From academia to policy: bridging the gap

By Amna Bokhari, on 1 August 2024

During my short time as a research fellow at UCL, seconded from my ‘day job’ as a Clerk in the House of Commons, I have heard the use of the term ‘bubble’ on more than one occasion to describe the sphere in which academics work. The word reminds me of the bubble to which I belong- one that sits in the heart of Westminster. Both worlds, that of academia, and that of policy, are intrinsically connected. Yet, with a foot in both ‘camps’, the gap between the two communities appears to me to be significant. From candid conversations with colleagues here, I have also gathered that it has become increasingly difficult to bridge this gap in recent years.

Without getting into the details of how either ‘bubble’ works, I am struck that engagement with the select committee process may well be the most effective way of bridging this gap and encouraging cross-collaboration. Feeding into government policy is difficult- even from the standpoint of an expert select committee constituted by MPs from across Parliament. I wonder if, through proactive engagement and collaboration, our bubbles may float just that little bit closer together. I also wonder whether select committees, rather than or alongside Government departments, could be the ‘go to’ for academics wanting to share work or insight with those in the world of policy.

Last month, I delivered a presentation on the world of parliamentary select committees to colleagues at UCL’s Department of Risk and Disaster Reduction (RDR), my ‘home’ department at UCL. Colleagues had questions about how we could work together more effectively and bridge the gap between academia and policy. One IRDR colleague proposed that regular roundtables could be set up with committee staff and academics working in a particular area of policy to discuss ideas, priorities and developments. This might also ensure that we are broadening the pool of academics that we are hearing from and give us the key to a diverse range of viewpoints and expertise.

Another colleague asked whether and how submitting written evidence to an inquiry could be effective, particularly if the area of policy is heading in a different direction to academic research findings. I emphasised that the job of a select committee is to scrutinise Government policy, and that well-informed, well-researched evidence is an invaluable contribution to this work, regardless of where the evidence falls. Such evidence may be included and referenced in reports and contribute to the committee’s thinking behind any recommendations they propose. Gathering a range of views is perhaps one of the most effective forms of both outreach and scrutiny from a select committee perspective.

As committee staff, we should at the very minimum ensure academics are aware of who we are, what we do and how to contribute to work we have going on. Likewise, academics should feel empowered to approach select committee staff with any work they feel should be on our radar. This ‘knowledge exchange’ process has indeed been the purpose of my fellowship here at UCL and may well form the foundation for future collaboration and effective scrutiny as we move past the general election and toward the formative months of policy creation that will inevitably follow.

Amna Bokhari is the second clerk on the Joint Committee on Human Rights and has been working in the House of Commons across different committees and policy areas since 2021. She was seconded to UCL across the general election period. This fellowship was supported by UCL Public Policy.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s).

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLRDR

The Global Water Crisis is a Local Problem

By Mohammad Shamsudduha, on 11 July 2024

We often hear that the world is facing an imminent water crisis as demand for freshwater outstrips supply and water quality is degrading globally. This is true for many parts of the world. However, is it accurate to label this a “global water crisis”? The term conjures images of a unified, worldwide struggle against dwindling freshwater resources. This perspective often obscures the true nature of the crisis: a series of highly localised problems that vary significantly from one region to another. Global-level policies, though well-intentioned, frequently fail to address the specific needs and challenges faced by local communities. By examining issues such as groundwater depletion, water quality challenge (e.g., salinity, arsenic, faecal contamination), water poverty, and poor governance, we can better understand why the global water crisis is, in reality, a collection of local problems requiring tailored solutions.

Groundwater depletion in India

According to a World Bank report, India is the largest user of groundwater, extracting over 230 km3 annually, which accounts for about 25% of the global total. Groundwater serves as the lifeline for agriculture, drinking water, and industry across India. Over-abstraction of groundwater, particularly in states like Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh, has led to severe depletion of aquifers. This overuse is driven by policies that encourage water-intensive crops and subsidise electricity for pumping water, without considering the long-term sustainability of water resources. Despite global efforts to promote sustainable water use, the issue persists due to the local agricultural practices (e.g., water-intensive rice crop cultivation) and policy incentives that need to be reformed.

Water salinity in coastal Bangladesh

In coastal Bangladesh, water salinity has become a major concern. New research led by a PhD student at RDR shows that reduction in river discharge, rising sea levels, and frequent cyclones, exacerbated by climate change, have increased the salinity of both groundwater and surface water sources. This has made it difficult for local populations to access fresh drinking water and has adversely affected health and agricultural production. Global climate policies may address the broader issue of climate change, but they do not provide immediate solutions to the salinity problems faced by coastal communities in Bangladesh. Localised strategies, such as building freshwater reservoirs, rainwater harvest, and adopting salt-tolerant crops, are essential to address these specific challenges. A study from the World Bank highlights that over 25 million people in Bangladesh are currently exposed to saline groundwater.

Arsenic contamination in Bangladesh and India

Arsenic contamination of groundwater has been a severe issue in parts of Bangladesh and India, particularly in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Delta since early 1990s. Millions of people are exposed to arsenic levels far above safe limits, leading to serious health problems. Recent reports show that around 20 million people in Bangladesh and 13 million in India are exposed to very high arsenic contamination in drinking water. While international guidelines and global health policies raise awareness about the dangers of arsenic, the solution requires localised intervention. This includes identifying contaminated wells, providing alternative water sources, and educating communities about the risks and mitigation strategies. Global policies cannot replace the need for targeted, on-the-ground action to manage this public health crisis.

Water poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa

Water poverty remains a significant challenge across various regions globally, impacting millions of people daily. In many parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, access to clean water is a daily struggle. Water poverty, defined by lack of access to adequate, safe, and affordable water for a healthy life, affects millions. Global initiatives often focus on large-scale infrastructure projects, but these can overlook the specific needs of remote or impoverished communities. Local solutions, such as community-managed water supply systems, rainwater harvesting, and mobile water treatment units, can be more effective in addressing the unique challenges faced by these populations. According to the United Nations, over 400 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa lack access to basic drinking water services.

