TIMSS 2015: do teachers and leaders in England face greater challenges than their international peers?

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 8 November 2017

Toby Greany and Christina Swensson.

This is the third in a series of blogs that delve below the headline findings from the 2015 Trends in International Maths and Science Study (TIMSS)[1]. In this blog, we focus on how the perceptions of teachers and school leaders in England compare with those of their peers in other countries.

Just under 300 English primary and secondary schools took part in TIMSS 2015. The headteachers of these schools, as well as the mathematics and science teachers of randomly selected Year 5 and year 9 classes, were asked to complete a background questionnaire asking their views on a range of issues. Given the way teachers were selected to participate in TIMSS, their responses do not present a representative view of all teachers and headteachers in England. Therefore, we compare the findings from TIMSS with findings from larger national and international surveys where possible.

Summary

Analysis of the TIMSS questionnaire responses indicates that Year 5 and 9 pupils in England are more likely to be taught by teachers who have less experience than their peers in most other countries, but who are nevertheless confident about their skills and knowledge.

The teachers of Year 5 and 9 pupils in England report relatively high levels of access to continuing professional development (CPD) activity, particularly relating to subject content and the curriculum.

Teachers of Year 5 and 9 pupils in England report facing relatively high levels of challenge and low levels of job satisfaction compared to their peers across all participating countries. Perhaps as a result of these challenges, headteachers in England are more likely than headteachers in other countries to report recruitment difficulties.

Experience and confidence

Teachers in England reported fewer years of teaching experience, on average, than the international mean. For example, about a third of Year 5 and 9 pupils in England (35% and 29% respectively) were taught maths by teachers with less than five years’ experience; a far greater proportion than the international mean for each year group (13% and 17% respectively). This finding chimes with the OECD’s Education at a Glance 2017, which reports that teachers in the UK are amongst the youngest internationally.

However, while there is some level of association between greater teaching experience and average pupil achievement across most participating countries (albeit a weak one), this is not consistently the case in England. Despite having less experience overall, teachers in England felt they were well trained and confident in their abilities to teach maths and science. Indeed, a majority of year 5 and 9 pupils in England were being taught by teachers who reported very high or high levels of confidence in the different aspects of teaching maths and science.

Continuing Professional Development (CPD)

Teachers in England reported undertaking relatively high levels of Continuous Professional Development (CPD) compared to their colleagues in other countries, particularly in primary maths. The chart below summarises the areas of professional development undertaken by Year 5 maths teachers.

Aspects of professional development undertaken by year 5 teachers of maths over the past two years and the percentage of pupils taught by these (England with international comparisons, TIMSS 2015)

As can be seen, the majority of Year 5 pupils in England were taught maths by teachers who had received professional development centred on content, curriculum and pedagogy/instruction. These proportions were higher than the means across all participating countries for these aspects, although teachers in some of the highest-performing countries had higher levels of CPD: for example, four out of five Year 5 maths teachers in Singapore and Hong Kong (81% and 83% respectively) had had professional development in the area of pedagogy compared to 68% of teachers in England. A similar picture was reported for maths teachers in Year 9 and for science teachers in both year groups, although the differences between England and the international means were generally smaller. Year 5 teachers in England were considerably less likely to report having had CPD in science than in maths.

The OECD’s 2013 Teaching and Learning International Study (TALIS) captured data from a representative sample of Key Stage 3 teachers in England. It also goes into greater depth on CPD-related issues than TIMSS, for example indicating the amount of time spent on different activities. TALIS highlighted that secondary school teachers in England report high levels of access to CPD, but relatively few days’ CPD per year. Specifically, Key Stage 3 teachers in England receive less than half as much formal CPD as their peers in other participating countries overall (22 days vs 10 days per year).

Perceived challenges

Many aspects of the teaching environment are rated relatively positively by teachers and headteachers in England, when compared with international means. For example, the majority of pupils were taught in schools which teachers reported to be safe and orderly, comparing relatively favourably with most other TIMSS countries. Similarly, pupils in England were much more likely to attend a school that places a very high emphasis on academic success (as rated by their teachers) than their peers in other countries. And in terms of physical conditions and resources, teachers and school leaders in England reported fewer problems than their colleagues in most other countries.

Despite these positives, teachers in England were more likely than their peers in other countries to report facing challenges in their roles (including high workloads, pressure from parents and responding to curriculum changes), and also more likely to report low levels of job satisfaction.

A majority of year 5 and year 9 pupils in England were taught by teachers who reported facing at least ‘some’ challenges. More worryingly, between 12 and 19 per cent of year 5 and year 9 pupils are taught maths by teachers who report facing ‘many’ challenges – more than twice the average rate across all other participating countries.

There is no clear association between the performance of pupils in England and the extent to which their teacher reported facing challenges. However, pupils taught by teachers reporting only ‘few’ challenges tended to perform better than their peers whose teachers reported facing ‘some’ or ‘many’ challenges.

