8 June 2012

By Chris Husbands

Social mobility is news. At the Sutton Trust/Carnegie Foundation London social mobility summit last month, leading politicians from all three parties lined up to decry Britain as a country with lower levels of social mobility than almost any other advanced society.

Michael Gove, the Conservative education secretary, has said before that domination of positions of leadership and influence by those educated at private school results in ‘stratification and segregation [that] are morally indefensible’. Nick Clegg, the Lib Dem deputy prime minister, has bemoaned the failings of a society “that still says where you are born, and who you are born to, matters for the rest of your life” and Labour leader Ed Miliband declares that “the doors of opportunity are open much wider for a wealthy and privileged few than they are for the many”.

Political consensus rarely holds for long and this is no exception. Proposed solutions spin off rapidly into quite different policy prescriptions. For Gove, the key is for all schools to match the best, so as to expand the opportunities available to children and young people. For him, the key is curriculum and assessment reform so that all schools mimic the best practice in independent – and, he is careful to say – state schools.

For the deputy prime minister, “social mobility is all about creating a truly level playing field, and a fair race”, so that, for example, universities recruit students on the basis of “objective potential… not purely on previous attainment”. For Clegg, therefore, the pupil premium, which offers schools additional resources for the education of the most disadvantaged children is key, in order to bring more children to the starting line of the “fair race”. For him, it is misleading to conflate social mobility with inequality.

For Ed Miliband, the solution is different again: it is to “improve opportunities for everyone, including those who don’t go to university. He argues that “we must reject the snobbery that says the only route to social mobility runs through university”.

These disagreements are important in policy terms, but they also demonstrate something else: when we think about social mobility, people “see” many different things. This leads to very different assumptions about what the problem is and what the policy solution should be. Some policy approaches – and Nick Clegg uses the image explicitly – talk about “levelling the playing field”. The argument is put by the Cabinet Office 2011 Social Mobility Strategy: “For any given level of skill and ambition, regardless of an individual’s background, everyone should have an equal chance of getting the job they want or reaching a higher income bracket.” The job of government is to try to ensure that all can participate in such a race.

These disagreements are important in policy terms, but they also demonstrate something else: when we think about social mobility, people “see” many different things. This leads to very different assumptions about what the problem is and what the policy solution should be. Some policy approaches – and Nick Clegg uses the image explicitly – talk about “levelling the playing field”. The argument is put by the Cabinet Office 2011 Social Mobility Strategy: “For any given level of skill and ambition, regardless of an individual’s background, everyone should have an equal chance of getting the job they want or reaching a higher income bracket.” The job of government is to try to ensure that all can participate in such a race.

For others, the issue is about access to the top – the elevator – opening access to the most prestigious universities, the most prestigious jobs and the most influential positions in society. This “elevator” model focuses on the fact that – again in the words of the Cabinet Office paper – “Only 7% of the population attend independent schools, but the privately educated account for more than half of the top level of most professions, including 70% of high court judges, 54% of top journalists and 54% of chief executive officers of FTSE 100 companies”, and considers how these positions can be opened up. This point of view emphasises opening access to “elite” universities and schools – perhaps expanding grammar schools, although the evidence for grammar schools as motors of social mobility is extra-ordinarily thin on the ground.

For others, the issue is about access to the top – the elevator – opening access to the most prestigious universities, the most prestigious jobs and the most influential positions in society. This “elevator” model focuses on the fact that – again in the words of the Cabinet Office paper – “Only 7% of the population attend independent schools, but the privately educated account for more than half of the top level of most professions, including 70% of high court judges, 54% of top journalists and 54% of chief executive officers of FTSE 100 companies”, and considers how these positions can be opened up. This point of view emphasises opening access to “elite” universities and schools – perhaps expanding grammar schools, although the evidence for grammar schools as motors of social mobility is extra-ordinarily thin on the ground.

