“There are two classes of deaf people” – Charles John Macalister

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 10 October 2014

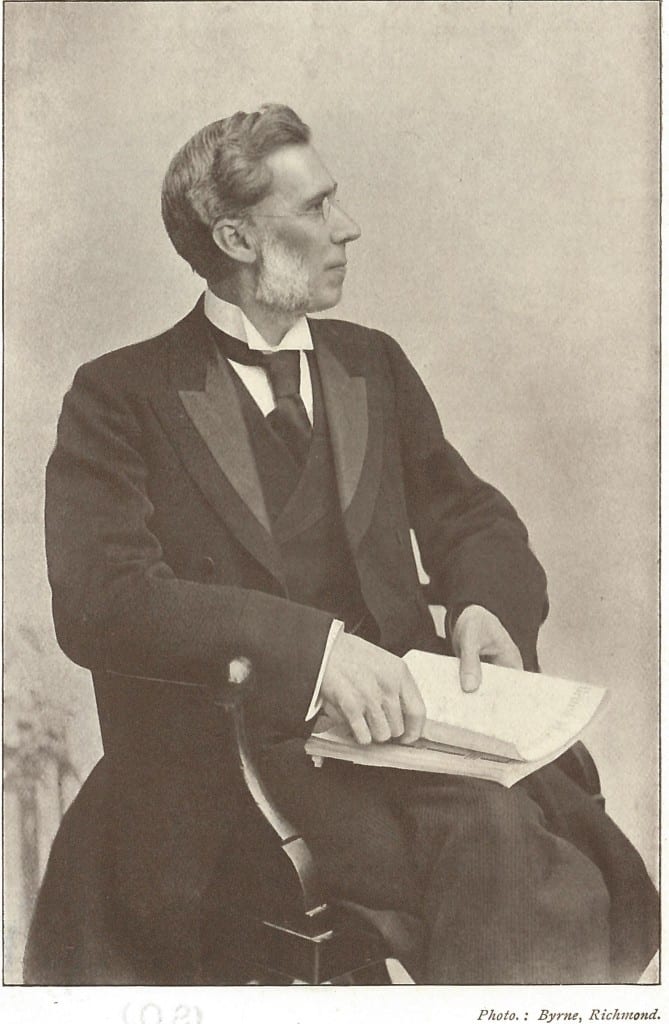

Charles John Macalister (1860-1943) was the third son of William Boyd Macalister of Bootle, who was a ship owner. Charles went into medicine, but chose to study in Edinburgh, before returning to Liverpool.

We are told that he “formed a lifelong attachment to the Royal Southern Hospital, and from 1892 to 1900 was also physician to the Stanley Hospital. He interested himself particularly in children’s diseases and promoted the foundation of the Royal Liverpool Children’s Hospital.” (Lives of the fellows)

He was one of the earliest to recognise the value of ultraviolet therapy. He also worked for long at the stimulation of healing of wounds and (with Benjamin Moore) at the possibility of anti-neoplastic factors in the embryo and young infant. He may not have had spectacular success in either of these difficult fields, but undoubtedly his questing mind was a stimulus to his fellow workers. (Lancet Obituary)

He became involved in the Liverpool Institution and the Liverpool Benevolent Society, perhaps originally in his role of (honorary) consulting physician to the school. He must have been on familiar terms with the great Deaf Liverpudlian, George Healey (1843-1927) Missioner to the Deaf, at the Liverpool Adult Deaf and Dumb Benevolent Society.

What is interesting for us is that from his close association with deaf children in Liverpool, he formulated clear ideas about how they should be best educated.

