Finding some more older documents that I thought might be of interest, and lacking time for anything more original, we supply the following ‘chronology’ of Deaf history. It may be that there are better versions of this elsewhere, and there are no sources given in the form of articles or books, but this might be a starting point for research. For example, I have no idea what the evidence is for the first statement. If I had to guess I would say this dates from the early 60s, perhaps 1964. I hope to revisit this page to update its ‘note’ style and add some supporting information where possible, though I will leave it where it ends in the 60s.

1. First legal bases for education of deaf person during Jewish and Roman Times.

2. Beginnings of modern education in Spain; Ponce de Leon (1520-1584), Bonet and his book in 1620.

3. Development of two basic and apparently conflicting educational philosophies for deaf children established in Europe; de l’Epee (1712-1789) with sign language, and Heinicke (1729-1790) with oral education, in Paris and Leipzig respectively.

4. British work: Bulwer and his books “Chirologia” (1644) & “Philocophus” (1648) Wallis and Holder as first teachers, but not without considerable acrimony between them. Braidwood and his family with their school, first in Edinburgh, then in London at Hackney, being the first organised program set up for deaf children. First public deaf “asylum” at Bermondsey by Watson, nephew of Braidwood (1792).

5. Growth of “asylums”: acceptance of fee paying of “parlour” pupils, proper medical attention, free meals, children admitted as early as 7 or 8 years onwards, but many at 13 or more, charitable background.

6. Scott in 1844 wrote “The deaf and dumb, their position in society, and their principles of their education considered.” Great emphasis on early parental training.

7. Donaldson’s Hospital opened in Edinburgh, 1850, with equal intake of hearing and deaf pupils of both sexes.

8. First nursery school in world for deaf infants set up in Great Britain at Manchester 1860. Ceased in 1884 because of need to provide additional space for education of older deaf children.

9. Development of missions for deaf adults. Glasgow 1827, Edinburgh 1835, Manchester 1850, others mostly in north of England in industrial areas. In 1840 deaf adults in London set up a deaf church which in time became the R.A.A.D.D. (Rooyal Association in Aid of the Deaf and Dumb). A free interchange of teachers and missioners became possible because of the frequent use of manual modes of communication in schools, thus first principal of Manchester nursery school formerly was Superintendent of Manchester Mission. Missions at Derby and Preston responsible for formation of schools there in 1875’s and 1890’s respectively.

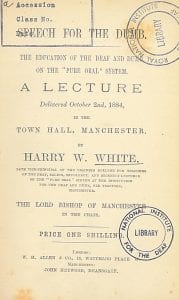

10. Milan Congress of 1880 – the 2nd International Conference of Teachers of the Deaf where very important resolutions affecting the “oral” education of deaf children were passed.

11. The Royal Commission of 1886-89 on the Blind, the Deaf, etc.

12. Development of “oral” v. “manual” controversy, first among teachers. It spread to missioners when the original hopes of “oral” supporters were not always successful. The introduction of examination requirements by the Association for the Oral Instruction of the Deaf & Dumb 1872; the Society for Training Teachers of the Deaf and for the diffusion of the German System 1877; the College of Teachers of the Deaf and Dumb 1885. These diplomas were not recognised by the Board of Education till 1909, and then only after the three bodies came together in 1908 to form the “Joint Examination Board for Teachers of the Deaf” with a single diploma.

13. National Association of Teachers of the Deaf formed in 1895 as professional body and started Teacher of the Deaf in 1902 as its organ. The National College of Teachers of the Deaf formed in 1918 by merging the National Association of Teachers of the Deaf into the College of Teachers of the Deaf. The Scottish Department of Education has however never recognised the College’s Diploma.

14. Formation of British Deaf and Dumb Association in 1890 to protest against the absence of deaf witnesses at Royal Commission. It sent a petition to the King in 1902 with 2,671 signatures asking for the combined system of education.

15. Legislation: First educational work was financed by Poor Laws – money raised from local rates, from 1834 onwards. Compulsory education was enforcable for hearing children in 1876. Compulsory education for deaf children in Scotland with “Education of Blind and Deaf Mute Children (Scotland) Act” 1890, and in England with the “Elementary Education (Blind and Deaf Children) Act” 1893. In the English Act, a deaf child was educated from its 7th to 16th birthday while a hearing child was educated from its 5th to 10th birthday (extended to 12 in 1900, and to 14 in 1921). Age for deaf child lowered to 5th birthday in 1937. Permissive to educate as from 2nd birthday from 1920 onwards, and provision made for higher education in the 1902 Act but these clauses very seldom used.

16. Preparation for life in the community: The N.I.D. undertook inquiry for on the “Industrial conditions of the deaf and dumb.” There were unsatisfactory findings despite the establishment of trade schools in Manchester in 1905 for boys and in 1923 for girls. Eichholz prepared “A Study of the Deaf 1930-32.” Clark and Crowden for the N.I D. and Department of Industrial Psychology prepared a survey on “Employment for the deaf in the United Kingdom” in 1939. The results of all these surveys were considered very disturbing.

