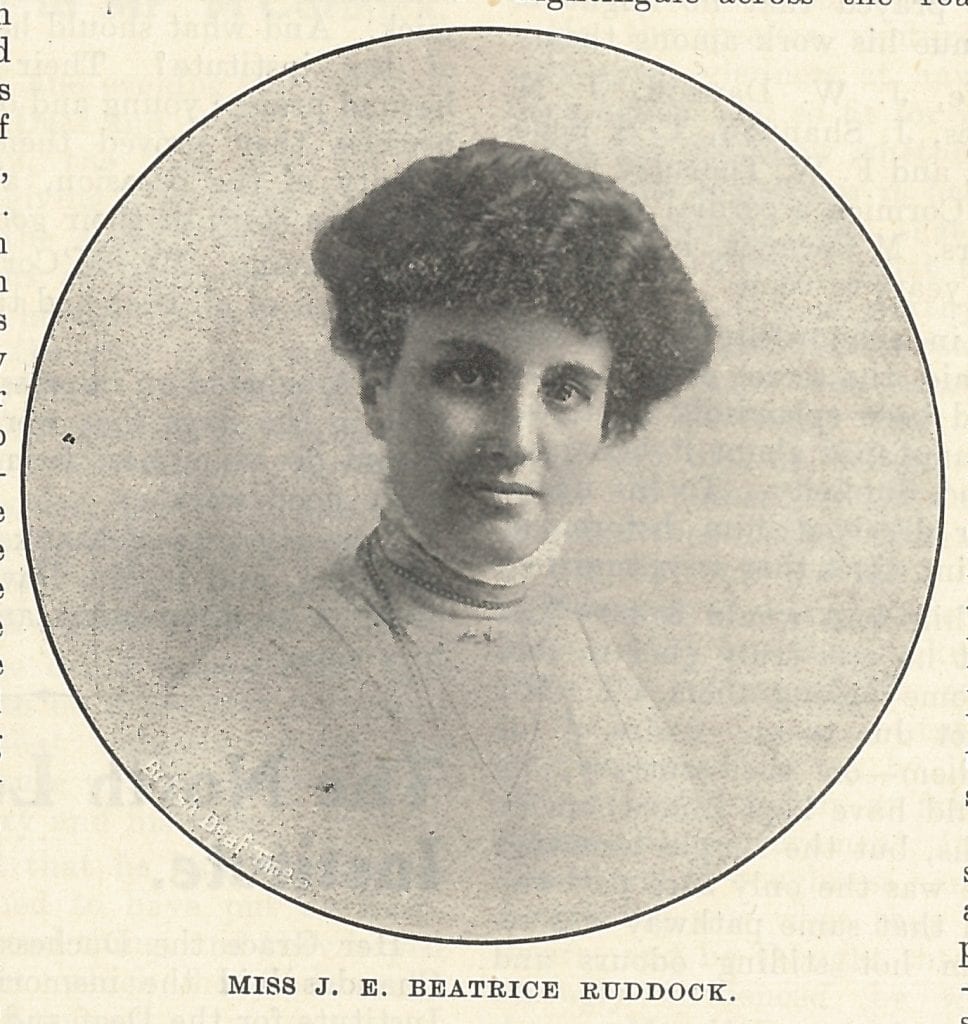

The above signed photograph is inserted into the front of Oxley’s copy of the book.

He was made an honorary doctor by Gallaudet College at the same time as Selwyn Oxley.

