Author: Shiba Rabiee, recent postgraduate student from IRDR, UCL. Shiba.rabiee.20@ucl.ac.uk | Linked In

Mars is approximately half of the size of Earth and is the fourth planet from the Sun. Due to its many similarities with Earth, Mars is argued to be the second most habitable planet in our solar system. The definitive goal has, therefore, always been a human exploration mission on Mars. After decades of research and space agencies working towards this goal, the founder of SpaceX, Elon Musk, announced in an interview that by 2026 they would be able to send astronauts to Mars in cooperation with NASA [1].

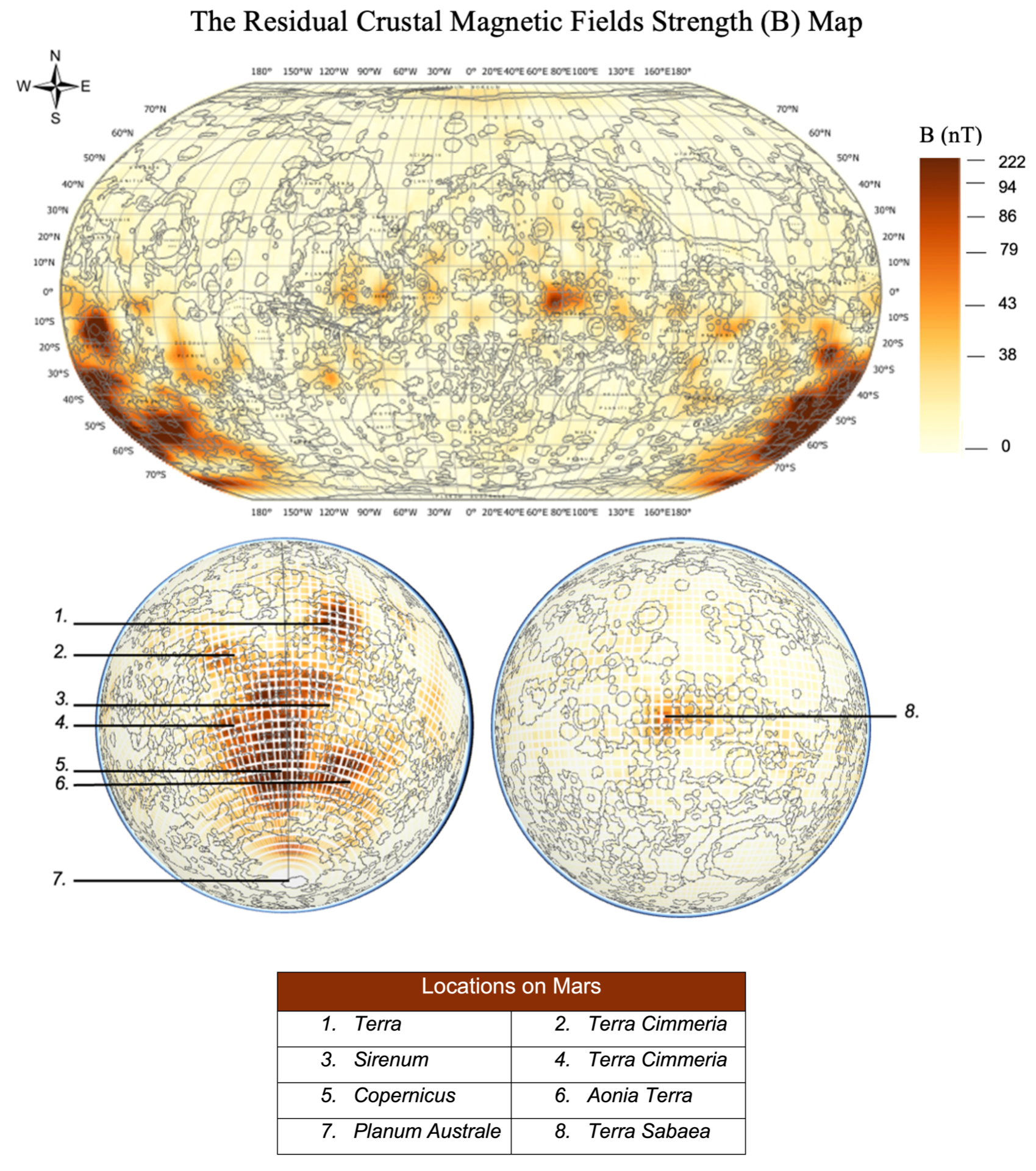

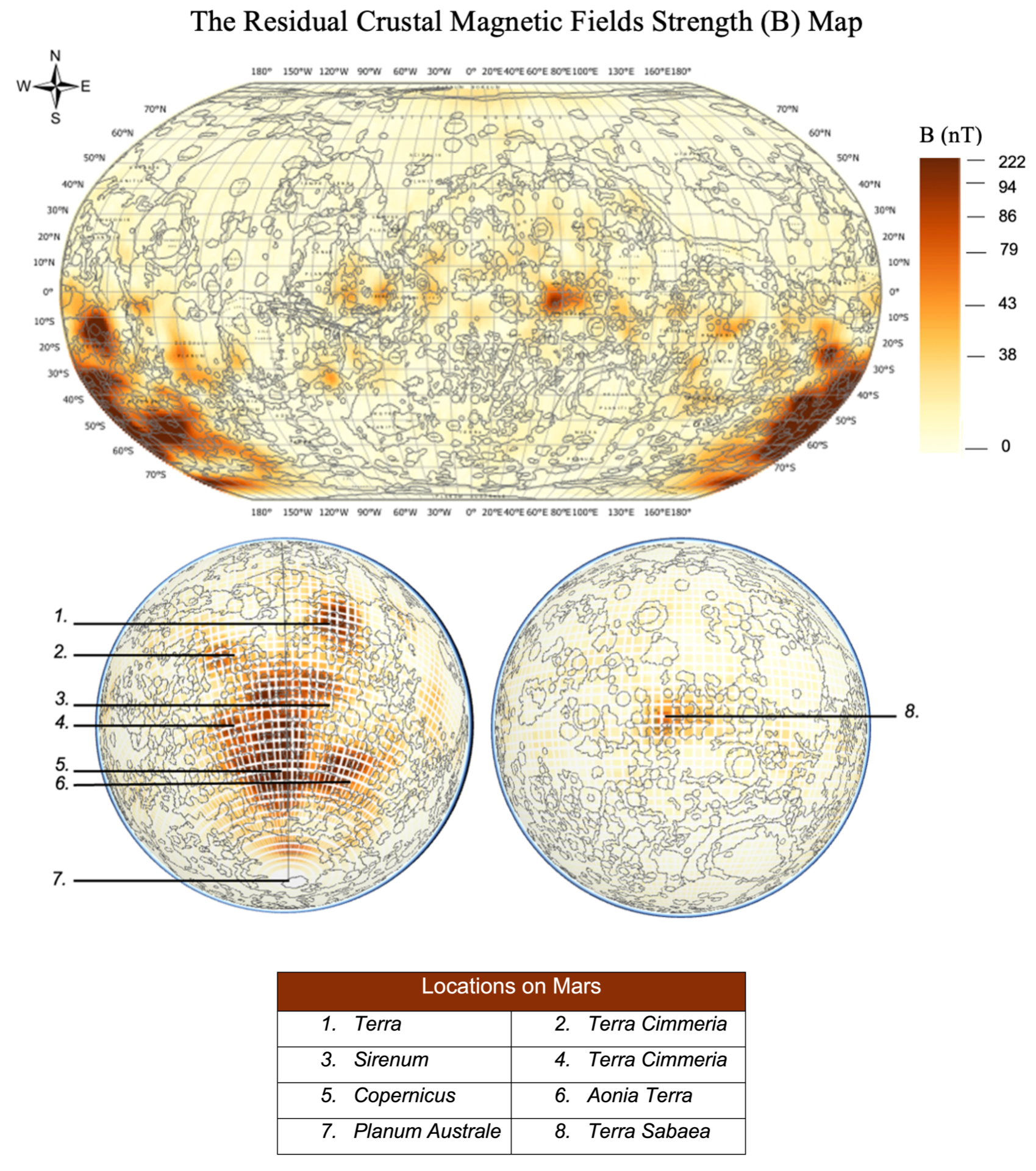

However, in deep space astronauts are exposed to dangerous levels of space radiation (i.e. Galactic Cosmic Radiation and Solar Energetic Particles), and Mars is no exception despite its similarities with Earth. In contrast to Earth’s dense atmosphere enabled by its global dipole magnetic field, Mars has residual crustal magnetic fields that cause a very thin atmosphere (~1% of Earth’s) [see Illustration 1] [2, 3]. This creates a highly radioactive and complex environment on Mars that has detrimental, and ultimately lethal, effects for astronaut’s health [3-5].

