Abstract

Compassion can be defined as “a sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it”(Gilbert, 2017). Compassionate pedagogy could be viewed as a response to a growing sense of zombification of the academy. A universal design for education approach to learning design and resource selection, informed in part by learning analytics, could be considered as components of a compassionate pedagogy. However, as compassion requires an innate motivation, it is this motivation rather than a formal framework or policy requirement that makes these activities the actions of a compassionate pedagogue.

Introduction

The development of massified Higher Education and growing concerns around the increasing use of data in both the ranking and management of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) has led to a growing body of scholarly work around the notion of the Zombie Academy (Brabazon, 2016)(Moore, Walker, & Whelan, 2013). Neo-liberal discourse and approaches to governance and accountability are increasingly commoditizing education and reducing the role of the student to consumers whilst simultaneously stripping the function and roles of our HEIs of their social, cultural and political meanings (Moore et al., 2013).

Simultaneously, there is a growing rise in literature around and a move towards compassionate pedagogy. Compassion can be defined as “a sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it”(Gilbert, 2017). Teachers are said to show compassion towards students if they endeavour to see things from the students’ perspective (Waghid, 2014), however this omits the need for motivation to act in a way that is of benefit for students. This is encapsulated in (Hao, 2011)’s definition of Critical Compassionate Pedagogy: “a pedagogical commitment that allows educators to criticize institutional and classroom practices that ideologically underserve students at disadvantaged positions, while at the same time be self-reflexive of their actions through compassion as a daily commitment”.

Being a compassion pedagogue and developing compassionate pedagogy can therefore be said to be about the day-to-day choices made by educators. These choices will include decisions about learning design, selection of learning materials and the use of data to inform learning design and student feedback.

Compassionate Pedagogy in Practice

The increase in the proportion of young adults attending Higher Education Institutions has led to an increasingly diverse student intake (‘Who’s studying in HE?: Personal characteristics | HESA’, n.d.), however this is not always represented in the curricula or in how the curricula are presented to students.

In recent years there has been growing dissatisfaction with what some students describe as ‘pale, male and stale’ curricula. This has resulted in some high profile student campaigns to decolonise the curriculum at a number of leading UK universities including UCL (‘Why is My Curriculum White?’, n.d.) and Cambridge University (https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/oct/25/cambridge-academics-seek-to-decolonise-english-syllabus), becoming a point of discussion and debate across the sector.

Selecting learning resources and situating learning in a manner that reflects the differing voices, perspectives and experiences of those generating and consuming knowledge are a fundamental part of compassionate pedagogy.

Even if our curricula are representative, how do we ensure an equity of experience for our students? Ableism in academia is endemic and so the concern for equality and equitability is on the increase (Brown & Leigh, 2018). In 2016/17 12% of students were known to have a disability, many of whom may not have a visible disability (‘Who’s studying in HE?: Personal characteristics | HESA’, n.d.). Therefore, learning design and design choices made when creating learning resources are also key components of an inclusive, compassionate learning environment. Examples of these choices may include automatically adding closed captions to all videos created by an instructor, avoiding the use of colour to infer meaning, ensuring resources are created in formats that are compatible with institutionally supported accessibility tools or selecting an open textbook as the main course text.

These can both be considered as examples of universal design in education (UDE), where UDE is defined as “the design of educational products and environments to be useable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialised design” (Burgstahler, 2015). This requires the acknowledgement and consideration of the diverse characteristics of all eligible students, these may include ability, language, race, ethnicity, culture, gender, sexual orientation and age. Therefore, the application of universal design principles can be considered an act of compassion.

For a course at a HEI, the products and environment would include the curriculum, facilities and technology used in the course. At a macro level this may be choosing teaching strategies, and at the micro, facilitating small group discussions. For example, when using a learning method such as UCL’s ABC method, the products and environments will include considering the variety of learning types selected, the blend of online and offline activity and the assessment load, both formative and summative. The Learning Designer tool enables you to see how much time is spent on tasks and what percentage of directed time is spent on each learning type (‘Learning Designer’, n.d.). Additionally, tools such as the Exclusion Calculator created by the University of Cambridge enables the quantification of accessibility of resources and helps to prioritise improvements.

The role of data

Learning analytics is an ongoing trend and has been identified as one of the ‘Important Developments in Technology for Higher Education’ for 2018/19 (Becker et al., n.d.). Learning analytics has been defined as ‘the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for purposes of understanding and optimising learning and the environments in which it occurs’(Siemens & Gasevic, 2012).

