Why We Post: The Anthropology of Social Media

By Laura Haapio-Kirk, on 25 November 2015

The Why We Post project is now moving into its final stages at full speed, gearing up for our public launch on February 29th 2016. On this date we will release the first three of eleven open access books, a free e-course, and an interactive website. You can now register for our course on FutureLearn (English language version) and on UCLeXtend (in Chinese, Hindi, Tamil, Spanish, Italian, Turkish, and Portuguese).

Over 4,300 people have signed up to the course within the first week, sparking discussions around the research which are absolutely fascinating and encouraging to see. Students come from all over the world and range from having a general interest in social media, to being professionally invested in it, from people who have never heard of anthropology, to those who are doing PhDs in the subject. The breadth of learner backgrounds is extraordinary and will no doubt contribute to the vibrancy of the course.

The course consists of a range of learning materials including texts, images, video lectures, and video discussions. There are further materials on our website for learners who want to dig even deeper, including around a hundred films made in the fieldsites and many stories which bring our research to life.

If you want to help us transform global research into global education, then spread the word. Follow the project on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, and tweet with the hashtag #whywepost.

Sign up for the free e-course Why We Post: The Anthropology of Social Media. We can’t wait to meet you!

Promotional film by Cassie Quarless.

Fieldwork is haunting me, thanks to WhatsApp

By Juliano Andrade Spyer, on 3 November 2015

When is it that fieldwork finishes? Thanks to social media, the separation between being in the fieldsite and being in the library is becoming ever more blurred. This is true for anthropologists in general, not just those who study social media, because in many societies platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp have become an important channel of interaction during fieldwork.

In a way, I have carried my fieldsite in Brazil with me back to London. I mostly keep contact through regular exchange of messages with friends from the field. But there is one case that draws me back to the position of fieldworker.

It took me a long time and a lot of effort to be trusted in the village so that people were happy to show me the content that circulates through direct or group messages on WhatsApp. I was particularly happy when one adult woman, who appeared to understood the purpose our research project and resolved to help the research by forwarding the messages she received via WhatsApp to me.

These messages allowed me a glimpse into what this part of Brazilian society – the people now called “the new middle class” – is privately talking about. However, the subjects of the videos exchanged are often distressing. In short, there is a lot of amateur sex and violence (also the subject of this previous post); things that are often not fun to see and that can also carry legal consequences. For instance: the recording of students violently bullying someone is a proof of a crime. This is the kind of material that can land on my phone.

While I could easily tell this informant to stop sending me this content, as a researcher, I feel it would be a pity to close this channel because I am now – thanks to informants like her – in touch with this very private social world. However the constant communication from the fieldsite does pose challenges when it comes to writing-up.

Yesterday I was considering buying a second mobile, so I can leave this one at home and only check the new content every now and then. This way I would be able to distance myself and have more control over this flow of distracting (and occasionally) disturbing content. A new phone would also assure I would retain the many textual conversations and exchanges I had with informants during field work.

But this is just an idea and I am sharing this story here also hoping to hear what others think I should do about this situation. In case you do have something to say, please use the comment area below this blog post.

Many thanks!

Online relationships with strangers can be ‘purer’ than with offline friends

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 26 October 2015

As illustrated in the cartoon ‘On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog’, published by The New Yorker in 1993, the anonymity afforded by online communication raises interesting questions about authenticity and trust. I encountered such concerns at a media workshop where I talked about the high levels of anonymity on Chinese social media platform QQ. One member of the audience asked: “Don’t you think, in a highly mediated and anonymous environment, people are worried about the authenticity of communication?”

From what I can gather from my research, the answer is no.

To address her question I quoted a migrant factory worker called Feige who lived in the factory town where I conducted my fieldwork:

“They [online friends] like you and talk with you because they really like you being you, not because you are rich so that they can borrow money from you, or you are powerful so that they can get a job from you. Here [online] everything is much purer, without power and money involved.”

Feige is a member of many QQ groups and has his own fans who like to hear his opinions on everything. He sees entirely online friendships as ‘purer’ (chun) relationships, since they do not necessitate pragmatic concerns that often feature heavily in offline relationships. For Chinese migrant factory workers like Feige who are often frustrated by their position in society, social media provides new possibilities of sociality which are free from social hierarchy and social discrimination.