(Illustration 1. Source: Shiba Rabiee [panel a., created in Microsoft Word]; Kevin M. Gill [panel b., with modifications by Shiba Rabiee]. Cartoon illustrating the global dipole magnetic field of Earth (panel a.) and the residual crustal magnetic fields of Mars (panel b.)).

Throughout the years of sending astronauts into Low Earth Orbit (160-1000 km altitude above Earth), medical doctors and psychiatrists working with astronauts have noticed a decrease in their holistic health when operating a space mission [6, 7]. Space agencies have, therefore, several times encouraged engineers to develop mitigation measures for high radiation exposure but without much success. Shielding measures are essential, yet many issues arise with the creation of shielding such as high financial expense, how to transport the shielding to Mars, and how the material(s) will act in the Martian environment. Space radiation is, therefore, generally acknowledged as a potential barrier for human exploration missions both during Cruise-Phase and whilst on a planet or moon [8].

As space agencies try to create innovative solutions for spacecrafts and crewmembers during Cruise-Phase for a Mars mission, bigger challenges await when arriving on the red planet. A mission to Mars would require astronauts to stay on the planet for several weeks due to the distance between Mars and Earth. In combination with the Martian environment, long-duration space exploration poses several risks and increases the vulnerability to multiple hazards amongst both crewmembers and spacecrafts. Thus, in order to ethically send astronauts to Mars, the radiation problem has to be solved. Research to investigate the mitigation of radiation exposure and associated risks is important to protect good health.

The complexity of creating and transporting affordable mitigation measures has left space agencies with the question of whether to use resources from the Martian environment. A promising mitigation measure currently being discussed is the use of the Martian regolith as a shielding measure by creating a habitat of tunnels beneath the surface of Mars. Yet, this will not provide shielding for astronauts undergoing an extravehicular mission (spacewalk). A human exploration mission will, however, demand exploration of the Martian environment outside the habitat. The need for further investigation and the development of additional mitigation measures, therefore, remains.

The objective of my thesis was to investigate the use of the residual crustal magnetic fields of Mars as a mitigation measure against space radiation exposure during e.g., extravehicular missions. Research on the magnetic fields have been previously conducted [8-16], wherefrom the general argument is that the Martian atmosphere and the magnetic fields provide an equal amount of shielding against space radiation [8] [16]. Yet, these were founded on hypotheses as the Martian atmosphere was not considered during the simulation models [8]. Thus, it was unknown whether the atmosphere could, in fact, provide corresponding shielding measures.

The Martian atmosphere has roughly two orders of magnitude smaller column density than that of Earths and comprises ~95.1% carbon dioxide [16-19]. This, in combination with continuing atmospheric escape, causes the Martian atmosphere to provide almost no shielding against space radiation. Depending on the solar cycle and the chosen location, the estimations conducted for the thesis does, however, imply a potential prolonged extravehicular mission of e.g., ~34 sec/day to ~74 min/day within a field strength of 14 nT [see magnetic fields strength map for the range of field strengths measured at 400 km altitude]. These estimates will increase with increasing field strengths, thus, indicating that the residual crustal magnetic fields can be used as a mitigation measure. Moreover, the estimates imply a significant difference between shielding provided by the atmosphere and the residual crustal magnetic fields.

(Illustration 2. Source: Shiba Rabiee. Data source: Planetary Geologic Mapping Program; The Planetary Data System; the ArcGIS ESRI geodatabase. Map presenting the residual crustal magnetic field strengths measured by Mars Global Surveyor at 400 km altitude).

This conclusion is founded on methods and various assumptions. To confirm the results presented, further investigation of the residual crustal magnetic fields needs to be completed. Suggestions for potential future missions and research has, therefore, additionally been presented and discussed in the thesis.