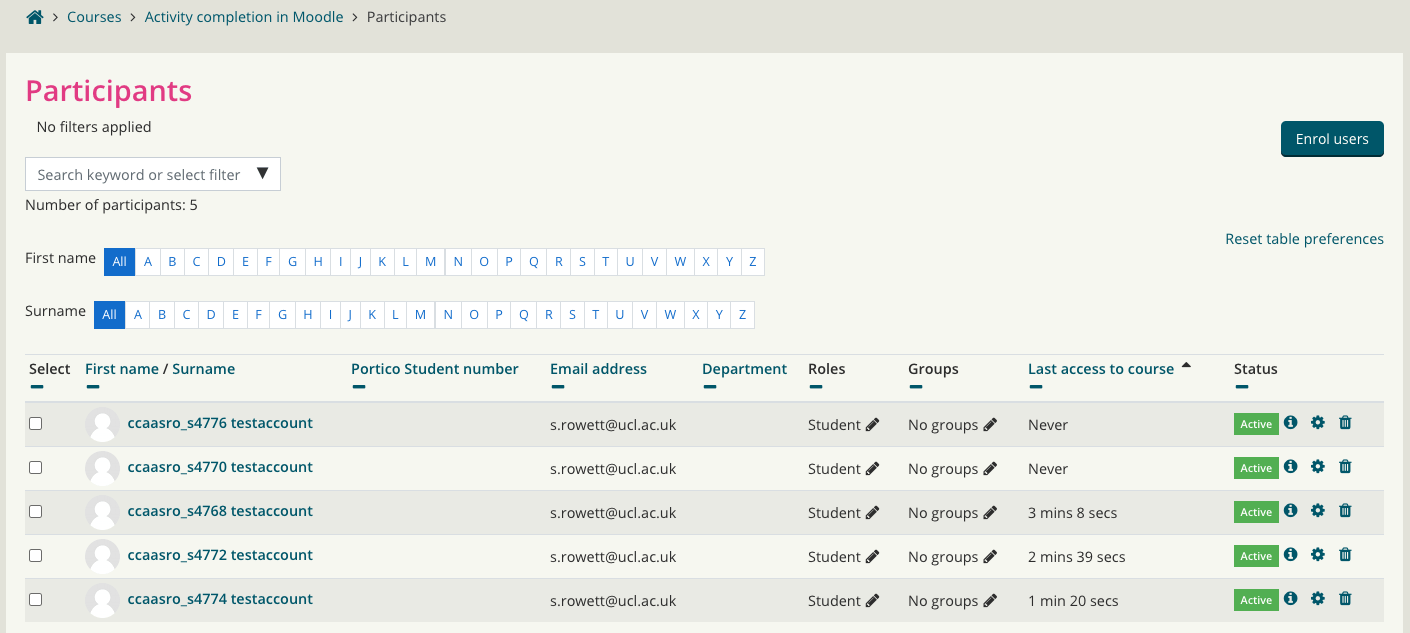

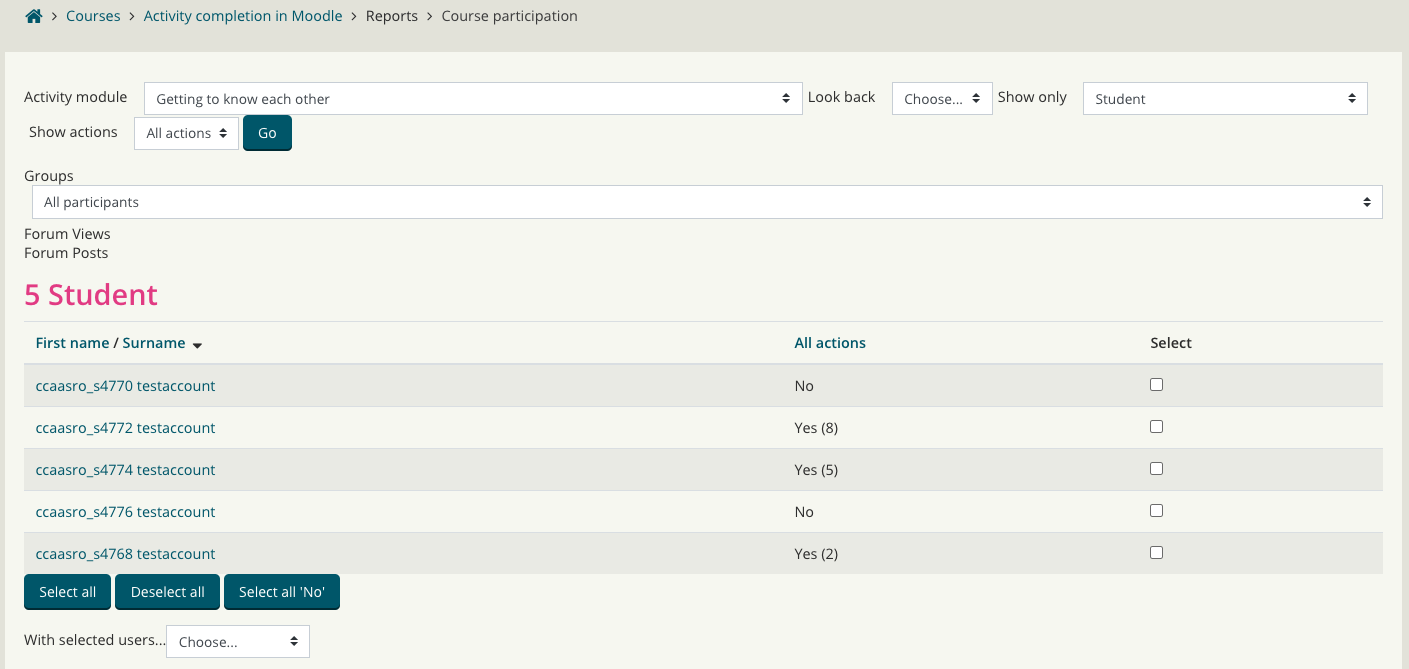

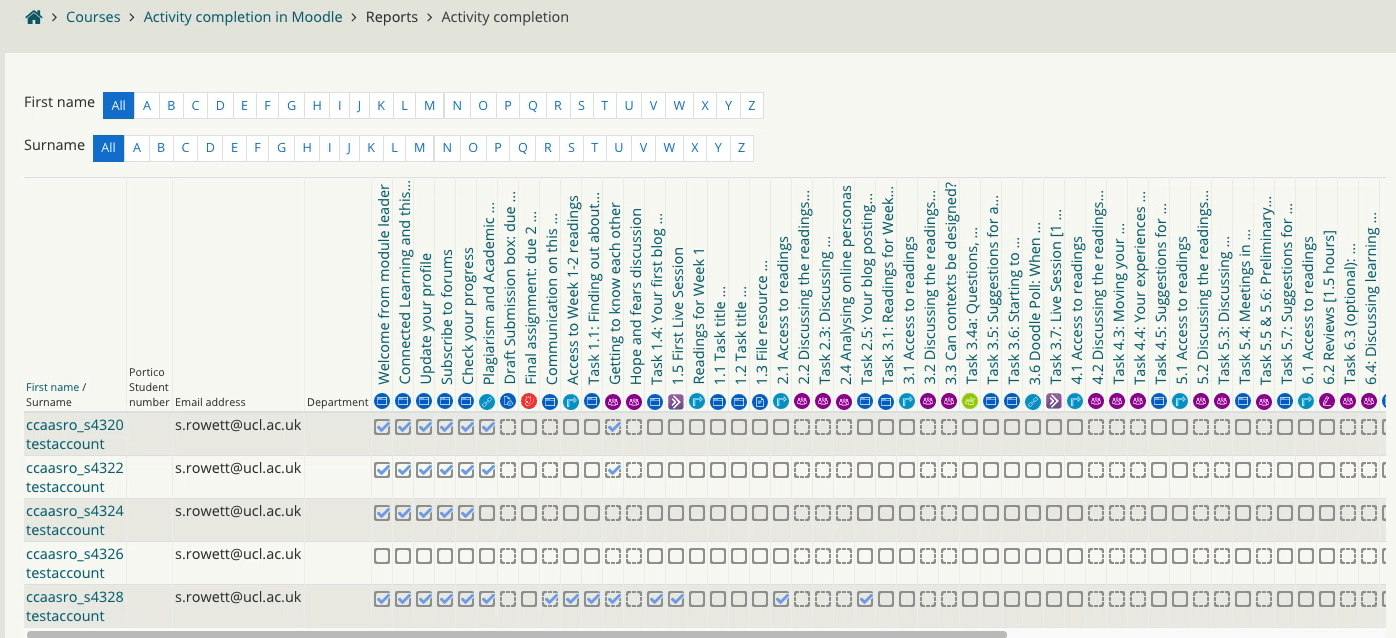

Higher Education Institutions store and generate a plethora of data about students and their interactions with the institution’s IT services and systems. Some of this data can be leveraged by educators to inform their practice and tailor student support. For example, the Echo 360 Active Learning Platform system enables students viewing recordings to flag content that they find confusing. This data could then be used by the instructor to inform planning for forthcoming lectures or tutorials. Demographic data could be used to identify students who may need additional support as they may have a specific learning difficulty or be first in family to attend university. It is also possible to identify students who may be over-using resources in an institution’s Virtual Learning Environment, e.g. repeatedly completing the same formative quiz, that may indicate support is required.