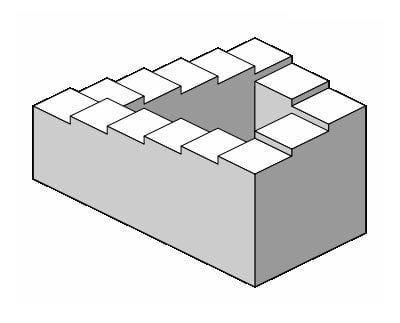

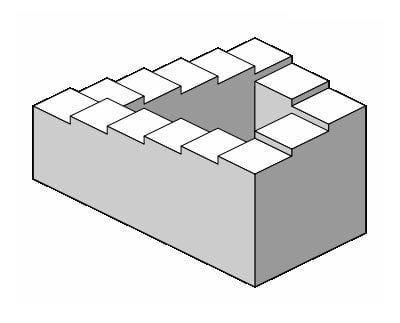

A third, quite different, approach focuses on overall social movement: moving all up by expanding opportunity – the constant upward movement of Escher’s optical illusion, referenced in the picture here. Ed Miliband believes that “social mobility must not be just about changing the odds so that kids from poorer backgrounds make it to university”, but about widening routes and increasing opportunities.

A third, quite different, approach focuses on overall social movement: moving all up by expanding opportunity – the constant upward movement of Escher’s optical illusion, referenced in the picture here. Ed Miliband believes that “social mobility must not be just about changing the odds so that kids from poorer backgrounds make it to university”, but about widening routes and increasing opportunities.

Finally, and most challenging for politicians, is a fourth idea: that social mobility involves movement down the social scale – from more to less influential positions, from rich to poor. The social mobility strategy is explicit on this “relative” social mobility but it is hugely challenging for any government: social mobility is something we all agree on when the opportunities are expanding at the top of the system – as they were in the 30 years after the second world war. Much more difficult in times of constraint.

Finally, and most challenging for politicians, is a fourth idea: that social mobility involves movement down the social scale – from more to less influential positions, from rich to poor. The social mobility strategy is explicit on this “relative” social mobility but it is hugely challenging for any government: social mobility is something we all agree on when the opportunities are expanding at the top of the system – as they were in the 30 years after the second world war. Much more difficult in times of constraint.

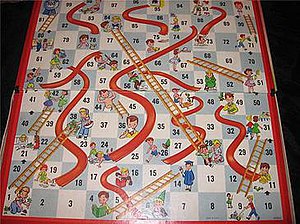

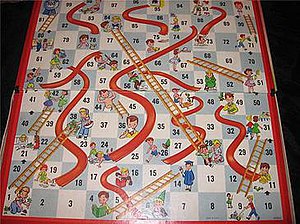

It’s naive to assume that all can agree on an issue as complex and challenging as social mobility which has some powerful implications for the sort of society we are and want to be. But recognising that when we think about it we all ‘see’ different things might help to clarify some of the differences. Level playing fields, elevators, step ladders, snakes and ladders boards: understand the image, understand the point of view.

Picture credits: unlevel playing field, John Kelleher; elevator, Dirk Anger

Close

Close

For others, the issue is about access to the top – the elevator – opening access to the most prestigious universities, the most prestigious jobs and the most influential positions in society. This “elevator” model focuses on the fact that – again in the words of the Cabinet Office paper – “Only 7% of the population attend independent schools, but the privately educated account for more than half of the top level of most professions, including 70% of high court judges, 54% of top journalists and 54% of chief executive officers of FTSE 100 companies”, and considers how these positions can be opened up. This point of view emphasises opening access to “elite” universities and schools – perhaps expanding grammar schools, although the evidence for grammar schools as motors of social mobility is extra-ordinarily thin on the ground.

For others, the issue is about access to the top – the elevator – opening access to the most prestigious universities, the most prestigious jobs and the most influential positions in society. This “elevator” model focuses on the fact that – again in the words of the Cabinet Office paper – “Only 7% of the population attend independent schools, but the privately educated account for more than half of the top level of most professions, including 70% of high court judges, 54% of top journalists and 54% of chief executive officers of FTSE 100 companies”, and considers how these positions can be opened up. This point of view emphasises opening access to “elite” universities and schools – perhaps expanding grammar schools, although the evidence for grammar schools as motors of social mobility is extra-ordinarily thin on the ground.

Finally, and most challenging for politicians, is a fourth idea: that social mobility involves movement down the social scale – from more to less influential positions, from rich to poor. The social mobility strategy is explicit on this “relative” social mobility but it is hugely challenging for any government: social mobility is something we all agree on when the opportunities are expanding at the top of the system – as they were in the 30 years after the second world war. Much more difficult in times of constraint.

Finally, and most challenging for politicians, is a fourth idea: that social mobility involves movement down the social scale – from more to less influential positions, from rich to poor. The social mobility strategy is explicit on this “relative” social mobility but it is hugely challenging for any government: social mobility is something we all agree on when the opportunities are expanding at the top of the system – as they were in the 30 years after the second world war. Much more difficult in times of constraint.