Mars has been argued to have looked very similar to Earth ~3.8 billion years ago [see Illustration 3] [20]. Further investigations of the residual crustal magnetic fields of Mars will not only enable an understanding of its potential to act as a shielding measure, but similarly to Mars, atmospheric escape can also be found on Earth. Yet, despite long investigations of Earth’s atmospheric escape many questions remain unanswered. A comprehensive investigation of the residual crustal magnetic fields and its relation to the Martian environment could, therefore, inform about the core of Mars and the planets atmospheric escape, consequently enabling an understanding of the atmospheric leakage on Earth. Research in this area may provide essential information of what could be the future of Earth.

(Illustration 3. Source: Kevin M. Gill [modifications by Shiba Rabiee]. Depiction of the evolution of Mars from ~3.8 billion years ago (left) to the Martian environment today (right)).

Shiba Rabiee is a recent postgraduate student from IRDR, UCL. Email at Shiba.rabiee.20@ucl.ac.uk| Linked In

References

[1] Wall, Mike (2020): SpaceX’s 1st crewed Mars mission could launch as early as 2024, Elon Musk says. SPACE.com. https://www.space.com/spacex-launch-astronauts-mars-2024 [Accessed 17.02.2021].

[2] Matthiä, Daniel; Hassler, Donald M.; Wouter de Wet; Ehresmann, Bent; Firan, Ana; Flores-McLaughlin, John; Guo, Jingnan; Heilbronn, Lawrence H.; Lee, Kerry; Ratliff, Hunter; Rios, Ryan R.; Slaba, Tony C.; Smith, Micheal; Stoffle, Nicholas N.; Townsend, Lawrence W.; Berger, Thomas; Reitz, Günther; Wimmer-Schweingruber, Robert F.; Zeitlin, Cary (2017): The radiation environment on the surface of Mars – Summary of model calculations and comparison to RAD data. Life Science in Space Research, Volume 14. pp. 18-19.

[3] Hassler, Donald M.; Zeitlin, Cary; Wimmer-Schweingruber, Robert F.; Ehresmann, Bent; Rafkin, Scot; Eigenbrode, Jennifer L.; Brinza, David E.; Weigle, Gerald; Böttcher, Stephan; Böhm, Eckart; Burmeister, Soenke; Guo, Jingnan; Köhler, Jan; Martin, Cesar; Reitz, Guenther; Cucinotta, Francis A.; Kim, Myung-Hee; Grinspoon, David; Bullock, Mark A.; Posner, Arik; Gómez-Elvira, Javier; Vasavada, Ashwin; Grotzinger , John P.; MSL Science Team (2014): Mars’ Surface Radiation Environment Measured with the Mars Science Laboratory’s Curiosity Rover. Science. Volume 343, Issue 6169, 1244797. pp. 1-6.

[4] National Aeronautics and Space Administration [NASA] (2020): What is space radiation?. NASA. https://srag.jsc.nasa.gov/spaceradiation/what/what.cfm [Accessed 08.08.2021].

[5] National Aeronautics and Space Administration [NASA] (2019): NASA’s MMS Finds Its 1st Interplanetary Shock. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2019/nasa-s-mms-finds-first-interplanetary-shock [Accessed 08.08.2021].

[7] Kennedy, Ann R. (2014): Biological effects of space radiation and development of effective countermeasures. Life Sciences in Space Research. Volume 1. DOI: 10.1016/j.lssr.2014.02.004. pp. 10-43.

[8] Durante, Marco (2014): Space radiation protection: Destination Mars. Life Sciences in Space Research. Volume 1. DOI: 10.1016/j.lssr.2014.01.002. pp. 2-9.

[9] Acuña, M.H.; Connerney, J.E.P.; Wasilewski, P.; Lin, R.P.; Anderson, K.A.; Carlson, C.W.; McFadden, J.; Curtis, D.W.; Mitchell, D.; Reme, H.; Mazelle, C.; Sauvaud, J.A.; d’Uston, C.; Cros, A.; Medale, J.L.; Bauer, S.J.; Cloutier, P.; Mayhew, M.; Winterhalter, D.; Ness, N.F. (1998): Magnetic Field and Plasma Observations at Mars: Initial Results of the Mars Global Surveyor Mission. Science. Volume 279, Issue 5357. DOI: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1676. pp. 1676-1680.