17. Donaldson’s Hospital ceased unusual Neducation scheme in 1938. From 1850 to 1938, a total of 3,185 children of whom 1,403 deaf, were educated there.

18. Awareness of the value of residual hearing (when present): efforts by physicians in the 18th C. to cure deafness. Work of surgeons in the 19th C. to treat deafness but necessarily restricted to outer and middle ears. Work of Itard in Paris, and Urbanschitsch in Vienna who in early 1890’s developed methodical hearing exercises. The collaboration of medical man and headmaster at Glasgow Institution in 1890 where Dr. Kerr Love found less than 10% pupils totally deaf, and over 25% heard loud speech. Establishment of partially deaf classes from 1908 onwards. The development of electrical and radio engineering in early 20th C. but application restricted to use in classroom only (cumbersome and inefficient equipment).

19. Medical Research Council set up in 1926 to supervise research On physiology of hearing. In addition to other work, M.R.C. encouraged the team work of the Ewings and T.S. Littler in the Department of Education of Deaf in Manchester (founded 1920). The M.R.C. opened a clinic there in 1934 for the “study and relief of deafness.” By 1935 use of group hearing aids was recommended for children in schools for deaf.

20. Strained relations between teachers and doctors on educational policies for children with defective hearing, especially between 1910 and 1925.

21. Committee of Inquiry into problems of “medical, educational and social aspects of… children suffering from defects not amounting to total deafness” Report published in 1938 and contained educational classification with Grades I, IIa, IIb, and III which are still used by certain authorities although essentially outdated.

22. Outbreak of hostilities in 1939 between various countries caused the cessation of work on deaf problems, apart from preliminary research in readiness for development of the MEDRESCO hearing aid for the new National Health Service (1948).

23. Considerable postwar legislative changes affecting the deaf person. See Table A.

24. Various important postwar reports on educational, psychological and social aspects of deaf person in United Kingdom. See Table B.

25. Great multiplicity of organisations involved specifically with the deaf person in Great Britain. See Table C.

26. Development of research units on problems of deafness:

(a) The Otological Research Unit, National Hospital for Nervous Diseases, London under Dr. Hallpike,

(b) The Wernher Research Unit on Deafness, King’s College Hospital Medical School London under Dr. T.S. Littler which ceased in 1965,

(c) Audiology Unit, Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital, London under the late Miss Edith Whetnall F.R.C.S.

(d) The Audiology Unit, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading under Dr. K.P. Murphy.

In addition, there was research at the Department of Audiology and Education of the Deaf in Manchester.

27. Development of new categories of workers with deaf people. In addition to traditional three categories of doctors, teachers and welfare workers, now there were psychologists, medical officers, audiology technicians, speech therapists, health visitors and school supervisors with special courses on deafness for each of them.

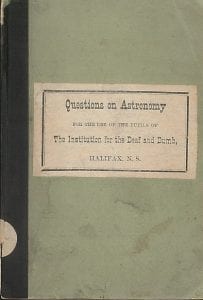

28. Development of electrical apparatus for hearing and speech, either as individual or group hearing aids or as visual aids. Scanty British literature on education of deaf children, particularly on development of language. A new training centre for teachers of deaf children opened in London in 1965.

29. Modification of educational philosophies in Great Britain. Before the Second War, the emphasis was on “oral” techniques with a strong minority for “manual” techniques and a gradual realisation of value of “aural”techniques. After the Second War there was a shift of emphasis from “oral techniques” to “aural techniques” in most schools or units. A minority group now asked for “combined” rather than “manual” techniques, and becoming more vocal. The B.D.D.A. sent a petition in 1954 with 5,000 signatures for the “combined” techniques to the Ministry of Education. Increasing awareness of special problems of the small group of very deaf children, especially if with additional handicaps. Weaknesses in present “oral” and “aural” techniques was more openly admitted.

30. Persisting attitudes towards the deaf person. Use of the term “deaf and dumb.” The term “dumb” is synonymous with “not so quick on uptake” or mental deficiency in the U.S.A. and that usage was brought over to Great Britain. Defective speech and limited vocabulary aggravated the situation. For the term “hard of hearing,” no precise definition is possible. The introduction of the terms “Deaf” and “Partially Hearing” categories of deaf child, but the prevalent tendency for members of the public still to call them “deaf and dumb.” See Table D

31. Present trends to watch: Units attached to ordinary schools, decline in residential schools, absence of vocational training or guidance in schools, greater emphasis on electrical amplifying apparatus for use at school or at home, ambiguity in educational and social status of “Partially hearing” pupil in community, the continued lack of closer co-operation between organisations or workers with or for the deaf person.