Curiously, strangers online also boast a preferable situation in some factory owners’ eyes. Billionaire factory owners in my field site sometimes avoided attending school reunions in fear of requests for financial help from their old classmates but some were happy to talk with online strangers on WeChat to release the stress which they believed could not be displayed to their subordinates and family members.

Ms. Cheng, a wealthy factory owner, told me:

“I feel that nowadays society is very pragmatic. Sometimes I feel very confused and frustrated. Everyone says that the relationship between old classmates is the purest because there are no benefits or interests involved. But in my case, this was not true. After my middle school reunion I had at least six or seven phone calls from people who attended asking for money or other various kinds of help.”

Ms. Cheng dared not attend any further school reunions after her unpleasant experience. However, she found a supportive community by joining a WeChat group where mothers share their experience of raising children. Here she could share her struggles of dealing with her two teenage children. This was a huge support which she felt she could not obtain from her family.

“At home everybody is busy with the factory stuff…but there (WeChat mothers’ group) I am just a mother, not a factory owner. I show my weakness and get a lot of comfort…I don’t know exactly who they are, but I know they are all mothers like me who share the same problems.”

Chinese migrant workers and factory owners probably lie at the two extremes of the wealth spectrum in the industrial China field site, however both appear to be similarly willing to befriend and communicate with strangers online. Here we can witness how relationships which are mediated by technology turn out to be the more ‘authentic’ compared to offline relationships which in many cases are highly mediated (or ‘polluted’ as people say) by factors such as wealth and social status. The cases from China provide us with a new perspective on online relationships. Here ‘anonymity’ by no means refers to the opposite of ‘authenticity’, just as ‘mediation’ by no means suggests less or more ‘authenticity’.

Normativity and social visibility

By Jolynna Sinanan, on 14 October 2015

It has been exactly a year since finishing 15 months of fieldwork in Trinidad. Stories for this blog have moved further and further away from cool stuff that was coming out of the field and living in Trinidad, to the far less exciting but far more intense process of endlessly thinking and rethinking the material and drafting and redrafting articles, book chapters, and books (yes, all plural) from three years of research.

So it’s kind of like experiencing the weather from the ground, how it looks and what it feels like, and then looking at the weather from the sky and how the movement of clouds influences what is happening below. This is what moving from the field to writing feels like, moving from experience and observation to the more abstract.

I have been drawing on my field work in Trinidad for, among other things, edited book chapters on different topics, from emotions and technology to social networks in small communities to social media and ethnography. What has been most striking about working on these condensed pieces of writing and stories from the field is the focus of on the everyday, what is normal in the places we lived and what people in those places take for granted. When we started this project in 2012, we didn’t want to look at isolated, spectacular social media events that seemed to be the thing at the moment, whether it was the Kony 2012 campaign or the Ice Bucket Challenge, although these sort of one off things did appear throughout the research. We were far more interested in normal social media practices and if something came up that everybody talked about, shared or commented on, we were able to contextualise it in everyday relations.

Yet, it is these types of spectacular social media events that attract the most attention. It’s like reading about media in media, which reminds me more of the anxieties of post-modernism and post-post-modernism of the 1990s, where social phenomena is likened to simulacra. From the comparative studies of nine societies (a lot of people) one of our key conclusions is that the use of social media can be generalised as being generally unspectacular. There is a previous blog post on how memes can be a visual means to reinforce social norms and morally acceptable behaviour. Humorous memes also provide a safe and popular way for people to express their views without coming across as too self-righteous or taking oneself too seriously.

Memes are just one example of visual posts, others that show food, outfits, places and events again show the everyday. The more exciting or idealised aspects of the everyday, but the everyday nonetheless. And when the idealised aspects of the everyday are shown, they usually conform to a shared sense of what living the good life means, around consumption and lifestyle, which is particularly important given that for several research participants, especially in the Brazilian, Chinese, Indian and Trinidadian field sites, upward mobility is a genuine aspiration. Again, not surprising that aspirations around lifestyle would be more obvious in the sites in countries that are commonly called ‘developing’ or in ‘the global south’.