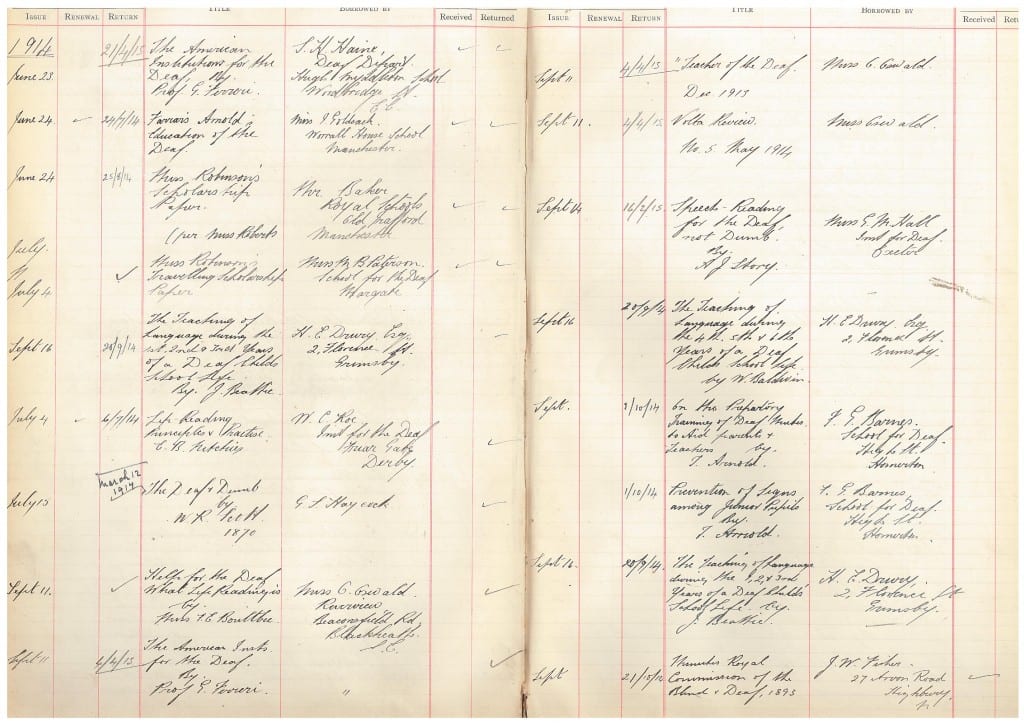

I have scanned and attached the short article, Deaf Mutes and Their Education, that Macalister published in the Liverpool Medico-Chirurgical Journal in January 1891. In this article Macalister begins,

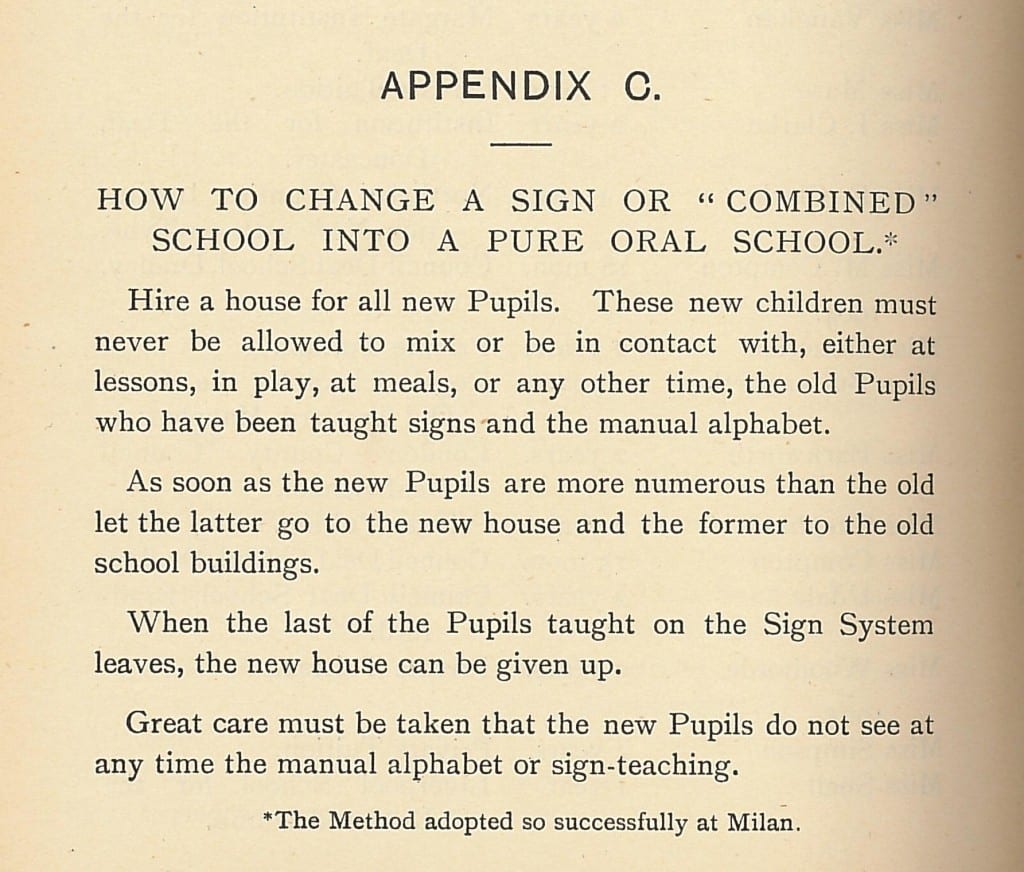

In October 1889 I brought before the Medical Institution some points bearing upon the education of deaf mutes, my object then being to show that, for the masses of the deaf, the pure oral system (as recommended by the Royal Commission on the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind, the report of which had just been issued) is not so satisfactory as is the combined method. [p.60]

[…the author reviews the history of deafness and then discusses three main methods of deaf education, signs, oralism and combined…]