Year 5 and Year 9 pupils in the countries performing at or above England’s level in TIMSS were generally much less likely to be taught by a teacher reporting ‘many’ challenges than was the case in England. In particular, fewer than one in 20 year 5 pupils were taught maths by teachers reporting ‘many’ challenges in eight of these comparator countries, including Finland, Taiwan and Russia, while at year 9 the same is true for six of these countries.

Job satisfaction

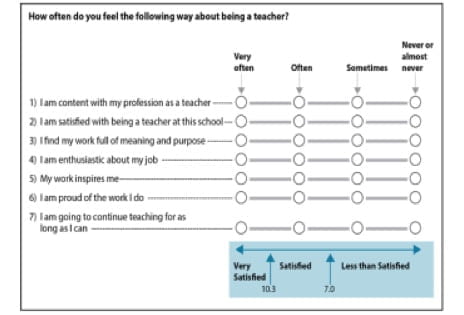

Teachers’ job satisfaction was assessed through a question about the frequency with which teachers perceived feeling certain sentiments about their profession.

Pupils in both Year 5 and Year 9 in England are more likely to be taught by teachers reporting relatively low levels of job satisfaction, compared to their peers in other participating countries, on average.

Whilst the difference is not as stark for Year 5 pupils, this is particularly true for Year 9 pupils. Of the 15 countries that either performed significantly above, or similarly to, England in Year 9 maths, only in Japan are pupils more likely to be taught by teachers reporting low levels of job satisfaction than in England. It should be noted, however, that job satisfaction was lower than the international mean in a number of the highest performing countries, such as Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Recruitment challenges

Headteachers in TIMSS were asked the extent to which their school faced teacher shortages in maths and science. Around half of Year 9 pupils in England were taught in schools whose headteachers perceived some level of shortage in each subject. This figure is similar to the proportions across participating countries as a whole (54% in maths and 52% in science), but is higher than in most countries whose pupils perform similarly or better than pupils in England in these subjects. For example, the chart below shows how England compares on teacher shortages in maths at year 9 against the 15 countries whose pupils perform at or above the level of pupils in England in maths.

Headteachers were also asked about the level of difficulty perceived in filling maths and science vacancies. A quarter of Year 9 pupils in England were taught in schools whose headteachers perceived it was very difficult to recruit maths specialists, while around one in five pupils were taught in schools in which headteachers reported it was very difficult to recruit science specialists. Compared to countries with similar or better performance in TIMSS, headteachers in England reported the greatest challenges with recruitment.

To put these findings into context, it is useful to refer back to the most recent data from the School Workforce Survey for England (November 2016). This survey showed that the teacher vacancy rate remains relatively low and has been around one per cent or below (of all teaching posts) since 2000. There were 920 vacancies for full-time permanent teachers in state-funded schools at the time of the last survey, a rate of 0.3 per cent. In addition, a further 3,280 full-time posts (0.9 per cent) were being temporarily filled by a teacher on a contract of at least one term but less than one year. However, there has been an upwards trend between 2010 and 2015 in the percentage of schools which have at least one advertised vacancy or temporarily-filled post. In 2016, 12.3 per cent of all schools reported having at least one advertised vacancy or temporarily-filled post on the census day in November. For primary schools, it rose from 6.9 per cent in 2015 to 8.9 per cent in 2016, and for secondary schools it rose from 23.0 per cent in 2015 to 27.0 per cent in 2016.

Further information

You can find the full report on England’s performance in TIMSS 2015 here, headlines relating to maths and science performance here, and a blog exploring how pupil attitudes to learning change in relation to achievement here. For more information please see the IEA data tables, which contain data for all countries participating in TIMSS 2015.

[1] For a more detailed report of England’s findings, see the national report. The TIMSS sample design is such that responses from teachers and headteachers provides context for year 5 and year 9 pupils’ results in the TIMSS assessments. Therefore, throughout this blog, teacher responses are presented in terms of the proportion of year 5 or year 9 pupils across the country whose mathematics, science or headteachers agreed, or disagreed to particular statements. Fifty-seven countries participated in TIMSS in 2015. Throughout this blog, the responses of teachers in England are compared to the responses of teachers across all other participating countries.

2 Responses to “TIMSS 2015: do teachers and leaders in England face greater challenges than their international peers?”

- 1

-

2

What does the TIMSS 2015 international encyclopedia tell us about how our curriculum and assessment compare with other countries’? | IOE LONDON BLOG wrote on 1 December 2017:

[…] a blog looking at how teachers and school leaders in England compare with their international peers here. For a detailed breakdown of information available from TIMSS please see the IEA data tables, which […]

Close

Close

Is there any evidence to show whether teachers in England are more likely to report challenges than teachers in e.g. Singapore?