This data can be collated for different purposes; automated actions (e.g. email triggers) or as data for humans (e.g. tutors or students themselves) to interpret. An example of automated actions is Newcastle University’s Postgraduate Research Student attendance monitoring process undertaken by the Research Student Support Team (RSST) and the Medical Sciences Graduate School (MSGS). Of the three emails that can be sent to a student, the Level 1 email is an informal automated reminder sent to a student if there has been no recorded and confirmed meetings within 6 weeks (‘Attendance Monitoring’, n.d.).

However, this does not mean that actionable insights will necessarily be drawn or that action will take place. Motivation is required at institutional and practitioner level to make meaningful use of the data, returning us back to our notion of compassionate pedagogy and a motivation to criticize institutional and classroom practices for the benefit of students. An added complication are concerns around HEIs’ obligation to act on any data analyses, in particular providing adequate resources to ensure appropriate and effective interventions (Prinsloo & Slade, 2017).

Conclusion

In this paper we have discussed how accessible learning design and moves to liberate curricula can be perceived as acts of compassion, however these may be undertaken by non-compassionate pedagogues in response to mandated requirements from institutional management, for example UCL’s Inclusive Curriculum Health Check (UCL, 2018), potentially becoming another part of the zombie academy.

Likewise, we have identified that learning analytics can have a role to play. However, it too needs appropriately motivated institutions and staff to utilise this technology in a compassionate manner.

The key notion that separates compassion from empathy or sympathy is the desire to help, or in some definitions motivation to act. It is this combination of awareness of others and motivation to act in a meaningful way, that determines whether a pedagogue is compassionate or not. These are not things that can be embedded in a formal framework or policy document, but are a culture and mindset that need to be cultivated.

References

Attendance Monitoring. (n.d.). Retrieved 18 September 2018, from https://www.ncl.ac.uk/students/progress/student-resources/PGR/keyactivities/AttendanceMonitoring.htm

Becker, S. A., Brown, M., Dahlstrom, E., Davis, A., DePaul, K., Diaz, V., & Pomerantz, J. (n.d.). Horizon Report: 2018 Higher Education Edition, 60.

Brabazon, T. (2016). Don’t Fear the Reaper? The Zombie University and Eating Braaaains. KOME, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.17646/KOME.2016.21

Brown, N., & Leigh, J. (2018). Ableism in academia: where are the disabled and ill academics? Disability & Society, 33(6), 985–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1455627

Burgstahler, S. (2015). Universal design in higher education : from principles to practice / edited by Sheryl E. Burgstahler (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard Education Press.

Gilbert, P. (Ed.). (2017). Compassion: Concepts, Research and Applications (1 edition). London ; New York: Routledge.

Hao, R. N. (2011). Critical compassionate pedagogy and the teacher’s role in first‐generation student success. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2011(127), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.460

Learning Designer. (n.d.). Retrieved 17 September 2018, from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/learning-designer/index.php

Moore, C., editor of compilation, Walker, R., editor of compilation, & Whelan, A., editor of compilation. (2013). Zombies in the academy : living death in higher education / [edited by] Andrew Whelan, Ruth Walker and Christopher Moore. Bristol : Intellect.

Prinsloo, P., & Slade, S. (2017). An elephant in the learning analytics room: the obligation to act (pp. 46–55). ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/3027385.3027406

Siemens, G., & Gasevic, D. (2012). Guest editorial-Learning and knowledge analytics. Educational Technology & Society, 15(3), 1–2.

UCL. (2018, May 11). New checklist helps staff rate inclusivity of their programmes. Retrieved 17 September 2018, from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/teaching-learning/news/2018/may/new-checklist-helps-staff-rate-inclusivity-their-programmes

Waghid, Y. (2014). Pedagogy Out of Bounds: Untamed Variations of Democratic Education. Sense Publishers. Retrieved from //www.springer.com/la/book/9789462096165

Who’s studying in HE?: Personal characteristics | HESA. (n.d.). Retrieved 9 September 2018, from https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/whos-in-he/characteristics

Why is My Curriculum White? – Decolonising the Academy @ NUS connect. (n.d.). Retrieved 10 September 2018, from https://www.nusconnect.org.uk/articles/why-is-my-curriculum-white-decolonising-the-academy

Close

Close