Visualising Facebook by Daniel Miller and Jolynna Sinanan

By Daniel Miller, on 7 March 2017

Today marks the publication of a new book called Visualising Facebook, which I have written with Dr Jolynna Sinanan. It is available as a free download from UCL Press and also for purchase in physical form. One of the key arguments from the larger Why We Post project, of which this book is one out of eleven volumes, is that human communication has fundamentally changed. Where previously it consisted almost entirely of either oral or textual forms, today, thanks to social media, it is equally visual. Think literally of Snapchat. So, it is a pity that when you look at the journals and most of the books about social media, they often contain either no, or precious few, actual visual illustrations from social media itself. One of the joys of digital publication is that it is possible to reproduce hundreds of images. So, our book is stuffed to the gills with photographs and memes taken directly from Facebook, which is, after all, our evidence.

For example, as academics, we might suggest that the way women respond to becoming new mothers in Trinidad, is entirely different from what you would find in England. In the book, we can reproduce examples from hundreds of cases, where it is apparent that when an English woman becomes a mother she, in effect, replaces herself on Facebook with images of her new infant. Indeed, these often become her own profile picture for quite some time. By contrast, one can see postings by new mothers in Trinidad, where they are clearly trying to show that they still look young and sexy or glamorous, precisely because they do not want people to feel that these attributes have been lost, merely because they are now new mothers.

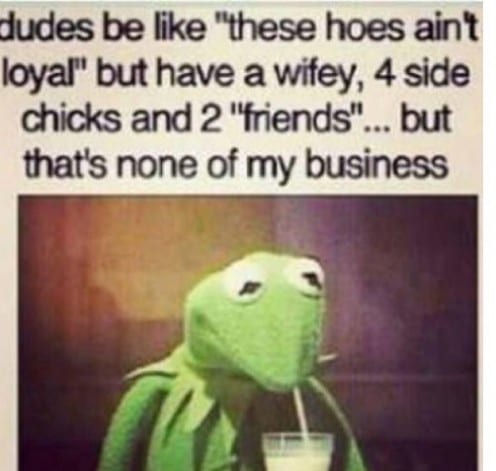

In writing this book we examined over 20,000 images. These provide the evidence for many generalisations, such as that Trinidadians seem to care a good deal about what they are wearing when they post images of themselves on Facebook. While, by and large, English people do not. But this becomes much clearer when you can see the actual images themselves. Or we might suggest that English people are given to self-deprecating humour, while Trinidadians are not. Or that in England gender may create a highly repetitive association between males and generic beer, as against women with generic wine. In every case, you can now see exactly what we mean. We also have a long discussion about the importance of memes and why we call them `the moral police of the Internet’. How memes help to establish what people regard as good and bad values. This makes much more sense when you are examining typical memes with that question in your head.

To conclude, given the sheer proportion of social media posting that now consists of visual images, it would seem a real pity to look this gift horse in the mouth. Firstly, it has now become really quite simple to look at tens of thousands of such images in order to come to scholarly conclusions. But equally, it is now much easier to also include hundreds of such images in your publications to help readers have a much better sense of what exactly those conclusions mean and whether they agree with them.

This post was originally published on the #NSMNSS blog here.

Close

Close

In The Glades it is very common for people to imply that organisations such as the church represent genuine communities which are now being undermined and replaced by social media such as Facebook which instead represent a kind of community-lite. But these same villagers produce evidence which is entirely contrary to this claim. As one parishioner noted `The church put on a Facebook page, a lot of people then did become friends with the church. Then I realised how many people are actually on there that I know and I see every Sunday. (Have you got to know them better now through Facebook?) Yeah. A lot better. Normally, you don’t really discuss what jobs they do or what social activities they do. You meet them in a church setting, talk about church related things.’ She then notes that thanks to Facebook she has come to realise who is related to who and who she knew about through other channels Another villager noted `When my husband had his heart attack last year I put on that he’d had a heart attack, it was amazing how many people sort of commented on it, wanted to know how he was, when he had his heart operation, quite a few of them were praying for him, that sort of thing. That’s nice cos I thought I’ve only ever known you through Farmville, interested enough to comment and think about it. A lot of the people I know are Christian people.’

In The Glades it is very common for people to imply that organisations such as the church represent genuine communities which are now being undermined and replaced by social media such as Facebook which instead represent a kind of community-lite. But these same villagers produce evidence which is entirely contrary to this claim. As one parishioner noted `The church put on a Facebook page, a lot of people then did become friends with the church. Then I realised how many people are actually on there that I know and I see every Sunday. (Have you got to know them better now through Facebook?) Yeah. A lot better. Normally, you don’t really discuss what jobs they do or what social activities they do. You meet them in a church setting, talk about church related things.’ She then notes that thanks to Facebook she has come to realise who is related to who and who she knew about through other channels Another villager noted `When my husband had his heart attack last year I put on that he’d had a heart attack, it was amazing how many people sort of commented on it, wanted to know how he was, when he had his heart operation, quite a few of them were praying for him, that sort of thing. That’s nice cos I thought I’ve only ever known you through Farmville, interested enough to comment and think about it. A lot of the people I know are Christian people.’