The other half of posting (at least visual posts) around social norms is that the audience for these posts are one’s social peers and networks, social media simply makes these forms of expression more visible. Prior to social media, normativity and social visibility have had a long interrelationship and was explored with much more depth by thinkers such as Georg Simmel and more recently Agnes Heller. One of our findings summed up in once sentence is that people care what other people think and say about them, especially if they are from small towns where more people know each other and live alongside one another. There might be social media events that capture participants’ attention for a short time, but by and large, social media usage is, well, normal.

Surveying Social Relationships

By Daniel Miller, on 2 October 2015

One of the chapters of our forthcoming book How the World Changed Social Media, which will be published as an Open Access book by UCL Press in February 2016, describes a survey consisting of 43 questions we asked 1199 respondents (mainly around 100 per fieldsite).

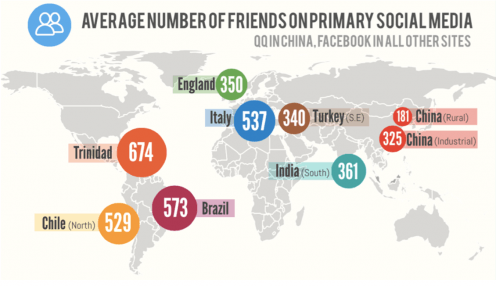

Just occasionally this survey produced results which were commensurate with our general ethnographic data, for example, this chart showing the average number of friends is well matched by what our informants say about how generally sociable they feel people are in the place where they live.

Similarly this figure of whether people use social media to develop new relationships makes sense to us. In some places such as Brazil or Trinidad it is because prior to social media people typically developed friendships through the mechanism of becoming friends with the friends of already established friends or relatives, and this is something that social media lends itself to. By contrast the issue in industrial China is that factory workers, who are constantly shifting from place to place, grow to rely on their online connections as the place for developing friendship, partly because opportunities are quite limited for friendship offline.

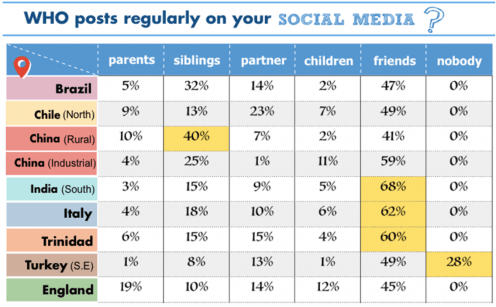

But in other cases the results of this survey are clearly incompatible with what we know from our ethnographies, and we will always favour the authority of 15 months living with a community over a mere survey. It will not be hard for you to spot the problem in the next figure. This is the high number of people in our rural Chinese site who mention siblings as the people who most often post on their walls. The problem is, of course, that given the one family per child policy, most of these young people don’t have siblings. McDonald suggests this is a combination of two factors. Firstly those who do have siblings perhaps share a very close relationship with them. But, this figure also represents a practice in China where it is common to refer to one’s cousins as siblings. It was just one of many examples where we found that our survey could be very misleading unless you had the ethnographic background to understand how and why people had interpreted our questions in a particular and often unpredicted way.

What’s special about social media in small places?

By Razvan Nicolescu, on 19 September 2015

‘Normal friend: ‘Wow, how beautiful you are!’ / Best friend: It’s Shrek on the phone, says he wants his face back.’ Meme shared on Facebook by Comix

From the beginning of my fieldwork I kept thinking about why social media seems to be used so differently in my fieldsite – the Italian town of Grano – compared to other places, such as Rome or Milan. Maybe the most immediate answer is that Grano is a small place!

Indeed, with less than 20,000 inhabitants the town is far smaller than many metropolitan place, and here social relations could be much different than elsewhere. But what does this mean exactly? At the same time, social media is known to be a global technology which promises equal chances to access and utilize online resources to all its users. So, what is the implication of this to the existing social relations? To attempt to answer this, I will given a real-life example from my research.

Salvatore is person who is aware of the immense power he has because of social media, but sometimes he is annoyed that he cannot express himself online in the way that he would like. For example, he would never post photos on Facebook which were taken at parties after drinking too much or behaving ‘stupidly.’ His close friends know this, and they too, would never tag Salvatore in a photo they know he wouldn’t like to be published online. On the other hand, Salvatore equally cannot promote himself on Facebook with a nice photo or accomplishment without his friends mocking him for taking himself too seriously.