In considering the question as to which of these three systems is most suitable as a general means of education for the deaf, we have to take into account that there are two classes of deaf people to deal with, viz., those who are totally deaf and have been so since birth, and those who were once able to hear and speak, or who remain still susceptible to loud sounds. And, again, we must distinguish very importantly between the rich and the poor, for the means taken to educate the one must be recognised as being sometimes unsuited to the other. It is not my wish to define which method should be adopted in the case of those that are well-to-do – they can get the advantage of private tuition, and the amount of time spent over their education is not of importance; and I have no doubt that for them, as well as for those who can hear a little, or who were once able to speak, the pure oral system is worthy of adoption, and has met with much success. [p.70-1]

His view contrasts with that of Patterson in Manchester, who became a late convert to the Oral method of education (see previous blog entry).

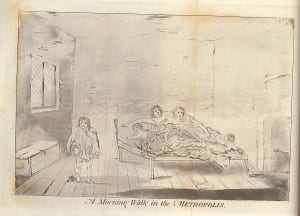

Below is the Liverpool School as it appeared a generation before, in 1853.

Obituary, Lancet, 1943 Volume: 242 Issue: 6271 Page: 589- 90

Charles John Macalister [Who Was Who, accessed 10/10/2014]

Lives of the Fellows [accessed 10/10/2014]

Close

Close

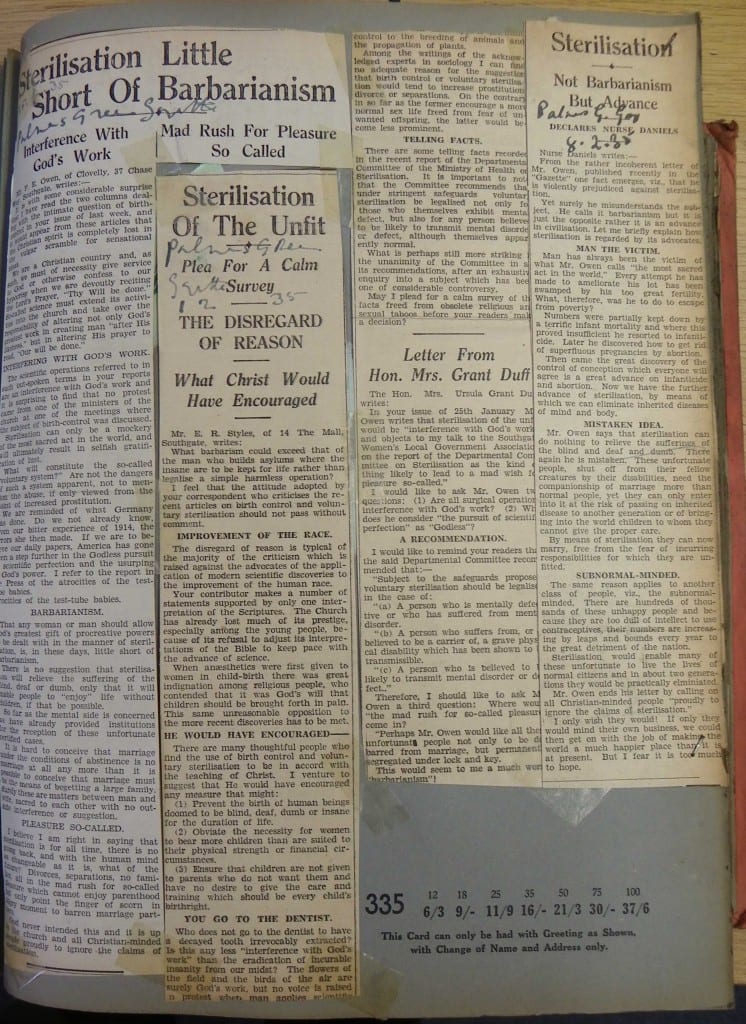

The Home is financed by payments made for the girls and their babies by those responsible for sending them to the Home, usually Public Assistance Committees, and by the grant from the L.C.C., these represent, roughly, two thirds of the total cost, leaving the final third, about £350 to be met by subscriptions and donations. The Committee decided last year to raise the charge made for the maintenance of the girls but it is impossible to raise it sufficiently to cover the whole cost and the Committee therefore appeal again for increased supposrt in the for of subscriptions and donations, an additional £250 p.a. is needed.

The Home is financed by payments made for the girls and their babies by those responsible for sending them to the Home, usually Public Assistance Committees, and by the grant from the L.C.C., these represent, roughly, two thirds of the total cost, leaving the final third, about £350 to be met by subscriptions and donations. The Committee decided last year to raise the charge made for the maintenance of the girls but it is impossible to raise it sufficiently to cover the whole cost and the Committee therefore appeal again for increased supposrt in the for of subscriptions and donations, an additional £250 p.a. is needed.