Sewage disposal and water pollution in the UK

Here in the UK, ongoing issues with sewage disposal by water companies highlight significant governance failures in managing water resources. Water companies have been criticised for discharging untreated sewage into rivers and coastal waters, leading to severe water pollution. This practice has contaminated waterways, affecting ecosystems and public health. Despite regulatory frameworks intended to protect water quality, enforcement has been lax, and infrastructure investments have lagged. According to the Environmental Agency, in 2023, England’s rivers and seas endured over 3.6 million hours of untreated sewage discharges, a 54% increase from the 1.75 million hours in 2022, with the total number of spills reaching 464,000. This severe water pollution impacts ecosystems and public health, underscoring the urgent need for stronger local governance and enforcement to address these issues effectively. Watershed Investigations has recently published a UK-wide map of water pollution that contains 120 datasets, ranging from river health, bathing water health, to historic landfill sites, sewage dumping, intensive farming, heavy industry and more.

Global awareness and local realities

While the global narrative of a water crisis is useful in creating public and policy awareness, it often fails to solve specific local problems on the ground. Unlike the global climate crisis, which is primarily driven by carbon emissions affecting the entire planet, water issues are highly localised and influenced by regional natural and anthropogenic factors.

Global policies tend to generalise the water crisis, leading to solutions that do not fit local contexts. For instance, the UN’s global water development report highlights broad issues, but without localised strategies, these insights do not translate into actionable solutions on the ground. Global campaigns such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SGD) may raise awareness, produce lots of reports, and mobilise resources but fall short in addressing specific local challenges such as the infrastructural deficits in Sub-Saharan Africa or the unique ecological impacts on Bangladesh’s coastal regions due to water and soil salinity.

Addressing the global water crisis through localised strategies is essential for real change. For instance, India’s severe groundwater depletion due to over-extraction for agriculture necessitates local policy reforms and sustainable water management practices. Coastal Bangladesh faces increasing water salinity from rising sea levels and cyclones, which can be mitigated through localised solutions like freshwater reservoirs, rainwater harvesting and salt-tolerant crops. In Sub-Saharan Africa, sustainable groundwater development, including managed aquifer recharge, solar-powered boreholes, and community-based management, effectively addresses water scarcity. The UK’s severe sewage disposal issues underscore the importance of stringent governance, regulation, and infrastructure investments. These examples illustrate that while global awareness is important, tailored, region-specific interventions (“global water crisis but local solutions”) are critical for effectively addressing diverse water challenges worldwide.

Dr Mohammad Shamsudduha | Department of Risk and Disaster Reduction

Dr. Mohammad Shamsudduha (Shams) is an Associate Professor at UCL RDR, specialising in water crises and risks to human health, irrigated agriculture, and climate adaptation. His research focuses on sustainable water management, water risk, and resilience strategies, with significant contributions to understanding groundwater quality and quantity crises around the world. Dr. Shams has been promoted to Professor of Water Crisis and Risk Reduction, effective from October 2024.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s).

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLRDR

Watching climate politics: can we conduct ethnography of international agreements online?

By Aishath Green, on 14 June 2024

Climate politics is seen in the media through the big annual meetings in cities around the world. The most recent meeting – COP28 – was in Dubai with 80,000 delegates. The flashy gold decorations and green background in the plenary room were captured in selfies and social media posts. But there is another, quieter side to negotiating climate change. Numerous small technical meetings and workshops held in person and online to thrash out specific issues. Often the same core group of negotiators and observers will meet regularly for several years. Much of the detail is worked out in these spaces and they are a crucial research site for understanding climate politics.

Over the past year I have been conducting ethnographic observations of a specific part of the UN negotiations on climate change seeking to define the ‘global playbook’ for adaptation as part of a wider research programme analysing the knowledge politics around adaptation measurement. The area I was following – the Glasgow Sharm el-Sheikh work programme known to those on the inside as the GlaSS – had eight workshops over 2022 and 2023 which I was able to watch online. The process culminated at COP28 in Dubai with the establishment of the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience (UAE-FGCR). I have been able to piece together what influenced this final framework through watching the UNFCCC’s Youtube channel as a contribution to our empirical research. But through doing this, I have also learnt lessons on how to conduct ethnographic research online and what the turn to online might mean for climate politics.

Following a soap opera

In practical terms, conducting digital ethnographic research of the GlaSS workshops meant watching lengthy recordings lasting up to 8 hours long. I followed the twists and turns through multiple breakout groups and plenary discussions. As I watched the recordings of the workshops, I also observed the interactions between online attendees and those who had been present in person. As I transitioned from one workshop to the next, the recordings gave me vital insight into Party and non-Party perspectives on the development of the framework and what mattered most for different contributors. This ranged from firm beliefs such as the importance of financial support to enhance adaptation action, to the smaller details of wording for specific targets. It was like following a soap opera, with each episode revealing slightly more about each character’s position and the same themes of conflict carrying through with each instalment. By the time COP28 came around, I was up to speed just in time to watch negotiations play out on the event’s virtual platform – yet another digital ethnographic lens through which I could keep up to date.

A partial picture

Before I started, there were factors that I knew would impact my analysis. For instance, not being able to observe participants’ body language, pick up as easily on visual cues or feel the sensory aspects of the room. However, as I continued to watch the workshops, I became aware of other aspects that I was missing through my digital lens. As I became familiar with Party representatives and break out group rapporteurs, I began to think more about the voices of those I was not hearing and those in the room the camera did not show. While the recordings (and participating online) enable you to hear the views of the most confident, the perspectives you gain from those who speak in smaller group discussions or perhaps during coffee breaks, are not captured. In a similar vein, by only watching COP28 negotiations online, you are excluded from the important conversations happening in the corridors. An advisor to the Small Island Developing States for instance, remarked that the second week of negotiations relied on trying to understand what was happening in between the formal sessions. With my colleague bringing back some of these vital insights from attending in person, the importance of triangulating digital ethnographic research was clear.

Inclusion of online participants

While I was only getting a partial picture from conducting this research digitally, it did highlight important areas for the future of global agreement making through hybrid spaces. During the GlaSS workshops, there was a clear difference in how the online group and those attending in person were able to participate. During some of the hybrid break out group discussions, while there was an effort by the moderator to incorporate online participants, their perspectives felt like more of an afterthought and as though they carried less weight. This can be put down to a combination of connection issues, time-constraints, and the difficulty for online participants to disrupt the flow of the conversation taking place in the physical room. Throughout some of the sessions, there were also hands raised by online participants which the moderator never managed to answer. When perspectives are being gathered on the development of targets for a global framework on adaptation, it is important to think about what these little omissions mean over the course of eight workshops and how the disparity between online and offline negotiations might affect future global agreements in the future.