The American Annals of the Deaf, 1901, Vol. 46, p.544

Translated by the author from l’Educazione dei Sordormuti for October 1909. Ferreri, G. 1910. Mistaken investigations concerning the value of the oral method. American Annals of the Deaf, 55(1), 34-38 [Reprinted in American Annals of the Deaf, Volume 142, Number 3, July 1997, pp. 46-48]

Alfred Binet, Théodore Simon American Annals of the Deaf, Volume 142, Number 3, July 1997, pp. 35-45

Moores, Donald F., American Annals of the Deaf, Volume 142, Number 3, July 1997, pp. xvi-xx

*https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5dgzAQAAIAAJ&q=%22giulio+ferreri%22&dq=%22giulio+ferreri%22&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y

**The writing might suggest 1914 but this seems wrong

I have not at present any information on Ferreri’s personal life – if I have we will update this. He is I think the same as this Professor Giulio Ferreri who married an American lady, Ellen Charlotte Alexander, in London in 1901, but I understand that Ferreri is a common name in Italy, being the name for a ‘farrier’ – smith, so it is possible that is another Ferreri also from Milan. My Italian colleague has searched for him in vain on the web.

EDITED with additional information on 27th & 28th Feb 2017

You may wonder what happened to the archive material from Margate School when it closed. I cannot give a full answer as I do not know exactly what Margate had in the way of records, but broadly as far as I am aware the school and pupil records went to the Kent County Archives in Maidstone, while I believe that a full set of annual reports, and perhaps some other material, went to the British Deaf History Archive in Warrington. I suppose that they are both in the process of organising and cataloguing that material. What we took was only a few boxes of books that we are sorting through to fill any gaps in our collection. Most of these we already had, and unless you are an expert in the area of the history of education these are mainly rather dull and dry books!

