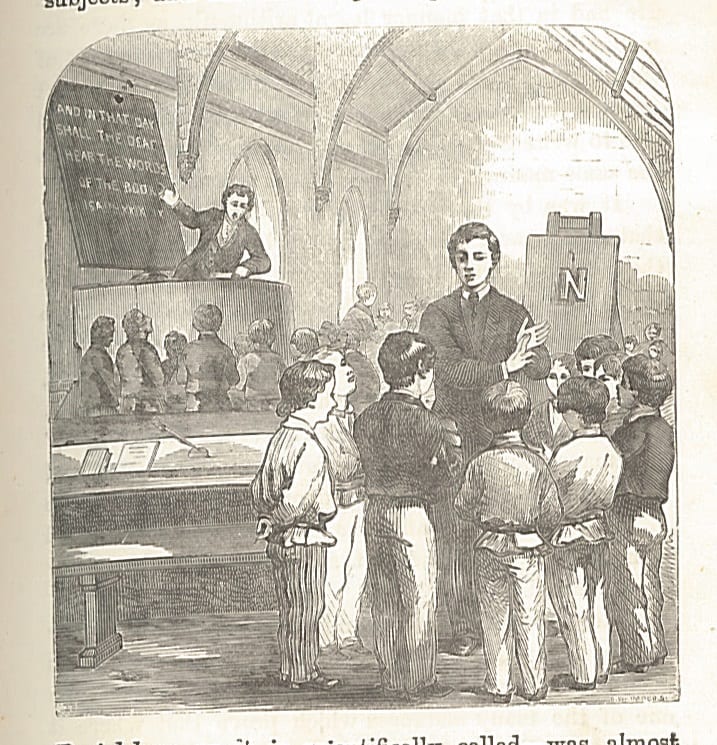

Leslie Edwards was born in Wanstead, Essex, on the 27th of December, 1885, fourth of a remarkable thirteen children. His father, Samuel, from Hackney, was a stock jobber and later a stockbroker’s clerk, while his mother Harriet, was born in Bethnal Green. Leslie lost his hearing through meningitis when he was seven years old, according to both the 1911 and 1901 censuses, though the Teacher of the Deaf (ToD) says nine. He was fortunate that his family learnt to finger-spell which helped his education he said (ToD, p.194). “It was this personal experience which led him throughout his life to advocate the use of finger-spelling, not to supplant oralism, but to provide those accurate patterns of words and sentences so essential to the acquirement of fluency in the use of language” (ibid, p.194-5). He was educated at the Manchester Institution, according to W.R. Roe in Peeps into the deaf world, and London according to the Teacher of the Deaf obituary (by W.C. Roe I believe). Perhaps both are true, though London does seem more likely.

In 1900 he went to art school to train as an advertising artist (ToD p.195). On leaving art school in 1903, he worked as a lithographer, according to the 1911 census, yet another of the large number of Deaf people who learnt that trade. He became a lay reader at the Royal Association for the Deaf and Dumb mission in West Ham.

In 1912 Edwards became an assistant teacher at the East Anglian School for the Deaf in Gorleston, Suffolk. While there he met Marion Thorp, a Yorkshire born teacher of the deaf who had previously trained under William Nelson in Stretford, at the Manchester Institution (Deaf School). Her father Robert was a Church of England clergyman. They were married in 1916, and had two children, a son and daughter (ToD p.195).

We have a 17 page typescript speech on welfare work that he gave in June 1950 to the Torquay Conference for Teachers of the Deaf, when his obituary says he ‘possessed the art of “putting it across,”‘ in his ‘harsh’ but ‘perfectly intelligible’ speech (ToD p.195). For those interested in the development of oralism v. manualism it is worth reading at greater length.

We have a 17 page typescript speech on welfare work that he gave in June 1950 to the Torquay Conference for Teachers of the Deaf, when his obituary says he ‘possessed the art of “putting it across,”‘ in his ‘harsh’ but ‘perfectly intelligible’ speech (ToD p.195). For those interested in the development of oralism v. manualism it is worth reading at greater length.

The Sign Language is essential. The word language is not necessarily confined to words, my dictionary gives several definitions one of which is “any manner of expression.” In so far then as signing conveys ideas, gives information and increases knowledge, it is not incorrect to speak of Sign Language.

No responsible person wants to sign if it can be avoided.

[….]

If signing is to be disregarded and as far as possible suppressed as has been the case for so many years what satisfactory alternative is proposed. Is it not time to face up to the fact that efforts to suppress this natural instinct have not been successful and are bound to fail. (Edwards 1950, p.5)

He develops this line of thinking, further on saying,

Many of you learnt French at school and I think it is reasonable to suggest you acquired about as much understanding of that foreign language as the born deaf do of their Mother Tongue. How many of you enjoy sitting down to read a French novel? (Edwards, 1950, p.6)

From 1915 until his death, he was the missioner at Leicester Mission. Related to that was his work as a founder of the Joint Examination Board for Missioners to the Deaf in 1929, which gave a diploma to missioners and welfare workers.

