AERA reminds us that education research is part of a genuinely global discourse

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 8 April 2014

Chris Husbands

The annual conference of the American Education Research Association cannot really be described: it has to be experienced. Every year, it attracts almost 20,000 education researchers, not just from North America but from the entire English speaking world, and, in the last decade, increasingly from East Asia. So any individual experience of the conference must still be partial.

For five days, AERA takes over the downtown of a large American city, so the sheer logistics of running the annual conference must be mind boggling. The conference programme is the size of a telephone directory and about as readable: even the app which has been available for the last few years takes some navigation. You have to really know what you are looking for to master the search function, but if you only want to browse it’s difficult – although the AERA2014 app does contain abstracts for the thousands of papers.

In essence, AERA is not one conference but several. AERA is organised into 12 divisions, from administration, organisation and leadership (Division A) through to Education Policy and Politics (Division L), taking in Measurement and Research methodology (Division D) and Learning and Instruction (Division C) with much else besides. Each division runs several parallel sessions at any one time. Then there is the conference of the highlights: the large, set piece lectures and panels led by genuine global stars such as Diane Ravitch (this year on the challenges of quality and equality), Andreas Schleicher (this year on why we should care about international comparisons), Charles Payne (in 2014 on the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil Rights Act) and Linda Darling-Hammond (on issues in the validity of high stakes assessments): their sessions fill the ballrooms of large hotels, standing room only.

Then there is the conference of the post-doctoral researchers, for whom AERA is a grand hiring fair – a good 20-minute performance reporting on your doctorate to a room of perhaps nine people can be instrumental in landing a prestigious position. And of course there is the conference of the corridors: knots of people meeting up to compare experiences of research funding and research policy, to complain about their miserable lot, to plot and to scheme and to gossip, to broker deals and agreements – people who have not seen each other since San Francisco last year and won’t meet again until Chicago next year.

And the range is huge: to deploy some (all too frequently observed) stereotypes, sessions on structural equation modelling led by earnest young think tank econometricians in sharp blazers, sessions on the endless reverberations of race in American education full of lively, disputatious people of colour, sessions on urban school reform led by harassed school superintendents looking for better teacher or school evaluation strategies.

This year’s conference (April 3-7) was in Philadelphia – the conference is always in one of those vast American cities where a wrong turn at one block will take you into parts of town where you’ll come across urban Americans uninterested in the finer points of methodology – and its over-arching theme was “the power of education research for innovation in practice and policy”. Barbara Schneider (Michigan State University), this year’s president, chose to speak about the “college mismatch problem”: why American teenagers from poor backgrounds apply to universities of lower status than their grades could get them into; Ruby Takanishi from the New America Foundation and Rachel Gordon from the University of Illinois looked at what we are learning from universal preschool education.

There are major methodological innovations: the impact of learning analytics on the knowledge base for lifelong learning, what the evidence is saying about recent immigration and its consequences for education. But all this makes it sound too ordered. Opening the telephone directory programme randomly I find ”an Australian perspective on inequality and education”, “blacks, hip-hop and the sociocultural milieu”, “dental school deans’ perception of dental education costs”, ”does teacher and student race congruence help or hinder student engagement in ninth grade science”, “ the common core standards and teacher quality reform” , and “comparing three estimation approaches for the Rasch Testlet model”: and on and on through literally thousands of sessions.

It’s almost impossible to discern trends, though economists seem to be growing in number and influence; ‘big data’ and its promises and pitfalls pre-occupy more people; and even in America – that most inward looking of melting pots – questions of international comparison and globalisation are more than ever in evidence. Being at AERA is a reminder of the similarities and differences between American and English experience in education.

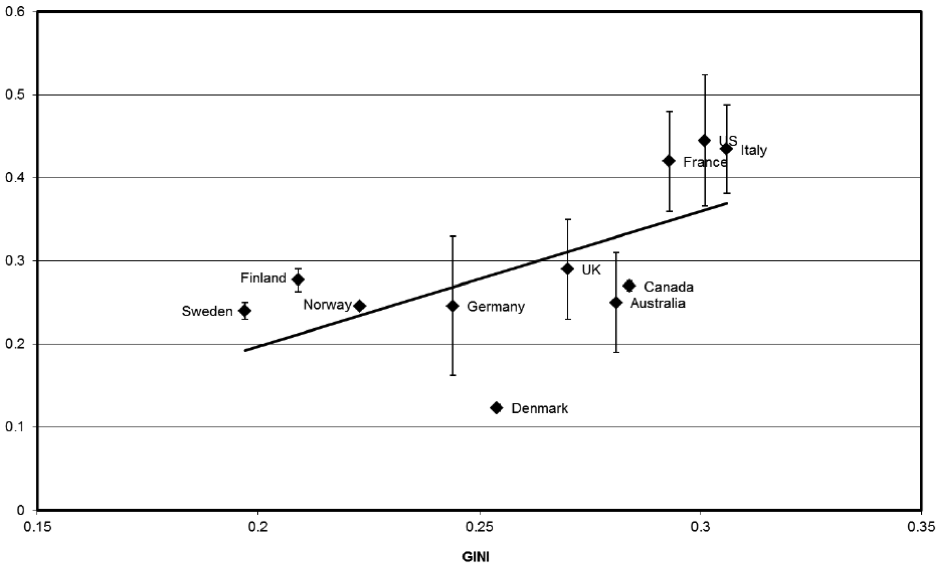

There are some common themes: the relationships between quality and equity, between social structure, education experiences and performance, between the dynamics of research and the dynamics of policy. Others look similar but are really different: academies, for example, are not, in the last analysis, quite the same as charter schools. Others are genuinely different: the American experience of urban school reform is not the English experience; America’s experience in curriculum reform and teacher education has been quite different from England’s.

AERA is always simultaneously disorienting – you inevitably feel you are in the wrong place, that there is a more interesting and important session just around the corner – and energising – thousands of exceptionally able and engaged people enthused about education, and above all reminding us that education research is part of a genuinely global discourse.

Close

Close