By Jake Anders

Covid-19 caused significant and widespread disruption to young people’s education. But the effects were not the same for everyone. Many pre-existing inequalities have been exacerbated, including those between state schools and independent schools.

The pandemic has had a major effect on the education and wider lives of children and young people, ranging from access to early years provision, learning losses among school age pupils, and broader effects on mental health and wellbeing (Farmer, 2020). But the impact has not been the same for everyone.

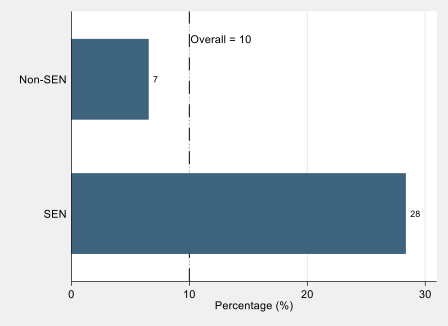

It has become clear that school closures and online learning due to the pandemic have exacerbated existing inequalities in education. Those from disadvantaged backgrounds and pupils with additional needs (including special educational needs and disabilities) have been especially badly affected by the disruption. In this article, we focus particularly on inequalities that emerged through differences in the responses of state and private schools.

Less than 10% of young people in England attend a private school during their education. Nevertheless, these institutions have an outsized influence on the persistence of educational advantage. They are highly socially selective, with the vast majority of those attending private schools coming from families in the top 10% of the income distribution (Anders et al., 2020; Henseke et al., 2021).

Further, the gap in resources between state and private schools is large (Green et al, 2017). It has grown larger over the past decade: from £3,100 per pupil per year in 2010/11 to £6,500 by 2020/21 (Sibieta, 2021).

Based on a combination of these factors, people who have attended private schools are disproportionately likely to be employed in high-status jobs later in life (Sullivan et al., 2016). Privately educated graduates are a third more likely to enter a high-status occupation than state-educated peers from similar families and neighbourhoods (Macmillan et al., 2015).

Early on in the pandemic, there were many anecdotes about differences in school responses, emphasising some schools’ rapid move to live online lessons. But much of the data available to test these narratives only covered state schools (a notable exception is Andrew et al., 2020).

Things have changed with new data from the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities study (COSMO). This cohort study of young people in Year 10 at the pandemic’s onset provides high quality new data to explore the issue. Here, we consider some of the differences that emerged between state and private schools due to the large resource differences and why they matter.

Schooling in lockdown

When the first national lockdown began in the spring of 2020, schools played a vital role in responding to myriad challenges facing their pupils. With concerns about welfare and wellbeing, it was understandable that tasks such as free school meal voucher distribution, checking on how pupils’ families were coping in terms of mental health, welfare and food, and providing information on where they could obtain support distracted from efforts to organise online learning for pupils. This was particularly acute for schools with many pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds (Moss et al., 2020).

With more resources and fewer issues to solve, private schools were able to move quickly to set up alternatives to in-person classes. For example, 94% of private school participants who responded to the COSMO study received live online lessons during the first national lockdown.

This was 30 percentage points higher than the rate reported among those in comprehensive schools. The vast majority (84%) also reported receiving more than three online classes per school day during this period, compared with 41% in state grammar schools and 33% in state comprehensive schools.

Figure 1: Provision of live online lessons, by school characteristics, lockdown one (March-June 2020) and lockdown three (January-March 2021)

Source: COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities study (COSMO).

Notes: N=12,505, including 11,317 in state comprehensive group; analysis weighted to account for study design and young person non-response.

There were not national school closures during the second lockdown (in the autumn of 2020). By the third national lockdown in early 2021, state schools with the most advantaged intakes had largely caught up with private schools’ remote learning provision.

Pupils in these schools were now similarly likely to be offered remote lessons (around 95% in state grammar and state comprehensive schools with the least disadvantaged intakes). But they were still not providing as many per day, with 82% of those in state grammars and 71% in the least deprived state comprehensives reporting receiving more than three online classes per day, compared with 93% in private schools.

On the other hand, state schools with more disadvantaged intakes had made less progress on both fronts – 80% of pupils in these schools reported receiving any online lessons and 53% more than three per day – remaining behind in terms of online lesson provision.