[10] Acuña, M. H.; Connerney, J.E.P.; Ness, N.F.; Réme, H.; Mazelle, C.; Vignes, D.; Lin, R.P.; Mitchell, D.L.; Cloutier, P.A. (1999): Global distribution of crustal magnetization discovered by the Mars Global Surveyor MAG/ER experiment.Science. Volume 284, Issue 5415. DOI: 10.1126/science.284.5415.790. pp. 790–793.

[11] Hiesinger, Harald; Head III, James W. (2002): Topography and morphology of the Argyre Basin, Mars: implications for its geologic and hydrologic history. Planetary and Space Science. Vol. 50, issues 10-11. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0032063302000545. pp. 939-981.

[12] Mitchell, D.L.; Lillis, R.J.; Lin, R.P.; Connerney, J.E.P.; Acuña, M.H. (2007): A global map of Mars’ crustal magnetic field based on electron reflectometry. Journal of Geophysical Research 2007. Vol. 112, EO1002. Doi: 10.1029/2005JE002564. pp. 1-9.

[13] Dartnell, L.R.; Desorgher, L.; Ward, J.M.; Coates, A.J. (2007): Martian sub-surface ionizing radiation: biosignatures and geology. Biogeosciences. Volume 4, Issue 4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-4-545-2007. pp. 545-558.

[14] Lesur, V., Hamoudi, M., Choi, Y., Dyment, J., & Thébault, E. (2016). Building the second version of the World Digital Magnetic Anomaly Map (WDMAM). Earth Planets Space, 68, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-016-0404-6. pp. 1-13.

[15] Langlais, Benoit; Thébault, Erwan; Houliez, Aymeic; Purucker, Micheal E.; Lillis, Robert J. (2019): A New Model of the Crustal Magnetic Field of Mars Using MGS and MAVEN. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. Volume 124. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1029/2018JE005854. pp. 1542-1569.

[16] Carr, M.H. (1996): Water on Mars. Oxford University Press. Environmental Science, Physics Bulletin. Volume 38. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9112%2F38%2F10%2F017. pp. 374-375.

[17] Jakosky, B.M.; Slipski, M.; Benna, M.; Mahaffy, P.; Elrod, M.; Yelle, R.; Stone, S.; Alsaeed, N. (2017): Mars’ atmospheric history derived from upper-atmosphere measurements of 38Ar/36Ar. Science. Volume 355, Issue 6332. DOI: 10.1126/science.aai7721. pp. 1408-1410.

[18] Nier, A.O.; Hanson, W.B.; Seiff, A.; McElroy, M.B.; Spencer, N.W.; Duckett, R.J.; Knight, T.C.D.; Cook, W.S. (1976): Composition and Structure of the Martian Atmosphere: Preliminary Results from Viking 1. Science. Volume 193, Issue 4255. DOI: 10.1126/science.193.4255.786. pp. 786-788.

[19] Nier, A.O.; McElroy, M.B. (1977): Composition and Structure of Mars’ Upper Atmosphere: Results From the Neutral Mass Spectrometers on Viking 1 and 2. AGU. Journal of Geophysical Research. Volume 82, Issue 28. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/JS082i028p04341. pp. 4341-4349.

[20] National Aeronautics and Space Administration [NASA] (2017): The Look of a Young Mars. NASA.https://www.nasa.gov/content/goddard/the-look-of-a-young-mars-3 [Accessed 25.08.2021].

Illustrations and Map

Gill, Kevin M. [modified by Shiba Rabiee] (2015): Mars. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/53460575@N03/16716283421 [Accessed 13.10.2021].

ArcGIS: ESRI geodatabase – ESTRI_ASTRO. https://www.arcgis.com/home/user.html?user=esri_astro [Accessed: 10.05.2021].

NASA: Planetary Data System. https://pds-ppi.igpp.ucla.edu/search/?t=Mars&facet=TARGET_NAME [Accessed: 27.05.2021].

USGS; NASA: The Planetary Geologic Mapping Program. https://planetarymapping.wr.usgs.gov [Accessed: 04.05.2021].

Gill, Kevin M. [modified by Shiba Rabiee] (2015): Evolution of Mars. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/53460575@N03/17234143751 [Accessed 14.10.2021].

Filed under IRDR Space Health Risks Research Group (SHRRG), Miscellaneous, Student Research

Tags: astronauts, DRR, IRDR, magnetic fields, mars, mission, mitigation, radiation, residual crustal, space

No Comments »

Close

Close