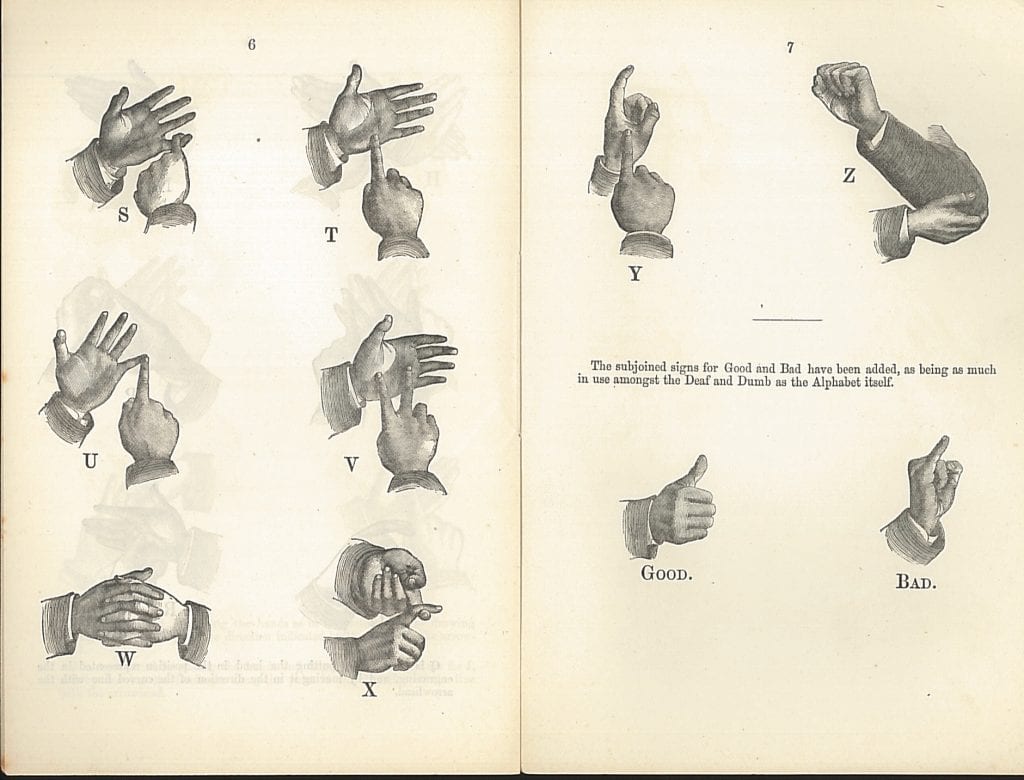

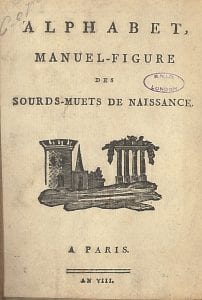

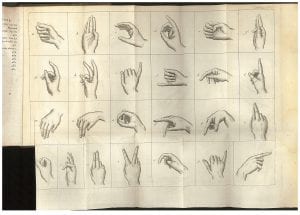

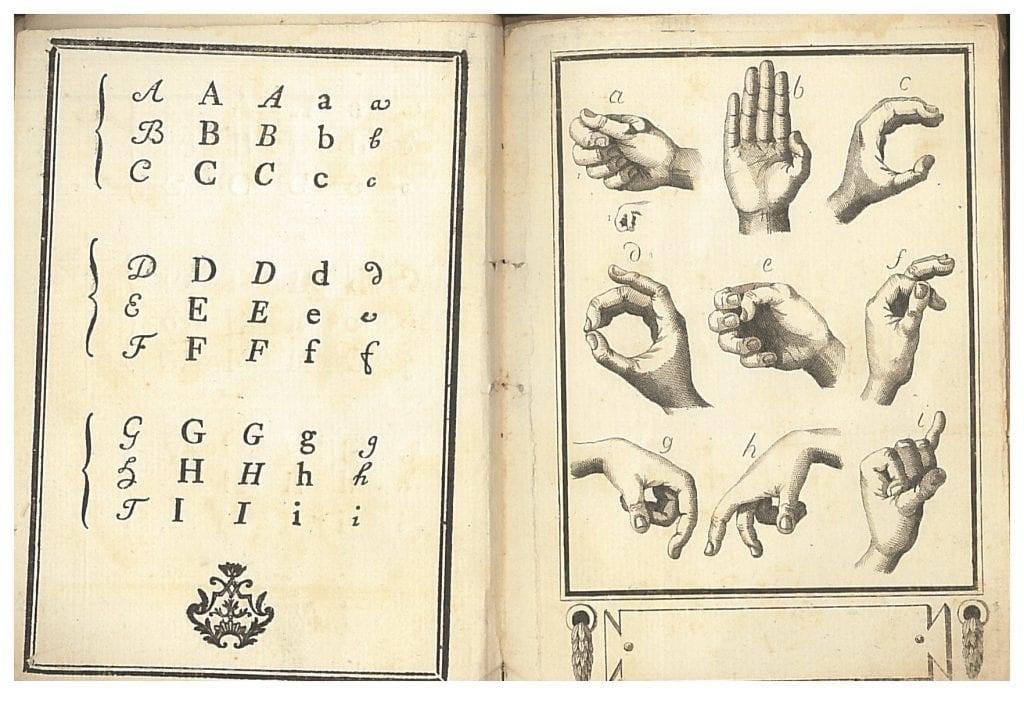

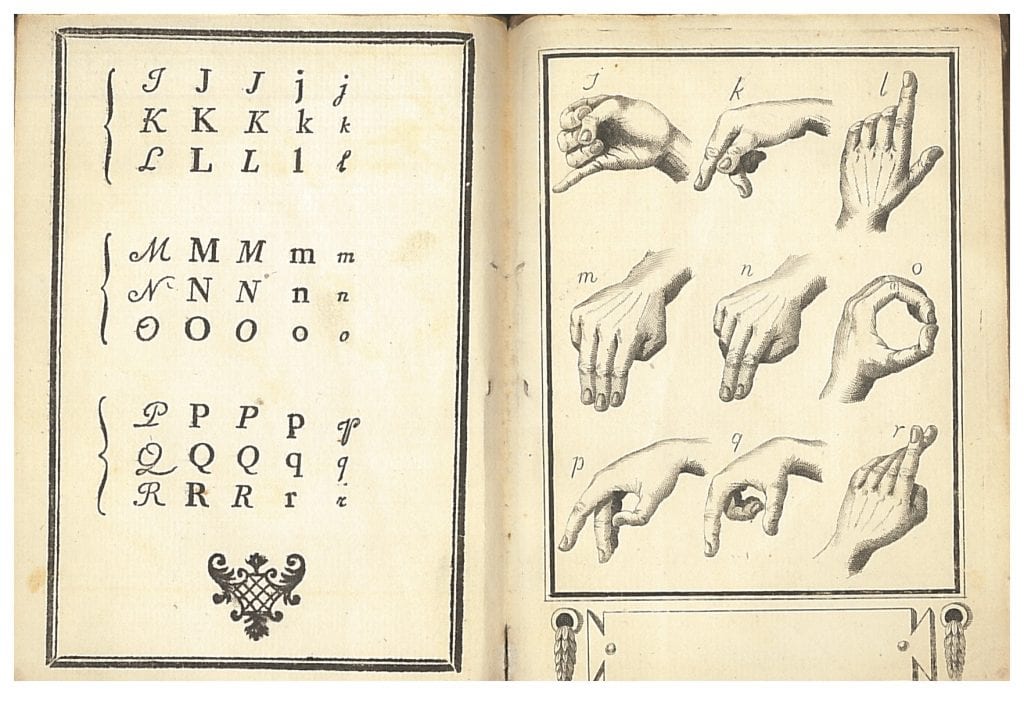

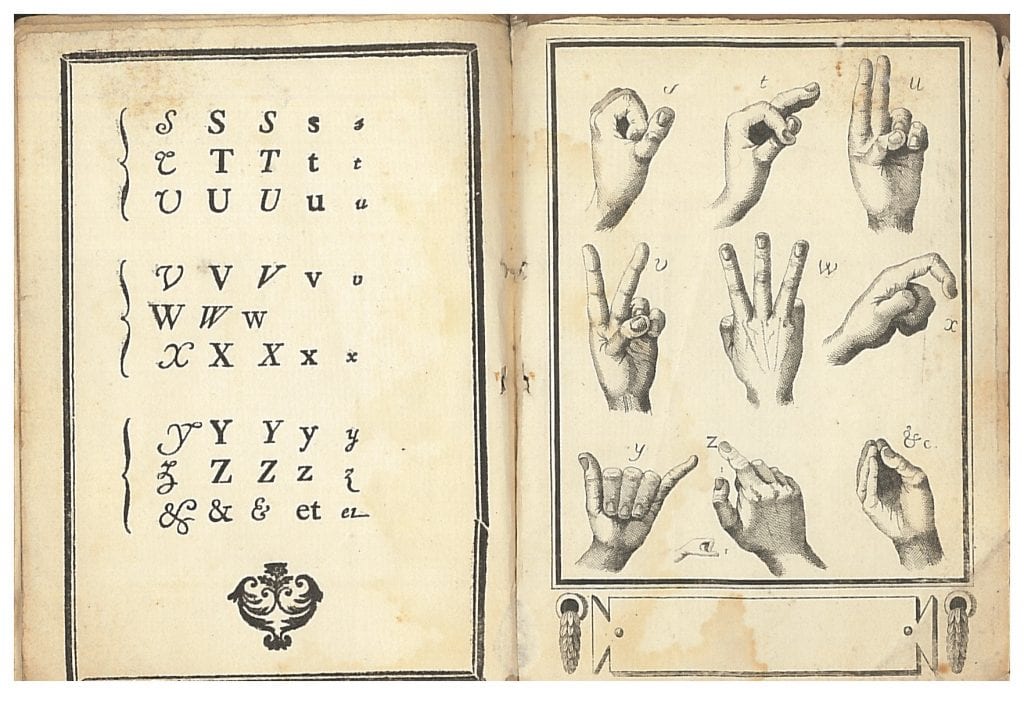

You may wonder what happened to the archive material from Margate School when it closed. I cannot give a full answer as I do not know exactly what Margate had in the way of records, but broadly as far as I am aware the school and pupil records went to the Kent County Archives in Maidstone, while I believe that a full set of annual reports, and perhaps some other material, went to the British Deaf History Archive in Warrington. I suppose that they are both in the process of organising and cataloguing that material. What we took was only a few boxes of books that we are sorting through to fill any gaps in our collection. Most of these we already had, and unless you are an expert in the area of the history of education these are mainly rather dull and dry books! There are