Salvatore works as an IT consultant for a medium-sized company in Lecce and is renown as a quiet and refined person. In this context, both situations described above would challenge the image people in his hometown have constructed of him. In contrast, he feels that in Lecce he can be a ‘different person’ (un’altra persona) as people there actually encourage this kind of diversity. He commutes to work everyday and sometimes spends whole weekends in the city staying with friends. However, Salvatore is more interested in taking care that Facebook corresponds to the image he has in his hometown, rather than the one he constructs in the city.

What this story points to is how most people in southeast Italy use public-facing social media so that it reflects the relationships and image they have in their home communities. The problem, then, is that this image may vary significantly with social behavior between rural places, small and medium-sized towns and metropolitan places. Writing on these kinds of differences at the turn of the 20th century, sociologist Georg Simmel shows why that what varies essentially is the balance between ‘the objective spirit’ and ‘the subjective spirit.’ That is, in metropolitan places people have to cope with an avalanche of essentially objective issues, from money economy and commerce to mass-produced commodities, which places emphasis on individuality and rationality. In contrast, people living in rural areas, with the slower more habitual, and fewer flows of life, are closer to the ‘spirit’ (or Geist) of people and objects, and, among other things, this allows for more space for subjectivity in social relations.

My ethnographic material cannot really engage with this theoretical proposition as my research was done in a small place. However, what I can agree with is that people in Grano build relationships based on traditions and institutions which incorporate time, a certain predictability and more opportunities to share this ‘spirit’ that are simply unavailable in bigger places. In this context, most people in Grano sense that social media should reflect these very specific local values exactly because they are quintessentially subjective and thus recognizable, before any global forms and tastes.

Aspiring Politician? Try Facebook to build your personal brand.

By Shriram Venkatraman, on 8 September 2015

Personal brand building through social media requires a strategically planned presentation of oneself to a general audience. This is by no means new within Indian politics. Consider the way Mahatma Gandhi first wore suits, and then other forms of dress before ending up with the well known hand-spun garments of an ascetic. In contemporary India, Twitter seems to be the most popular choice of medium for such an exercise, as exemplified by the current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, who is active both on Twitter and Weibo and is even hailed as an Indian social media superstar with 14.8 Million followers on Twitter. However, in my own fieldsite at Panchagrami, the aspiring Politicians who are likely to be school dropouts find that Twitter requires a level of English that is intimidating. For them, the architecture of Facebook offers more possibilities, and the greater importance of visuals makes this a more appropriate tool for them and their followers.

Saravanan, aged 28 years, is an eighth grade school dropout and now works as a water supplier for a local village governing council (called ‘Panchayat’ in India). He also assists the president of this council in matters relating to the area. Saravanan, is an active member of the current major opposition party in Tamil Nadu and an arch rival of the ruling state party to which the Panchayat president belongs, though, personally they get on well with each other.

Wanting to establish himself as a politician, he had little by way of funds, but realised that the current local politicians had failed to forge links with the new middle class migrants to the area. He recognised that social media would be the best tool to help bridge this gap. Further, it would also help link with the increasing numbers of locals from the lower middle classes who were using Facebook.

What stands out in his profile is that it is very visually oriented and has very little text. He posts pictures that show him as a person who is always working for other people and demonstrating his devotion to public service. He always wears a white shirt with a black pant, an accepted professional dress code for politicians, he regularly posts pictures of himself in party meetings with atleast 500 to 600 members in attendance and some of the the well-known party high command in view.

Saravanan is pretty active in friending young people and the new middle class using Facebook to develop his social circle. A final advantage of this strategy is that by working through these visual associations and not overtly projecting himself he is less likely to antagonize the present members of the board. For him the effective use of social media is to use visual means to create and cultivate his image as that of “a common man” always in the service of people.

