Author: Savin Bansal

The cataclysmic ‘Kedarnath tragedy’ of June 2013, triggered by overwhelming flash-floods and landslides in Uttarakhand, the Greater Himalayan State of India, instigated losses worth US$ 1billion, mortality at a gory high of 5000 and led to an equal number still being reported as missing. The destruction of critical infrastructure left several lakhs of pilgrims and tourists stranded for several weeks together.

The region has been long fraught with frequent, severe and uncertain onslaught of geophysical and hydrometeorological hazards, is seismically dynamic, afflicted with climatic extremes and is witness to the growing human-environment interactions. Though the moderate magnitude events probably have become a reality in the region, the 2013 hydrometeorological extreme remains unique in terms of the historic trends and exceedance probability.

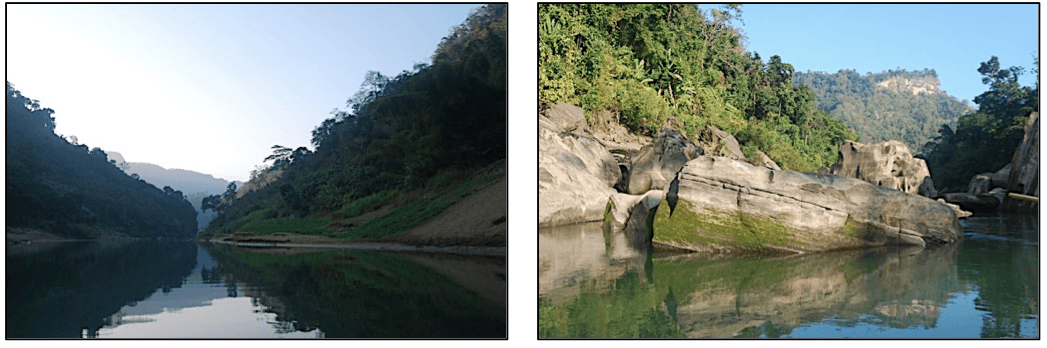

The monsoon in June 2013 arrived almost two weeks earlier than expected. The torrential cloudbursts and massive Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF) resulted in a sudden swelling of the Mandakini, Alakananda, Bhagirathi and Kali river basins. Being a renowned pilgrimage and eco-tourism circuit in India, the region saw the disaster coinciding with the peak congregation, affecting more than 900,000 lives and precipitating grave infrastructure failure in just over three days. The towns of Kedarnath, Rambara and Gaurikund dotted along the Mandakini valley bore the maximum brunt.

The aftermath rendered the key public assets and critical infrastructure dysfunctional, and the exigent business processes compromised. The ravaged quintessential schools-hospitals, buckled highways and bridges, wrecked civic service delivery systems, snapped telecommunication networks, and incapacitated fire and emergency operation services only amplified the atrocious impacts. This not only compromised the relief-rescue operations but severely subdued the coping capacity of the community.

Chinks in the Armour

Many victims had misled themselves to cascading floods and landslips, several children and elderly to trauma and injuries, with others succumbing to lost will and hope. The disquieting spectacle of vanished settlements, frenzied victims and bewildered response put up a horrendous spectacle to behold. In retrospect, the delayed response and resource sub-optimization are attributed to the iniquitously deficient Risk Management framework detailed as:

Imperception of the significance the resilience holds for critical infrastructural systems:

The colossal impact was strikingly disproportionate to the infrastructure resilience levels, adaptation and coping capacities of the communities. Ironically, it took a catastrophe of such a stupendous magnitude to realise the growing reliance of society upon interconnected functional nodes and closely coupled systems. The setbacks on such systems empowered vulnerabilities to generate escalation points that spawned devastating cascades further to propagate through socio-economic systems.

Information asymmetry and risk communication deficit:

The small-scale pre-disaster (preparedness phase) knowledge sharing and generalized oblivion about risk perception and assessment among the emergency response agencies, media, volunteers, and local inhabitants denied the potential victims an opportunity to take informed decisions to protect themselves.