a couple of gems however. This beautifully produced booklet, A Manual Alphabet for the Deaf and Dumb, […] sold at the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, Old Kent Road… came to us from the Margate School. I am a little surprised that we have not got it, though it is possible we have a copy – it is all a question of how it is described in the catalogue, so it could already be lurking in the collection. In the past the librarians used brown card and stapled many smaller loose items, of what we call ‘grey literature,’ into these covers. Grey literature can cover a multitude of things – but it would usually mean something that was not a book or a journal, or a report. It could be a reprint of an article, a booklet, a single page, and so on. I suppose they were doing what they thought was right, protecting the items and making them available for general use. We would not do this now – rather, we would put these leaflets or booklets in a box.

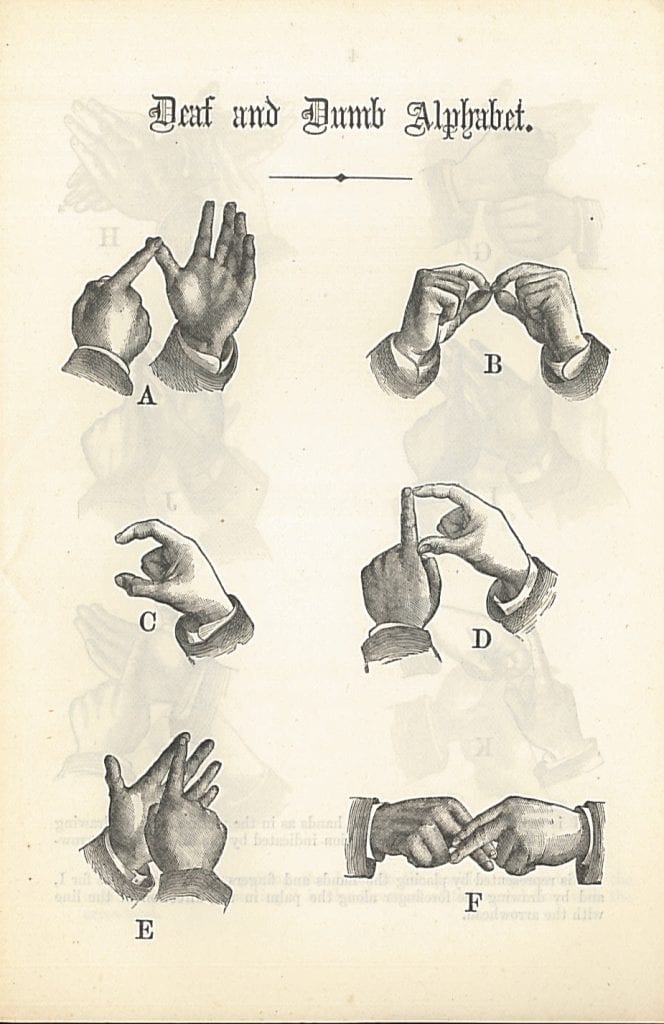

There are a couple of gems however. This beautifully produced booklet, A Manual Alphabet for the Deaf and Dumb, […] sold at the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, Old Kent Road… came to us from the Margate School. I am a little surprised that we have not got it, though it is possible we have a copy – it is all a question of how it is described in the catalogue, so it could already be lurking in the collection. In the past the librarians used brown card and stapled many smaller loose items, of what we call ‘grey literature,’ into these covers. Grey literature can cover a multitude of things – but it would usually mean something that was not a book or a journal, or a report. It could be a reprint of an article, a booklet, a single page, and so on. I suppose they were doing what they thought was right, protecting the items and making them available for general use. We would not do this now – rather, we would put these leaflets or booklets in a box. Note the way ‘Q’ is signed.

Note the way ‘Q’ is signed. Close

Close