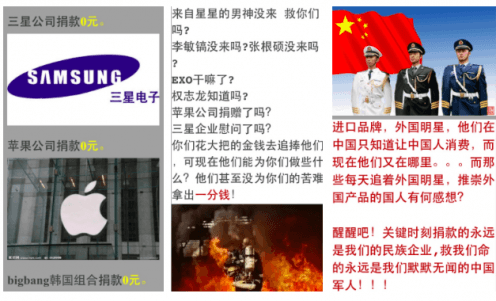

What ordinary Chinese people post on social media after the Tianjin Blast

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 24 August 2015

“For two days, my WeChat news feeds has been awash with all kinds of articles and images about the Tianjin blast. But after merely two days, the routine on social media came back, food photos, holiday photos, kids photos, articles teaching you how to deal with the relationship between you and your mother-in-law all came back. People seemed to forget about the disaster already.”

A week after the appalling blast in Tianjin, China on 12th August, Zhou, a free-lance journalist and photographer, who I got to know when I was doing field work in Southeast China last year, told me her feelings concerning Chinese social media reaction to this event. She could not hide her disappointment.

Zhou’s remark accords with my own observations of my informants’ posts on both QQ and WeChat, the two Chinese dominant social media platforms. And like Zhou, I heard the news for first time from my personal WeChat. Social media has become the main (if not the first) channel for access to various kinds of information. But unlike traditional channels, social media presents these different kinds of information from news to a whole range of personal conversation together without curation. This clearly contributes to Zhou’s feelings about information fragmentation on social media where significant news becomes diluted by the huge amount of the ‘daily life’ content on social media.

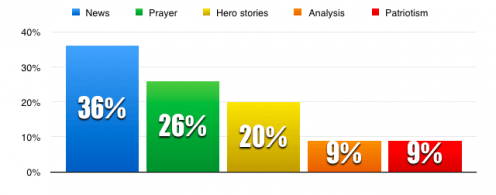

But what exactly ordinary Chinese people post on their personal social media profiles vis-a-vis the blast? After the completion of 15 months fieldwork, I continued to follow two groups on social media on a daily basis. One comprise the rural migrants in a factory town where I did most of my field work (50 persons), and the other one a control group with whom I conducted in-depth interviews in Shanghai (30 persons). The table below shows how remarkably different the Tianjin blast related social media performance are of these two groups of people (All the people in Shanghai use WeChat, and the majority of rural migrants remain with QQ). Taking the four days following the blast (from 13 August to 17th August), on all 80 social media profiles, 44% of postings (42 postings out of 95) were related to the blast, of which almost 53% were posted the day after the blast. In general, there are five themes: News about the blast (36%), Prayers for Tianjin (26%), Hero stories (20%), in-depth analysis (9%), and patriotism postings (9%).

The News postings were straightforward, usually news reports with photos and very simply comments by people who shared it, such as “It’s shocking!”, “How terrible!” or “I am so sorry for Tianjin”. 60% of those news-based stories shared on social media came from people in Shanghai.

The ‘Prayers for Tianjin’ postings are those memes with text like ‘pray for Tianjin’ (see screenshots below). Some postings shared on people’s profiles went even moralized by claiming “Tonight we are all from Tianjin and suffer the same suffering, if you are Chinese please share this!”, a bit like “We are Charlie”. The majority (64%) of those memes come from rural migrants.

The ‘hero stories’ are also widely shared on people’s social media profiles where both people from Shanghai (50%) and rural migrants (50%) seems to show similar interests in stories like how firemen sacrificed their own lives, running into the fire when everybody was fleeting away; or how sniffer dogs worked day and night in order to save human beings.

In-depth analysis refers to editorials focusing on the cause of the accident. Articles of this kind were only shared only by people from Shanghai, who had education at master-level and above. In one of the articles the government and disaster relief system is strongly challenged. There is explicit criticism of the way that after a disaster people only share ‘pray for ***’ memes on social media, rather than really asking for the truth behind the disaster.

In contrast to the situation of ‘in-depth analysis’, rural migrants contributed all the ‘patriotism’ postings. One typical ‘patriotism’ (see screenshots below) started with a list of Chinese celebrities and companies who had donated money for the disaster relief, followed by the list of foreign celebrities and companies (such as south Korean stars, Samsung and Apple) who didn’t donate any money for this Tianjin blast. In the end of the article, it was urged that Chinese people should love the state since only the Chinese army can protect them and people who are big fans of foreign stars and foreign products should feel ashamed of themselves. Though I happen to know that one such person, a factory worker, had just spent on whole month salary on a iPhone prior to a blind date with a girl arranged by one of his fellow villages,

A close inspection of this pattern of posting on social media is revealing then not just about reactions to a disaster, but also key issues in contemporary China, such as the differences created by education and the appeal of nationalist ideology.