Where next for online research

Covid-19 has changed the way many events take place, enabling more people to conduct research through digital means. At this point it is vital to reflect on the various opportunities, challenges and impacts of digital research. Conducting research online has many positives. In the context of the climate crisis, it allows us to continue our work without racking up airmiles. With increased financial constraints and the contraction of university budgets, it also offers an affordable alternative to attending in person. For those who are time-poor due to added challenges such as child-care, it may also provide the only opportunity to participate. However, researchers need to be attuned to the limitations of online ethnography. In the context of global agreement making, this includes recognising the power dynamics underlying online participation and the drawbacks of partial findings. Digital ethnography provides a meaningful tool through which to conduct vital research, but we need to think seriously about how we can ensure its effectiveness.

Aishath Green is Research Manager at the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction on the project Accountable Adaptation.

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLRDR

Floods in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil: chronicle of a tragedy

By Alisson Droppa and Lara Nasi, on 14 June 2024

Here we write about the greatest climate tragedy ever experienced in Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Southern Brazil. In many ways, it may be the biggest Brazilian climate tragedy. A survey carried out by Folha de S. Paulo newspaper shows that the number of 600 thousand people displaced by the flood is the highest in relation to all other disasters provoked by rains in Brazil. Until the end of May, there are 169 dead people, 50 missing ones and more than 800 injured. In total, it is estimated that 2,3 million have been affected.

Maybe this tragedy is the one that finally reinforces the idea that this scenario is a result of climate change, putting the clime in the agenda of media and social media. But with the destruction caused by the flood that affected 450 of the state’s 497 municipalities and left entire cities in ruins, the questions remains: could it be any different?

The abandonment of a protection system

Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, had 46 of its 96 neighborhoods affected. It is from the capital, which is still under water in many places, including downtown, that, while we write, we found clues that the outcome of this story could have been different.

In the 70’s, Porto Alegre built an important and robust system of protection to avoid other floods like the one in 1941, so far the biggest ever registered. It included 42 miles of earth dikes, a 1.6 miles wall along Mauá avenue, on the banks of Guaíba River, 14 floodgates along the wall and several pump houses spread throughout the city.

In 2017 the city hall decided to extinguish the municipal body responsible for its maintenance, the storm sewer department, to cut costs. The dispersion of responsibilities and technical knowledge has hidden a maze of faults and disinvestment that have been occurring over time and that became visible just when the system should fulfill its function. Instead, it collapsed. Many floodgates were stuck and there were several other structural problems that put Porto Alegre, literally, under water.

If the tragedy is announced, everyone knows prevention would be better

We cannot say that what is happening in Rio Grande do Sul is a big surprise, at least not for government officials and scientists. On the one hand, there were many studies indicating that, with global warming increase, Rio Grande do Sul would experience major floodings (and the state actually had a big and concerning flood in September 2023 that destroyed many cities). This data had been pointed out, for example, in the Brazil 2040 study, commissioned by federal government, during Dilma Roussef’s presidency, but was considered alarmist and then was shelved.

On the other hand, knowing about this and other studies and warnings, government officials preferred to ignore it and keep with the agenda of shrinking the state and handing it over for the private sector. Governor Eduardo Leite stated that he was aware of the warnings, but his priority was the fiscal agenda. Rio Grande do Sul even commissioned a disaster prevention plan in 2017, as reported by Agência Pública, that never got off the ground. There is also a decline in investment in Civil Defense, for example, as well as in the project to manage responses to natural disasters.

Moreover, Eduardo Leite’s administration had changed almost 500 points of Rio Grande do Sul Environmental Code, dismantling environmental protection framework in the state. It is not something just local. In Brazil, during Bolsonaro’s presidency, there was open incentive to deforestation, without any constraint.

The legacy is painful for those who live the results of environmental tragedy. And it persists. Lula’s administration, which has been acting to minimize the tragedy with programs and emergency social policies, needs to deal with misinformation and denialism that disturb even aid for those affected by the tragedy, as well as intend to minimize the presence of State as an articulator of both prevention and solutions to the crisis. The ode to privatisaion and the disassembling of State persists in the legislature. During the crisis in Rio Grande do Sul, federal deputies put forward the so-call “Destruction Package”, a set of at least 25 bills against environmental legislation already established.

The path, therefore, we know will be long. If there is no change in the political logic capable to stop environmental destruction and redirect public investment in preventing disasters and tragedies resulting from climate change, we know this is just a beginning of a new cycle which is not encouraging at al.

Help to rebuild RS

Trade Unions, social movements and civil society are intensely helping to rebuild the state and to assist affected families. Even though, after more than a month with many cities under the water, Rio Grande do Sul is still in the emergency phase of the tragedy. The upcoming ones are going to be long and costly. Human losses are irreparable and material ones are estimated in billions of reais. Here is how to donate:

Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem-Terra (MST)

MST is organizing a campaign to support rural populations affected, smallholder family farmers. Read more information here.

Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem-Teto (MTST)

Solidarity Kitchens

MTST, which already has a solidarity kitchen in Porto Alegre, now needs help to

increase production and be able to assist more people in this calamity. Read more information.

PIX: enchentes@apoia-se

Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT-RS)

CUT Trade Union is running a solidarity emergency campaign to help families affected by the floods. Read more information.

For donations:

– Cresol Bank (133)

– Agency 5607

– account: 18.735-6

– CNPJ: 60.563.731/0014-91

– PIX: 51996410961

– Donations of products and merchandise

This kind of donation is tax exempt. The donor simply needs to take the goods to a carrier of their choice and indicate as recipient of the donation the CNPJ of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs: CNPJ: 00.394.536/ 0006-43.

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Launch of Gender Action Plan (GAP) to support Sendai Framework for DRR

By Zahra Khan, on 16 May 2024

On the 18th of March 2024, at the Commission for the Status of Women (CSW) 68 in NYC, the Gender Action Plan (GAP) to support the Sendai Framework was launched. I was very happy to be sitting in the room that was very full, especially of women and representatives from different delegations and UN agencies. It was a celebratory occasion marking an important milestone in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and the beginning of the discussion to implement the plan collectively over the next 6 years.

UN Women, the UN Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA), and UNDRR were all present to provide some insight. UN Women started by commenting that since the launch of the Sendai Framework in 2015, they have been working together to link gender equality in resilience, and the role that gender inequality plays in disaster related risk – the most impacted by disasters are those marginalised such as women, the elderly, and the youth. Last year marked the halfway point of the Sendai framework, where parties renewed their commitment and agreed to close the gender gap in DRR and resilience with the GAP providing a clear pathway in closing that gap. It addresses the disproportionate effect of disaster on women and girls and emphasises the need to involve and increase women participation at government level so they can influence and implement policy.

