Biological Traits Influence Vulnerability to Climate Change in Birds, Amphibians and Corals

By Claire Asher, on 25 June 2013

Climate change is fast becoming a reality, and with temperature rises of between 0.8°C and 2.6°C predicted over the next 35 years, biodiversity will certainly be impacted, with many species set to suffer declines or potential extinction. But all species are not equal and certain traits may make species more or less vulnerable to climate change than others. A new model presented in PLOS one this month investigates the impact of biological traits, such as physiology, ecology and evolutionary history, on vulnerability to climate change for some of the most threatened groups: birds, amphibians and corals. Around 10% of species are both highly vulnerable to climate change, and already listed as threatened with extinction. The model also identifies potentially vulnerable species for future conservation priorities, giving biologists a head-start in trying to slow the inevitable loss of biodiversity that climate change will bring.

Many researchers are interested in predicting how biodiversity might respond to climate change. Biodiversity is essential to human survival – diverse, functional ecosystems provide us with food, water and medicine. However, predicting how ecosystems might respond to changes in temperature and rainfall is a complicated matter. Most previous models have considered the availability of suitable habitat for species based upon their current range and predictions of temperature changes. However, not all species are created equal – biological traits of individual species are likely to play an important role in determining species survival. For example, some species are adapted to a very specialised habitat or are poor as dispersal and so may struggle to find alternative habitats even if they are available. Other species have long generation times and produce few young, or have very limited genetic diversity in the population, making adaptation to new habitats more difficult. Species like these are likely to be more vulnerable to climate change than generalists who are good at dispersal and produce lots of offspring. Not considering the biology of a species when modelling responses to climate change can lead to under- or over-estimations of how vulnerable a species actually is.

Accounting for Biology

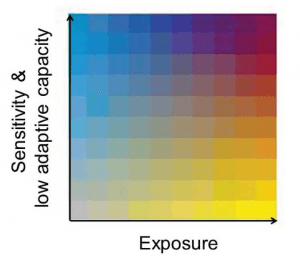

To address this issue, Foden and colleagues, working in collaboration with Professor Georgina Mace from CBER, developed a systematic framework for assessing species vulnerability to climate change, and applied this model to three of the best-studied, and most endangered groups of animals: birds, amphibians and corals. They considered three factors – sensitivity (whether a species can survive where it is), exposure (the predicted extent of change under climate models), and adaptive capacity (whether a species can avoid the negative impacts of climate change by moving or evolving).

In consultation with extinction risk specialists, they identified 90 biological, ecological, phsyiolocial and environmental traits which are likely to influence vulnerability to climate change. In particular, they identified habitat specialisation, rarity, environmental tolerance, disruption of environmental triggers and interactions with other species as key components of species sensitivity to climate change. Adaptive capacity is composed of dispersal ability, barriers to dispersal, genetic diversity, generation length and reproductive output. They assessed these traits for each of 16,857 species of bird, amphibian and coral, across the globe.

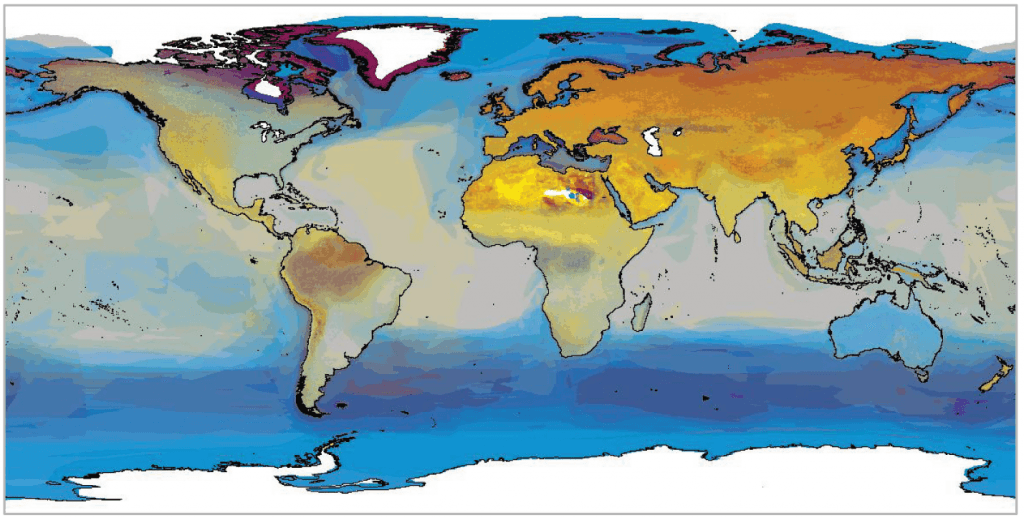

The proportion of species in a region that are sensitive or have limited adaptive capacity (blue), high exposure to climate change (yellow) or both (maroon).

Armed with these traits, they were able to determine sensitivity, adaptive capacity and exposure for each species, and generated maps of where species may be particularly vulnerable. They found that around 24% – 50% of bird species, 22% – 44% of amphibians and 15% – 32% of corals are both sensitive and exposed, and have limited capacity to adapt. They identified the Amazon region as containing many highly vulnerable birds and amphibians. Many bird species were also highly vulnerable in central Eurasia, the Congo basin, the Himalayas, Malaysia and Indonesia, with amphibians most vulnerable in north Africa, eastern Russia, and the northern Andes. The waters around Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines were hot-spots for highly vulnerable corals.

A Silver Lining

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. The study also identified some species and regions where species’ traits may make them more able to cope with climate change. Around 28% -53% of bird species, 23% – 59% of amphibians and 30% – 55% of corals may survive projected climate changes because of their inherent ability to disperse or adapt to change. In particular, southern Asia and North America may see less severe biodiversity declines than previously thought.

The interplay between climate change and biodiversity is complex, and unlikely to be uniform across taxonomic groups. It is important to consider the physiological, ecological and evolutionary traits of individual species when making predictions about the impact of climate change. This study considered the effects of temperature and rainfall changes, as well as ocean acidification and sea-level rise, on global biodiversity. However, many other factors will influence whether species survive over the long-term – habitat destruction, invasive species and pollution are also major drivers of extinction which need to be taken into account when predicting the future of a species. Taking into account the biology of a species, and it’s interaction with other species, is a major step forward in our understanding of how biodiversity will respond to the impending climate changes that are now inevitable.

Original Article:

This research was made possible by funding from the MacArthur Foundation.

Close

Close