Inconsiderate of known-knowns:

Lack of preparedness, scenario planning, functional disaster management and resilience plans, decentralized resource inventories and inept Emergency Operation Centres accentuated the vulnerability and limited the Hazard risk-vulnerability-analysis (HRVA) capability. The underdeveloped forecasting and early warning systems subdued the evacuation mechanisms and alert protocols further.

Benighted and at odds with the idea of inter-agency coordination and collaboration:

The existence of multiple information flowlines and command structures only rendered the response entities confounded and aid agencies disoriented. It proliferated the unverifiable inputs and compromised priority sequencing. The squandering of initial golden hours of search-rescue owed itself substantially to this fallacy.

Joint Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment

The multi-sectoral damage and needs assessment carried out by the Government in collaboration with the multilateral development institutions (the World Bank and Asian Development Bank) laid the framework for stimulating major policy shift to proactive risk management besides sustainable recovery and reconstruction.

Massive investment mix in the form of IDA (International Development Assistance) and federal assistance were deployed for Risk Reduction Investments in (i) multi-hazard resilient assets such as strategic roads and bridges, public schools, and hospitals, (ii) augmenting emergency response capacities through provisioning of modern search-rescue equipment and training, (iii) bolstering hydro-meteorological network and Early Warning Systems (EWS), (iv) establishment of a risk assessment-modelling framework and a geospatial decision support system, (v) and institutionalising the Uttarakhand State Disaster Management Authority (USDMA) to operate and function in conformance with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-30).

Lessons Learned

Eventually, taking the event in its stride, the State has literally risen from the ashes by drawing on the lessons learned in its wake. The pace of recovery and policy instruments deployed have been exemplary. The Risk Management framework developed is espoused as a best-practice model and now serves as a blueprint for other state entities and the neighbouring Himalayan nations.

Being at the core of economy, critical infrastructure was duly recognised as the central factor in enabling labour productivity, redistributive justice and serving our most basic needs to assuring a decent quality of life. Any disruptions therein are a drag on economies that disconcert communities through denting households’ consumption, well-being, and the productivity.

Hence, the formal mechanisms to appraise the cost-benefit ratio of ex-ante policy measures do exist now insomuch as critical asset resilience is concerned. This assumes substance in the context of minimizing the recurrent disruptive shocks on infrastructure and livelihoods, and averting the prohibitively high ex-post reconstruction cost. A pre-emptive investment in more resilient infrastructure is clearly a cost-effective and robust choice, the net result of which is a $4 in benefit for each dollar invested in resilience.

Furthermore, the policy commitments for increased resource allocation towards disaster-climate risk mitigation, reinforced multi-hazard Early Warning Systems, fully equipped District Emergency Operation centres and risk informed development planning are a reality of the day.

In addition, Incident Response System (IRS), a structured framework that enhances interoperability and behaviour coordination under multi-layered team settings is integrated well into the Emergency Response model of the State. It has proved to be critical in stimulating calibrated response to critical events all this while by bringing the disparate units together to share resources, authority and knowledge.

Conclusion

Overall, every time such low probability tail events fleet past us, they never fail to encourage adopting a paradigm shift in the ways we perceive, respond and live through the hazards. Parting ways with the reactive emergency response regime shall require mainstreaming the Disaster-Risk Reduction into development plans, policy and investments. The bottom line is that the victims endangered by life threatening exigencies don’t deserve such gratuitous procrastination and inefficiencies.

Savin Bansal is an Indian civil servant (Indian Administrative Service) and presently pursuing a Master’s degree in Risk, Disaster and Resilience at IRDR, University College London. Serving the Government of Uttarakhand, India, as an administrator and public policy practitioner, he has an extensive experience in Disaster-Climate risk management domain as a decision-maker and leading multilateral development projects.

Contribute to the discussion: savin.bansal.21@ucl.ac.uk

Disclaimer: The views and perceptions expressed are in personal capacity and can’t in anyway be construed as that of the Government of Uttarakhand, Government of India or the University College London.

Close

Close