Climate change is deepening, and over 12000 climate disasters have been recorded since 1970 resulting in tremendous economic and human loss. There’s only six years left of the Sendai framework to reverse this bleak trajectory, but by working together this can be done. Take, for example, the hole in the Ozone layer – 35 years ago countries came together to combat the impact and now it is currently healing. The GAP was built by 70 countries and 500 non-governmental stakeholders, highlighting the need to scale up gender responsive DRR to get back on track for the 2030 agenda, and increasing efforts in supporting women in small island developing states (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs) to access DRR offices.

The UNFPA echoed these sentiments; the GAP integrates a gender lens in all DRR practices and is structured around the 4 fragilities in the Sendai framework to accelerate impact by governments. Gender based violence (GBV) was also mentioned as this increases in a disaster context and we need better access to healthcare, reproductive health and family planning services. Gender disaggregated data is still a challenge and we need to strengthen the availability of it to better inform policy. Women are key agents of change, with unique capacities that are indispensable in building resilience. Accessing financing was brought up more than once – where you need funding for women led initiatives in the DRR space.

The UNDRR reiterated that the GAP is a fundamental step in the right direction in mainstreaming gender within DRR and is important because we need to accelerate the progress of the implementation of the Sendai Framework – the costs of disasters are increasing, and we need to manage and control the risks. The GAP cuts across 33 actions over 9 objectives with a consideration for early warnings where women are often left behind. They want to work with countries to implement this and adapt it to turn actions into impact and are currently working on several indicators. The UNDRR hope that in 2030 we can look back on the GAP, having reduced gender inequality and saved lives throughout the world.

The Secretary General’s office was also present and stated a few words. The GAP underlines the resolve of the international community to take decisive action. Policy needs to be risk informed and leverage women leadership – they need to be the centre of policies, planning and decision making especially in resource allocation and deployment. Its full implementation will reduce gender inequality and keep the SDGs promise for all.

Representatives from Malawi, Philippines, Australia, and the stakeholder groups were also in attendance and took the floor to share their insights. Intersectionality with mention of disability was spoken about for the first time. Women with disabilities have different risk exposure and often lose their devices in disasters. Societal inequalities in non-disaster contexts leads to compounded discrimination and the manifestation of GBV which is heightened during disaster response. Malawi has developed training manuals to train women led organisations to implement gender interventions within DRR. The GAP gives confidence to respond to gender issues and ensure that systematic implementation will achieve its objectives, but they are looking for financial support to fully realise these goals.

The Philippines demonstrated a strong intention to commit and reinforce the goals of gender equality, especially in DRR. They also highlighted the need to apply an intersectional lens, shedding light on women and girls in poverty who have different needs and protection in disaster zones. Evacuation shelters should prioritise highly vulnerable women. They have implemented programmes with cash incentives, so people come to the training. They stressed a multisectoral response – governments cannot work alone and need strong collaboration with social welfare services to support internally displaced people. They didn’t want the GAP to be a theoretical exercise, but put into practice, scaling up either gender efforts.

Australia was very active in the consultation and drafting of the GAP with a secure, political commitment for gender responsive and risk informed DRR. They have provided seed funding investment to support the implementation of the GAP. They have increased stakeholder engagement, working in the Pacific region, and assisting partner countries to mobilise domestic resources and eliminate risks to advance the localisation of DRR. They are working to enhance early warning systems across the South Pacific and found that for every $1 invested, they saw a $4 return. They are prioritizing their effort to accelerate the Sendai Framework though measurable actions and sharing good practice.

The representative for the non-governmental stakeholder group was the first to mention that disasters are not natural but are a result of social and economic injustices. There was sense of urgency and determination with a refusal to accept complacency. Half of the population is condemned to powerlessness but it’s a matter of rights and survival – women stabilise economies. The stakeholders which involved many civil societies and women led organisations stand in solidarity to make the GAP a catalyst for lasting change.

The session concluded with questions from the floor where issues of non-paid work and budgets were brought up, the need for accessibility and increased participation of women and girls to drive transformative change. Final remarks stated that the GAP is a vital blueprint towards 2030, to see a substantial decrease in gender related disaster risk and the key priority now is what gets done and we, collectively, need to be the ones that do it.

Zahra Khan is a research and outreach assistant at the GRRIPP project

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s).

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Including local voices in assessing adaptation finance: testing an approach in Nepal

By Jonathan Barnes, on 8 May 2024

Finance is central to international agreements on climate change. Developed countries channel money to developing ones to help fund energy transitions and adaptation to the impacts of climate change reflecting historical responsibility for the climate crisis. Money for adaptation is often spent on building awareness about climate risks, response capacity, and climate-proofing infrastructure. Policymakers have focused on assuring taxpayers that money is being well spent through metrics and management tools. There is a gap in making sure the funds meet the needs of people affected by climate change. This is the adaptation accountability gap.

To explore alternative tools for building local accountability researchers from Practical Action in Nepal and UCL’s Accountable Adaptation Project travelled to Naumile in Karnali Province, Nepal. Our trip was part of a wider research programme exploring how measurement and knowledge practices shape adaptation.

Locally-led adaptation: does the reality match the rhetoric?

Donors, development agencies and multilateral funds and banks have committed to fund more locally-led adaptation (LLA). A top-down model is often less effective and efficient, excluding people from decisions that affect their lives and futures. Facilitating feedback to those channelling finance offers one way to build accountability, making adaptation more responsive to local needs.

The International Institute for Environment and Development, a UK based thinktank, has developed scorecards to record people’s experiences, providing a numeric assessment of project alignment to LLA. This has been piloted in Bangladesh, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Indonesia. These can help recipients to hold donors and intermediaries along the climate finance delivery chain (FDC) to account.

However, these do not meet the needs of the communities consulted. The pilots highlight the need to co-produce local approaches to secure meaningful and honest participation.

Our visit to Naumile was the first step towards this in Nepal. Naumile is a rural area in the Dailekh District of Karnali Province. The village has received money for adaptation projects since 2013 under the National Climate Change Support Programme. This channels money from the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office through national and local government systems to fund locally identified projects. We wanted to understand how people felt about the existing local feedback mechanisms and sought to co-produce an approach for collecting and communicating feedback for this FDC, ultimately to achieve more effective adaptation to climate risks.