Pupils at independent schools were also more likely to have regular contact with a teacher outside class during lockdowns. Here, state schools caught up slightly in the third lockdown.

But state comprehensive pupils were more than twice as likely to report difficulties in accessing support from teachers than pupils at private schools (17% compared with 8% in the third lockdown).

Pupils at private schools also reported spending more time on schoolwork during lockdowns than their state school peers. This added up to more than one extra working day per week of time spent on schoolwork in both the first and third lockdowns.

Many of these differences are not down to the schools directly. Rather, they are due to challenges faced depending on pupils’ circumstances.

For example, almost a quarter of pupils attending state comprehensives with the most deprived intakes did not have access to a suitable device for joining remote classes in the first lockdown. This figure was under 2% for pupils at independent schools.

Similarly, 13% of those at state comprehensive schools reported issues due to having to share devices needed to take part in online learning. Only 4% at independent schools faced the same issue.

Catch up

Given these inequalities, it is unsurprising that young people at state schools were more likely to think that their progress has suffered because of the Covid-19 disruption. In state schools, 81% of pupils reported this, compared with 72% at private schools. To address this, a much larger effort to support young people in state schools to catch up is needed.

This is especially important as the gap in disruption to learning did not stop with the resumption of in-person schooling. For example, teacher absence has taken a larger toll on state schools in the post-restrictions period of the pandemic.

Staff absence rates due to Covid-19 infections in state schools have been higher than private schools. In a snapshot survey in early 2022, 20% of state school teachers reported that at least one in ten staff in their school were absent. Only 12% of private school staff reported the same (Sutton Trust, 2022).