From 1915 until his death, he was the missioner at Leicester Mission. Related to that was his work as a founder of the Joint Examination Board for Missioners to the Deaf in 1929, which gave a diploma to missioners and welfare workers.

He was the honorary secretary-treasurer for the British Deaf and Dumb Association from 1935 to his death, and received the O.B.E. for his work with the deaf, in 1949 (ToD p.195).

Academic qualifications, to quote his own words, he had none. He needed none. He did possess that indefinable quality which for want of a better word we term genius. Nature ordained that he should be an artist and in deference to her command he sought, for a time, to utilize the gifts she had bestowed on him. But in early manhood he found his true vocation and from then throughout his life the over-ruling factor was his unwavering determination to serve his fellow deaf. (McDougal)

He died on the 3rd of October, 1951.

Ayliffe, E., Obituary. Deaf News, 1951, 188, insert.

Census 1891 – Class: RG12; Piece: 1352; Folio: 68; Page: 38; GSU roll: 6096462

Census 1901 – Class: RG13; Piece: 1621; Folio: 90; Page: 13

Census 1911 Edwards – Class: RG14; Piece: 9703; Schedule Number: 69

Census 1911 Thorp – Class: RG14; Piece: 23656; Page: 1

EDWARDS, L, Adult Deaf Welfare Work. 1950, p.2.

McDOUGAL, K.P. Leslie Edwards: an appreciation. Silent World, 1951, 6, 174.

Memorial to the late Leslie Edwards: Loughborough Church for the Deaf beautified. British Deaf News, 1955, 1, 10-12.

Opening programme, 18 July 1961. Leicester and County Mission for the Deaf, 1961. pp. 11-12.

ROE, W,R, Peeps into the deaf world, Bemrose, 1917, p. 388.

SMITH, A. Leslie Edwards, OBE: his early days. Books and Topics, 1951, 17, 6-7.

The late Leslie Edwards, OBE. Teacher of the Deaf, 1951, 49, 194-95.

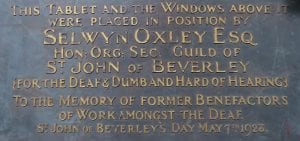

In our collection of artifacts, we have, bizarrely, three stained glass windows. The windows were placed at 5 Grange Road, Ephphatha House, where Selwyn and Kate Oxley moved to when they got married in 1929. Oxley’s mother bought the house on his behalf, originally as a home for the library of the Guild of St. John of Beverley. The Guild deserves an entry of its own on the blog, for it was a repeating theme in Oxley’s life, & before his time it had its beginnings in the North of England with Ernest Abrahams and George Stephenson, among others. When Oxley discovered it he seems to have taken it over, and as he wife mentions several times in her biography of him, Man with a Mission, he loved ceremonies and the associated ‘dressing up.’ Essentially it was a religious organisation, that particularly in the early years of the century, involved a sort of pilgrimage to Beverley, or at least annual services commemorating him and his ‘miracle’ healing a deaf man.

In our collection of artifacts, we have, bizarrely, three stained glass windows. The windows were placed at 5 Grange Road, Ephphatha House, where Selwyn and Kate Oxley moved to when they got married in 1929. Oxley’s mother bought the house on his behalf, originally as a home for the library of the Guild of St. John of Beverley. The Guild deserves an entry of its own on the blog, for it was a repeating theme in Oxley’s life, & before his time it had its beginnings in the North of England with Ernest Abrahams and George Stephenson, among others. When Oxley discovered it he seems to have taken it over, and as he wife mentions several times in her biography of him, Man with a Mission, he loved ceremonies and the associated ‘dressing up.’ Essentially it was a religious organisation, that particularly in the early years of the century, involved a sort of pilgrimage to Beverley, or at least annual services commemorating him and his ‘miracle’ healing a deaf man. I am not sure who the artist was, but Katherine Oxley says they were done by

I am not sure who the artist was, but Katherine Oxley says they were done by They were unveiled in situ on the staircase by the Guild Warden, the Rev. W. Raper, ‘in his robes of office, carried the business through with a grave dignity’ (K. Oxley, 1953). I have chosen the two smaller ones to photograph, as the St. John one is rather larger & harder to get out.

They were unveiled in situ on the staircase by the Guild Warden, the Rev. W. Raper, ‘in his robes of office, carried the business through with a grave dignity’ (K. Oxley, 1953). I have chosen the two smaller ones to photograph, as the St. John one is rather larger & harder to get out.

Close

Close