How the Naumile user committee want to participate

We met a local committee involved in managing the project in the community hall, next to a storm drain being built by the project. This group oversees project implementation and monitoring and evaluation. It consists of nine democratically elected men and women. The community members insisted any feedback and accountability mechanism must be deliberative and democratic. They were clear and unanimous that people should not be consulted individually, and that everybody should get their opportunity to speak – ideally directly to donors. Existing accountability processes such as public hearings and direct dialogues with local government are seen to be working well and could be built on for adaptation. The user committee participates in a monitoring and evaluation subcommittee that provides feedback this way, and the consultation suggested strengthening existing mechanisms. The committee also rejected quantification of their views. They felt this couldn’t capture the lived experience and can misrepresent their opinions.

Key features of the approach:

- Build on existing feedback and accountability mechanisms; public hearings, grievance procedures and suggestion boxes

- Democratic and deliberative focus groups, mediated by local facilitator. Everyone must be heard and opinions must not be reduced to numerical values

- Direct dialogue with government and donor representatives

- Outside support is welcome for facilitation, but the process must be transparent and result in tangible change and feedback from others.

Time and power

Members of the user committee are happy to share views but want more transparency about how their feedback is used. Donors and intermediary organisations claim to be willing to respond to local inputs, but this has not translated into tangible changes. Without more feedback on decisions made in response to local consultations the committee members questioned if it is worth their time to keep participating. People have busy lives. Any accountability mechanism must work around busy periods such as harvest and the rainy season.

We still don’t know whether people would be comfortable sharing their honest opinions about projects, even with a local facilitator. The incentives to maintain good relationships are clear. This could undermine the quality of feedback, and mask challenges. Those we spoke to reassured us that this would not be a problem, in turn highlighting a complex issue relating to the representation of the committee. Does this group represent everybody in the community? How does it intersect with local power dynamics? Members may have vested interests to report favourably, not reflecting wider community feeling. More generally, this governance structure might align well with the principles for LLA whilst consolidating power and resource access amongst a portion of the community.

Way forward: from feedback to accountability

We have gained insights about collecting community level feedback to enhance accountability for LLA in Nepal. The co-produced method in Naumile needs tailoring for other parts of Nepal and researchers must be attentive to who’s views are included.

Bigger questions about accountability in adaptation emerged. Whilst people we consulted opposed the quantification of their views, the project’s impact is quantified in other ways. By rejecting the international language of numbers and metrics, the people of Naumile are marking their feedback as qualitatively different, rendering it difficult to translate insights to national or international spaces.

Taking a wider perspective, if local recipients report a project is working well, does that equate to accountability? Accountability is more than generating information or transparency, it requires that actors in the FDC act on feedback, leading to meaningful change. Being accountable to those most affected by the climate crisis means long-term change in the face of multiple and cascading risks. Individual success stories must lead to wider learning and behaviour change if we are to achieve this.

Jonathan is a critical human geographer interested in environmental policy, social transitions and sustainable finance. His work draws on post-structural theory to explore the effectiveness and equity of climate finance. He is a Research Fellow in Climate Change Adaptation on a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship, exploring the politics of knowledge in climate change adaptation. His PhD research, carried out at the London School of Economics (LSE), explored Green Climate Fund (GCF) project development in South Africa through a climate justice lens.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s).

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Reflections on 2024 Noto earthquake: do we need to pay more attention to the ‘human’ element of disaster?

By Miwako Kitamura, on 3 May 2024

A 7.5 magnitude earthquake struck Noto Peninsula of Japan on New Year’s Day in 2024. Family members had come home to celebrate the New Year when the earthquake hit. Japan has a high level of awareness on disaster preparedness and mitigation. Despite this, more than 240 people lost their lives, 60,000 buildings were damaged and 25,000 people had to be evacuated from their homes. It is important to note that the deaths were caused by the earthquake where several buildings, especially the old structures collapsed. The new year’s earthquake also caused a tsunami, which arrived only a few minutes after the earthquake. However, the majority of people died from earthquakes, with only two people killed by the tsunami, which shows high awareness about tsunami preparedness among the general population, compared to the earthquakes. This shows more work needs to be done on earthquake preparedness in Japan, beyond a focus on developing and investing in resilient infrastructure.

In this short blog, we will shed some light on the experiences of people who are managing the evacuation centres, especially those evacuation centres that are led by the community. We will examine the current situation by putting gender and communities at the centre of our analysis.

Although there are many government run evacuation centres, there are also several community-run evacuation centres. In Japan, community-led shelters are commonly referred to as “voluntary shelters.” Leaders of these shelters typically include local community figures and temple and shrine heads, and, as observed during the Great East Japan Earthquake, leaders of traditional performing arts groups have frequently assumed these roles. Importantly, the foremost consideration for these community-oriented shelters is their trustworthiness. What we found was that due to the gender division of labour, which is still strongly present in Japanese society, taking care of the people in the evacuation centres becomes and remains the responsibility of women, including cooking, cleaning, and caretaking roles.

One important thing to note here is that these women, often wives/daughters/daughters-in-law, of the community leaders who automatically become the caretaker of the entire community in the times of crisis, are themselves the survivors of such events. However, they need to sacrifice their own needs and look after others. With harmony being the central key in Japanese social organisation, speaking of their own needs is seen as being selfish. Hence, no one is willing to do that: they would rather suffer than to bear the consequences of social stigma. This creates an environment where these women who are responsible for running the evacuation are often double victims: victims of the disaster and also the victims of post-disaster responsibilities.

The person responsible for one of the evacuation centres we visited said it is comparatively manageable soon after the disaster as we only need to manage their immediate needs and there are more volunteers. However, as the time passes, people would like their normal life to return, which means a need for proper meals, proper sanitation, healthcare services, better accommodation and so on. The volunteers often go back to everyday life and the support from the government often dries out in about three months but the needs of those who are left behind – still in evacuation centres for various reasons – remain or they need even further support. Hence, taking care of the evacuees becomes a bigger responsibility, which needs to be factored into the discussions around disaster mitigation.

As evidenced during fieldwork and engagement activities in the communities affected by the earthquake in Noto, there are key local contexts and practices which must be appreciated and factored into future preparedness and response activities for disaster risk reduction. Discussions with stakeholders and local leaders for example highlighted the central value of community involvement in shaping and informing responses to disasters.