Ropa americana online: the local market for used clothing

By ucsanha, on 15 August 2015

A Facebook announcement from an online shop in northern Chile announces “Jackets, Vests, and Sweatshirts”

Ebay, Etsy, Alibaba, and Taobao have changed the way many people around the world shop. Now, you can get virtually any product from anywhere, delivered right to your door. Tom McDonald has even observed companies that have sprung up to make this possible in rural China where even courier services does not deliver (also see his blog about business Facebook pages). But in northern Chile, people aren’t really all that concerned with getting interesting things from far off places. To them, ropa americana [American clothing, code for used goods] is the cheapest and least impressive form of dressing. If one is looking for style, the department stores in the larger cities will do just fine.

But this doesn’t mean that there’s no market for these goods online. Many people, particularly older women, have developed “shops” through Facebook in order to sell used clothing. Just like their counterparts who operate physical used clothing shops in the semi-formal markets around the city, these women buy used clothes in bulk, and sell it to individual consumers. But instead of renting a stall, they take pictures of the individual items to upload to Facebook accounts that they have just for that purpose. When a potential buyer likes and item, they will negotiate a price (usually about $4 for a tshirt, a bit more for jeans or a dress, up to $20 for a coat), and a time and place to meet for the exchange. While new customers may simply ask the price as a comment on the picture, or send a private message through Facebook to arrange a drop-off, regular customers will send WhatsApp messages asking about specific items, hoping to get the best of the best before they even make it to the Facebook page.

Paola, who sells clothes mostly for men told me that a miner requested she meet him as he got off the bus, coming home from his shift at the mine. He had ripped his coat while at work, and was afraid of being very cold between the bus drop off and walking a few blocks home. Paola agreed to meet him at midnight at the bus, for just a few extra dollars.

So while in many ways social media has the ability to expand consumption options globally and allow people access to cosmopolitan goods they might not have imagined a decade ago, it can also take on a form that is distinctly local and personal. Like Paola meeting the miner at his bus, this is just one way that social media can truly strengthen the community bonds that people feel in their local place.

Sharing anthropological discoveries on social media: ‘marketing’ or ‘interactive learning’?

By Daniel Miller, on 6 August 2015

Social media and engaging anthropology? (Photo: Pabak Sarkar CC BY 2.0)

Over the last year, people have often asked us questions like “Surely you will market your project using social media?” or, “What exciting campaigns based on social media will make your project a success?”

Well the answer is that indeed we think we have learnt a good deal about social media. What it is useful for, but equally where claims are made that are not borne out by our evidence. We have concluded that this huge emphasis on marketing through social media has far more to do with the wishes and desires of the marketing industry for this to be the case than any sober assessment of what social media actually is.

Looking at our research as a whole, we find quite limited successful employment of social media as a form of mass marketing and promotion. Yes certainly in some cases, but in most of our field sites it’s force is quite limited.

Our primary theorisation of social media is instead as a form of sociality and the formation of small groups for internal discussion. It is not generally a means for trying to reach new or different people but rather for consolidating social groups that are largely known. Some platforms such as LinkedIn and Twitter clearly command a wider presence but even here, social media generally works best for groups that are linked by common interests such as devotees of Star Wars, rather than in reaching a generic audiences.

We are not alone in this. Fore example, even people in business are starting to appreciate that Twitter is not always effective in driving traffic in the direction that they would wish.

So yes, we do envisage a role for social media in the dissemination of our project findings but mainly other than as a tool for mass marketing. We see social media as an important instrument for interactive learning. So people who take our online course will be encouraged to form small groups in which they can discuss the material and make and receive comments about what they are learning.

People who cannot meet physically in class rooms can use social media for discussion. Social media can also harness one’s personal networks to disseminate information in limited ways, and much of the more successful commercial usage we observe in our field sites relates to businesses where personal interaction is also important.

What people seem to imagine is that a project that studies social media will – for that very reason – concentrate on using social media. But we have never been advocates for social media.

The point of our research is to remain open and cautious about our findings, and we are just as comfortable noting the limitations and negative effects of social media as its potentials.

Close

Close