TABLE A

POSTWAR LEGISLATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE DEAF PERSON

(a) Disabled Persons (Employment) Acts, 1944 & 1958.

(b) Education Act, 1944.

(c) National Health Service Act, 1946.

(d) National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act, 1946.

(e) Employment and Training Act, 1948.

(f) National Assistance Act, 1948.

TABLE B

SELECT LIST OF PUDLICATIONS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE EDUCATIONAL, PSYCHOLOGICAL OR SOCIAL ASPECTS OF THE DEAF PERSON.

(a) 1945 Voluntary Organisations for the welfare of the deaf (IN Voluntary social services (their place in the modern state) Edited by Bourdillon, Methuen, London, 1945). This chapter written by J.D. Evans.

(b) 1950 Pupils who are defective in hearing, HMSO, Edinburgh.

(c) 1954 The training and supply of teachers of handicapped pupils, HMSO, London

(d) 1956 The Piercy Report, HMSO, London.

(e) 1957 Care of the deaf, by J.B. Perry Robinson for the Deaf Children’s Society, London.

(f) 1958 The deaf school leaver in Northern England, by R.R. Drewry, mimeographed, Nuffield Foundation.

(g) 1959 The Younghusband Report, HMSO, London.

(h) 1960 Certain social and psychological difficulties facing the deaf person in the English community, by Pierre Gorman, Ph.D. Thesis Cambridge University. 1963 A report on a survey of deaf children who have been transferred from special schools or units to ordinary schools, HMSO, London. Also Annual Reports of the Department of Education and Ministry of Health. The “Health of the School Child” by the Chief Medical Officer of the Department of Education contains much valuable information.

TABLE C

ORGANISATIONS CONCERNED WITH THE DEAF PERSON (together with date of formation of original body)

(a) 1880 British Deaf and Dumb Association (now British Deaf Association)

(b) Early Council of Church Missioners to the Deaf and Dumb. 1900s

(c) 1911 National Institute for the Deaf (now Action on Hearing Loss)

(d) 1917 National College of Teachers of the Deaf.

(e) 1922 Central Advisory Council for the Spiritual Care of the Deaf and Dumb.

(f) 1928 Deaf Welfare Examination Board.

(g) 1943 British Association of Otolaryngologists.

(h) 1944 National Deaf Children’s Society.

(i) 1947 British Association for the Hard of Hearing.

(j) 1949 Association of Non Maintained Schools for the Deaf.

(k) 1950 Society of Audiology Technicians.

(l) 1952 National Council of Missioners and Welfare Officers to the Deaf.

(m) 1954 Association for Experiment in Deaf Education.

(n) 1958 Society of Hearing Aid Audiologists.

(o) 1959 Society of Teachers of the Deaf.

(p) 1959 Commonwealth Society for the Deaf.

TABLE D

CATEGORIES OF CHILDREN WITH DEFECTIVE HEARING CONSIDERED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AS REQUIRING SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL TREATMENT.

“DEAF PUPILS” are defined as “pupils who have no hearing or whose hearing is so defective that they require education by methods used for deaf pupils without naturally acquired speech or language.” (Definition unchanged since 1945).

“PARTIALLY DEAF PUPILS” were defined in 1945 as “pupils whose hearing is so defective that they require for their education special arrangements or facilities but not all the educational methods used for deaf pupils”. In 1953, this definition was changed to “pupils who have some naturally acquired speech and language, but whose hearing is so defective that they require for their education special arrangements or facilities although not necessarily all the educational methods used for deaf pupils”. In 1962, the term “partially deaf pupils” was changed to “partially hearing pupils” without any change in the definition itself.

Charles Birtwistle was born in Rochdale in 1850. Being deaf from birth, he was sent to the Old Trafford school in Manchester, where he learnt with the ‘silent’ or manual method. His father was a warehouseman, according to the 1862 Manchester Annual Report, who paid £2 12s a year in fees. He joined the school on the 26th of July, 1858, so he would have left (p.12). The census shows that his older brother James (born 1847) was also ‘deaf and dumb’ and he had joined the school on the 31st of July, 1854, at which time their father was paying £5 4 s per year in fees. The headmaster at that time was Patterson, and F.G.C. Goodwin was one of the teachers.

Charles Birtwistle was born in Rochdale in 1850. Being deaf from birth, he was sent to the Old Trafford school in Manchester, where he learnt with the ‘silent’ or manual method. His father was a warehouseman, according to the 1862 Manchester Annual Report, who paid £2 12s a year in fees. He joined the school on the 26th of July, 1858, so he would have left (p.12). The census shows that his older brother James (born 1847) was also ‘deaf and dumb’ and he had joined the school on the 31st of July, 1854, at which time their father was paying £5 4 s per year in fees. The headmaster at that time was Patterson, and F.G.C. Goodwin was one of the teachers. Close

Close