While it was reported that affected communities following the earthquake were more reserved in their engagement with the national government, they engaged readily and openly when responses were designed and driven by local communities, as evidenced by the creation of these community evacuation centres. These observations on the need to centre community involvement in disaster risk reduction and response are further substantiated by existing evidence from another disaster case study in Japan— the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami which underscored a similar significance regarding the importance of contextually-appropriate and community-supported activities for disaster risk reduction and preparedness and response to events including earthquakes and tsunamis in regionally and geographically diverse countries, like Japan.

Our visit to the Noto Peninsula also revealed important observations and considerations on local understandings of leadership in disaster contexts, and how entrenched and gendered understandings of what constitute leadership can serve as a barrier to further vital involvement and participation of communities during events like earthquakes. This was made apparent during discussions with female local leaders in Noto who had noted and reflected on how, despite their extensive involvement in disaster response and support activities, they did not consider themselves to be ‘leaders’ in these disaster contexts. Instead, many of their channels of leadership and support, including organising community efforts, food provision and emotional support had been regarded as traditionally ‘female’ associated practices and expectations rather than leadership roles during emergencies like earthquakes.

Again, this underscores the need to integrate local thinking and contexts in working to improve and promote local leadership during disasters in Japan by including gender frameworks to uncover how existing power dynamics and divisions of labour produce inequitable understandings of leadership, and where possible and when contextually-appropriate, to engage and work with these local communities to promote and centre diverse profiles and practices of disaster leadership and engagement of women and gender-diverse communities.

Our observations from these fieldwork activities investigating gender and women’s leadership in the Noto Peninsula also hold broader importance for the fields of disaster risk reduction and global health beyond preparing for and responding to earthquakes. Japan continues to be vulnerable to a broad scope of public health risks including earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic activity, floods, typhoons and the climate change emergency. Despite ongoing disaster and resilience planning, there remains a critical need for the ongoing consideration and integration of gender-focused and community-centred participation and leadership activities as revealed during these fieldwork engagements to ensure that future responses and recovery to these events are both sustainable and equitable.

Co-authors

Dr Miwako Kitamura is an Assistant Professor at the International Research Institute of Disaster Science at Tohoku University

Dr Anawat Suppasri is an Associate Professor at the International Research Institute of Disaster Science at Tohoku University

Ms Hayley Leggett is a PhD candidate at the School of Engineering at Tohoku University

Dr Anna Matsukawa is an Associate Professor at University of Hyogo

Dr Stephen Roberts is Lecturer in Global Health at the Institute for Global Health at University College London

Dr Punam Yadav is an Associate Professor at the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction at University College London

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s).

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Was the flood disaster in Oman avoidable?

By Salma Al-Zadjali, on 25 April 2024

On April 14, a severe flash flood invaded Oman from an extreme precipitation event that lasted until April 17. The highest rainfall record over the entire period was 302mm, while the peak hourly record reached 180.2mm. This weather event is not an extraordinary case considering the topography of Oman represented by the lofty Al Hajar mountains. Advection from hot and cold air masses during this transitional season and moisture flow from the surrounding water basins are all a recipe for severe thunderstorms, especially when combined with an external trigger such as surface low pressures and extended upper level-troughs. However, the interaction of humans with natural hazards created susceptibility to a disaster. Up to April 18, 21 people were found dead, including 11 pupils and infants. The final number of lost bodies is not yet confirmed. At least 1200 people including kids were trapped in schools and buses rescued by the Civil defence. Many people were isolated on the road or in their houses as flash floods invaded their homes and gardens, cutting off transportation links.

The loss was tremendous despite the issuance of warnings and forecasts. The root cause of this disaster was inadequate decision-making which led to the loss of life and enormous damages by increasing the risks, exposure, and vulnerability. Communities live on the floodplain and the flood-prone areas in the valleys (locally known as Wadis) that connect the mountains and the coastal plain. Intensive floodplain land use and a poor urban planning system aggravated flooding incidence. However, no statistics are available to the public indicating the extent and nature of property damage. The absence of a sufficient drainage system amplified the calamity during this case due to the saturation and flooding of the ground from the persistent precipitation.

Are we prepared for more extreme precipitation and intense tropical cyclones in the future as a consequence of climate hazards and cloud seedings operations? How can we mitigate and reduce the risks from extreme future scenarios when the precipitation record is broken?

Call for Action

Day and Fearnley (2015) divided mitigation systems into three main strategies based on when and how actions should be taken: permanent mitigation, responsive mitigation, and anticipatory mitigation. Their study showed how important it is to integrate and coordinate these three strategies, which also need to be tested to see how well and resilient they work. For these strategies to work well together, paying close attention to how they affect each other is essential. The most important thing to consider is how the vulnerable population understands the decision-making processes, how they react to the warning messages regarding their awareness, and what they expect these strategies to do. For example, the limited ability of permanent mitigation strategies to deal with rare hazards under poor responsive and anticipatory strategies leads to disastrous results. The historical record was ignored during the northeast Japan earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011, despite the high standards of permanent mitigation measures. The same thing could happen under irresponsive actions toward the issued warnings. The schools and workplaces would have been moved online, and the announcement should have been made at least 48 hours before the approach of the significant weather cases.

Successful mitigation systems require four key components: a map of the hazards, an early warning system, a control structure and non-structure measures, and regional planning and development (Wieczorek et al., 2001; Larsen, 2008). Non-structural measures can include reorganising, removing, converting, discouraging, and regulating growth (Wieczorek et al., 2001). For example, preventing, and minimising the redevelopment of areas susceptible to the future hazards. Hazard-prone areas can be utilised as an open space or certain type of farming taking in consideration the relevant factors.

A structural measure could include designing and constructing parallel to the flow direction and constructing multi-story buildings where the second floor can be used for living instead of the first (Kelman, 2001). Unfortunately, no public building census data is available to determine the number of stories in existing buildings in Oman. Other engineering solutions, such as large debris flow impoundment dams and their regular maintenance, could offer some protection even for the alluvial fan regions. More research must be conducted in each watershed to answer specific design questions, including the size of the event for which they should be built (Larsen, 2008).

Although the warning system does not prevent property damage, it protects lives by predicting flood-prone areas. It relies on radar, ground, and upper-air observations, as well as a robust model to identify the thresholds that trigger flood risk for each place with a rapid and practical link between Ministries of education, higher education, labour, civil defence, police, and the relevant authorities. Using general flash flood forecasts for fear of false alarms reduces the credibility and practicability of the warning system. On the other hand, the use and value of a warning are inversely proportional to the size of the geographical area covered by the warning (Larsen, 2008).

Regional planning and policy formulation need to involve multidisciplinary experts. For example, developing a flood hazard management policy requires technical expertise, public education and awareness, and good communication between scientists, policymakers, and politicians. Local communities should be involved alongside physical and social scientists. Post-event decision-making about recovery and reconstruction involves an exemplary dialogue between the government, experts, and the local population. Different options must be considered, such as balancing flood risk reduction against loss of livelihood and social considerations, and a compromise must be reached between the different groups. This measure guarantees that local voices and narratives are heard, ensuring resilience can only be accomplished by appreciating human livelihoods.

With the increasing responsibilities and capability of efficiently responding to warnings, the study of how decision-makers and people receive and react to a warning has become essential to warning design. Educational programmes should be developed to increase familiarity with the warnings and the appropriate response (see Towards the “perfect” weather warning from the WMO), which is also emphasised in Target G of the Sendai Framework to “Substantially increase the availability of and access to multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk information and assessments to people by 2030”.

There is a need to develop disaster risk reduction strategies and systems that allow for the large uncertainties in the region’s hazard frequency-intensity distributions. No one can deny the complexity of Oman’s topography or the flood risks in the Al Hajar mountains, but this topography can be a boon if properly engineered and utilised.

Finally, a comprehensive national flood hazard management strategy is urgently required, along with urgent actions to be implemented to tackle the cascading flood risks. With each further delay, the total cost of the bills will go up even further in the future.

Salma Al-Zadjali is a PhD candidate at IRDR, researching decadal climate variability of precipitation in order to assess the feasibility of a cloud seeding project over the Al-Hajar mountains in Oman.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author.

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Is there such a thing as ethical and safe disaster research?

By Mhari Gordon, on 29 February 2024

Disaster ethical and risk considerations have received a growing—and needed—interest in the past few years. This has led to a rise in the likes of calls for ‘Disaster-zone Code of Conduct’ (see Profs Gaillard and Peek in Nature) and disaster discipline-specific ethical standards (see Dr Traczykowski in RADIX).

The ‘Box-Ticking’ Exercise

Ethical and risk considerations have long been treated as peripheral to a research project and only reflected upon when applying for ethics and risk assessment approval from a university – with such procedures often viewed as an ‘obstacle’. Common complaints are centred around the time it takes to fill in various forms and providing documentation, as well as the length of the review process. The approval procedures have largely been derived from medical and physical sciences using quantitative methods and analysis. As such, their appropriateness to disaster studies, as well as being treated as a tick-box mentality, has been critiqued by disaster and other social science researchers. There is a need for ethical and risk considerations to be reflected and acted upon throughout the entirety of a project.

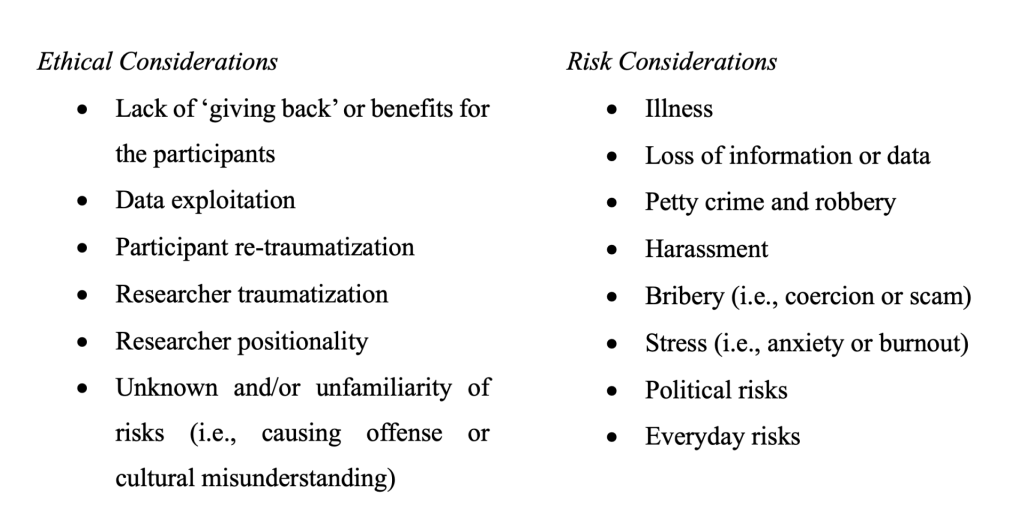

Disaster Ethical and Risk Considerations

Many of the ethical and risk considerations and procedures used in disaster studies have been drawn from lessons and practices in the humanitarian and global health sector. Such sectors tend to operate in different contexts and landscapes than disaster research. A lot of the time, disaster researchers are not working in such controlled spaces or in teams, like in humanitarian responses (see Dr Smirl’s book Spaces of Aid: How Cars, Compounds and Hotels Shape Humanitarianism). Therefore, it is important to reflect and develop ethical and risk considerations which are representative of disaster research.

‘Outsourcing’ of Ethics and Risk

A common mitigation strategy and ‘best practice’ used to overcome certain ethical and risk considerations is to collaborate with local partners or research assistants. For example, having locals conduct surveys or hiring a local person as a driver or translator. Whilst this can contribute great value and legitimacy to a project, it can also (unintentionally) create situations and conditions which may place such individuals in precarious situations (see Mena and Hilhorst’s paper on ethical considerations in disaster and conflict-affected areas or Redfield’s (2012) paper on Médecins Sans Frontières efforts to decolonize). For example, locals being asked by authorities to share information about the project(s) or non-local researchers. As such, this can potentially transfer the onus of ethics and risk from the principal researcher and their institute to their local counterparts.

To assess ethical and risk considerations effectively, research plans and actions should be reviewed and revised during the entirety of the project—with a focus on the relation with others including local people, partners, and organisations/institutions.

Future of ethical and risk considerations in disaster studies

There is a growing recognition within the disaster studies that there is a need to engage in more ethically and risk aware research practices. Some scholars are using and encouraging the use of more reflexive and creative methodologies and methods – stimulating a move away from the historically popular quantitative methods and fully-objective approaches. Multi-media use in combination with more traditional methods, such as interviews, have been increasingly used in disaster research and publications. For example, using playdough or body-mapping workshops and interviews to describe experiences of floods in South Africa (see Emily Ragus) or creating novella-based creative workshops and interviews with Puerto Rican families about their experiences of recovery from Hurricane Maria (see Dr Gemma Sou).

Whilst certain methods may not be new, per-se, the reflexive manner to which they have been applied to disaster studies can be argued to be novel and showing a shift in general approaches. Such approaches will – of course – have their set of ethical and risk considerations, however, these types of approaches have the potential to be more in-tune with such considerations for the researcher, participants, and wider populations. The growing momentum of such approaches is recognised in the likes of an increasing number of signatories to the RADIX Disaster Manifesto and Accord, as well as an upcoming special issue in the popular disaster journal, Disaster Prevention and Management, on ‘Creative, Reflexive, and Critical Methodologies in Disaster Studies’ with a focus on ethical dimensions and power imbalances.

As disasters continue to be experienced and researched globally, it is important that continued efforts are made to further integrate ethical and risk considerations in disaster research. Collaborating and sharing experiences, lessons, and reflections with other disaster researchers and practitioners will be significant in working towards keeping everyone safe in the research of preventing, experiencing, and recovering from disasters.

Mhari Gordon is a PhD student at the UCL Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction. Her research focuses on displaced populations and their experiences of risk, disasters, and warnings, which is funded by the UCL Warning Research Centre. During her PhD, she has been active in other research projects, teaching, and volunteering. Mhari would like to gratefully acknowledge UCL IRDR for funding the expenses to attend the NEEDS 2023 Conference.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author.

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Mapping the world’s largest hidden resource

By Mohammad Shamsudduha, on 15 February 2024

Water sustains life and livelihoods. It is intrinsically linked to all aspects of life from maintaining a healthy life, growing food, and economic development to supporting ecosystems services and biodiversity. Groundwater—water that is found underneath the earth’s surface in cracks and pores of sediments and rocks—stores almost 99% of all liquid freshwater on Earth. Globally, it is a vital resource that provides drinking water to billions of individuals and supplies nearly half of all freshwaters used for irrigation to produce crops. But are we using it sustainably?

Abstraction

Groundwater is dug out of subsurface aquifers by wells and boreholes, or it comes out naturally through cracks of rocks via springs. Today, about 2.5 billion people depend on groundwater to satisfy their drinking water needs, and a third of the world’s irrigation water supply comes from groundwater. It plays a crucial role in supplying drinking water during disasters such as floods and droughts when surface water is too polluted or absent. Despite its important role in our society, the hidden nature of groundwater often means it is underappreciated and underrepresented in our global and national policies as well as public awareness. Consequently, A hidden natural resource that is out of sight is also out of mind.

Some countries (e.g., Bangladesh) are primarily dependent on groundwater for everything they do from crop production to the generation of energy. Other countries like the UK use surface water alongside groundwater to meet their daily water needs; some countries (e.g., Qatar, Malta) in the world are almost entirely dependent on groundwater resources. Because of its general purity, groundwater is also heavily used in the industrial sector.

Monitoring

Despite our heavy reliance on it, there is a lack of groundwater monitoring across the world. Monitoring of groundwater resources, both quality and quantity, is patchy and uneven. Developed countries like Australia, France and USA have very good infrastructure for monitoring groundwater. Monitoring is little or absent in many low- and medium-income countries around the world. There are some exceptions as some countries in the global south such as Bangladesh, India and Iran do have good monitoring networks of groundwater levels.

Groundwater storage changes are normally measured at an observation borehole or well manually with a whistle attached to a measuring tape, so when it comes into contact with water, it makes a sound. It can be also monitored by sophisticated automated data loggers. Groundwater can be monitored indirectly using computer models and, remotely at large spatial scales, by earth observation satellites such as the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) twin satellite mission. Models and satellite data have shown that groundwater levels are falling in many aquifers around the world because of over-abstraction and changes in land-use and climate change. However, due to lack of global-scale monitoring of groundwater levels, mapping of world’s aquifers has not been done at the scale of its use and management.

Current research

New research published in Nature (Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally) led by researchers from UCL, University of California at Santa Barbara and ETH Zürich has analysed groundwater-level measurements taken over the last two decades from 170,000 wells in about 1,700 aquifer systems. This is the first study that has mapped trends in groundwater levels using ground-based data at the global scale in such an unprecedented detail that no computer models or satellite missions have achieved this so far. The mapping of aquifers in more than 40 countries has revealed great details of the spatiotemporal dynamics in groundwater storage change.

The study has found that groundwater levels are declining by more than 10 cm per year in 36% of the monitored aquifer systems. It has also reported rapid declines of more than 50 cm per year in 12% of the aquifer systems with the most severe declines observed in cultivated lands in dry climates. Many aquifers in Iran, Chile, Mexico, and the USA are declining rapidly in the 21st century. Sustained groundwater depletion can cause seawater intrusion in coastal areas, land subsidence, streamflow depletion and wells running dry when pumping of groundwater is high and the natural rates of aquifer’s replenishment are smaller than the withdrawals rates of water. Depletion of aquifers can seriously affect water and food security, and natural functioning of wetlands and rivers, and more critically, access to clean and convenient freshwater for all.

The study has also shown that groundwater levels have recovered or been recovering in some previously depleted aquifers around the world. For example, aquifers in Spain, Thailand as well as in some parts of the USA have recovered from being depleted over a period of time. These finding are new and can shed light on the scale of groundwater depletion problem that was not possible to visualise from global-scale computer models or satellites. This research highlights some cases of recovery where groundwater-level declines were reversed by interventions such as policy changes, inter-basin water transfers or nature-based but technologically-aided solutions such as managed aquifer recharge. For example, Bangkok in Thailand saw a reversal of groundwater-level decline from the 1980s and 1990s following the implementation of regulations designed to reduce groundwater pumping in the recent decades.

Groundwater is considered to be more resilient to climate change compared to surface water. Experts say climate adaptation means better water management. Globally, the awareness of groundwater is growing very fast. It has been especially highlighted in the latest IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, the UN World Water Development Report 2022 (Groundwater: Making the invisible visible), the UN Water Conference 2023, and more recently in COP28 (Drive Water Up the Agenda). Groundwater should be prioritised in climate and natural hazard and disaster risk reduction strategies, short-term humanitarian crisis response and long-term sustainable development action.

Dr Mohammad Shamsudduha “Shams” is an Associate Professor in IRDR with a research focus on water risks to public health, sustainable development, and climate resilience.

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author.

Read more IRDR Blogs

Follow IRDR on Twitter @UCLIRDR

Close

Close