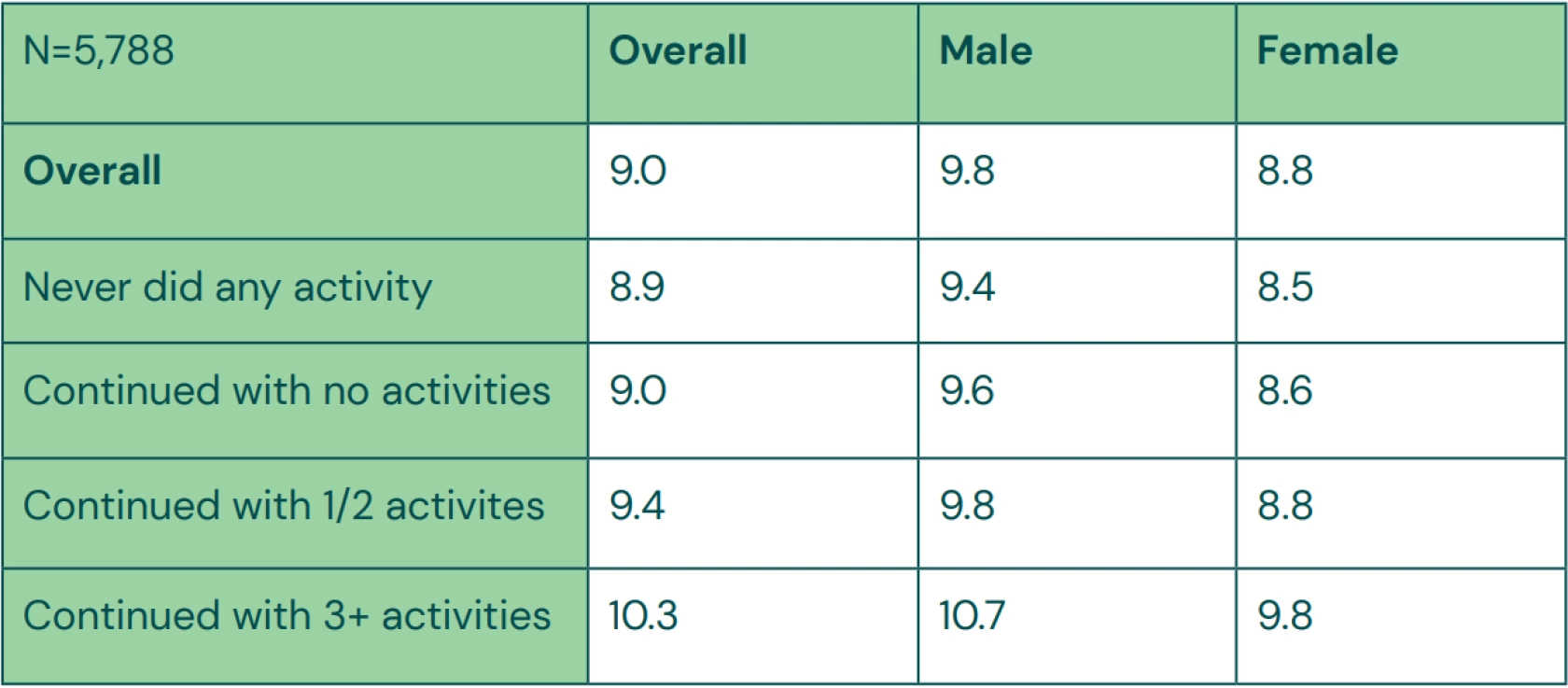

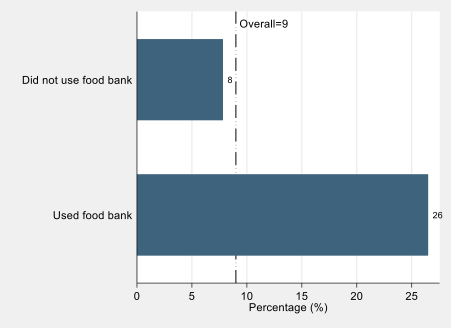

What have we learned about differences in catch-up activities between state and private schools? Evidence from the COSMO study finds that 53% of young people took part in at least one type of catch-up activity.

This figure was 54% for young people in state comprehensive schools, and slightly lower at 51% for those in independent schools. So, there is some evidence of differential catch up weighted towards the state sector, but it is not large. The definition of catch-up activities is wide, from extra online classes to one-to-one tuition. The latter of these is most likely to have had significant catch-up benefits (Burgess, 2020).

Focusing on the offer of tutoring, this was more likely for young people at independent schools (52% compared with 41% in state comprehensive schools). This is despite the government’s flagship National Tutoring Programme (NTP).

The NTP was meant to target this sort of provision to pupils who needed it most. Unfortunately, its reach was narrower than hoped, with an official evaluation report highlighting that ‘only around a half of school leads and staff felt that all or most of the pupils selected were disadvantaged’ (Lord et al., 2022).

That said, pupils in independent schools were less likely to have taken part in tutoring than those in state schools. Among independent school pupils, 23% said they had taken up this offer, compared with 27% in comprehensive schools. This seems to reflect pupils in private schools being less likely to feel that they needed this help, even if it was being offered. An equally important aspect of pupils’ ability to re-engage fully in their education is their mental health. Pupils attending private schools were more than twice as likely to report that their school mental health support was very good (26%) than state school pupils (10%) (Holt-White et al., 2022)

Figure 2: Whether participant agreed they had caught up with lost learning during the pandemic, by gender and school type

Source: COSMO Notes: N=12,149; analysis is weighted for survey design and young person non-response.

Despite catch-up efforts, pupils at state comprehensive schools were the least likely to think they had been able to catch up (34%). This compared with 58% of pupils at independent schools who felt this way. Almost half (46%) of pupils at comprehensive schools said they had not been able to catch up, while just over a quarter (27%) at independent schools felt the same.

Assessment during Covid-19

Because of the disruption to schooling, the government decided to replace GCSE and A-level exams with teacher assessed grades in 2020 (and centre assessed grades in 2021). Some adaptation was unavoidable, given the Covid-19 restrictions. But many highlighted the importance of retaining externally set and marked assessment (Anders et al., 2021).

Indeed, there is evidence of biases in teacher assessed grades that affect ethnic minority groups, those from lower income backgrounds, boys and those with special educational needs (Burgess and Greaves, 2013; Campbell, 2015). Top grades awarded in the two years in which teacher or centre assessed grades were used jumped up compared with the years before.

But the increase was most prevalent in private schools (Anders and Macmillan, 2022). The proportion of A grades awarded at A-level rose from 44.7% in 2019 to 70.4% in private schools in 2021 (compared with a rise from 24.1% to 42.1% in state academy schools).

Some of this could have been due to the differences in provision highlighted above. Yet, the particularly dramatic fall in grades for private schools in 2022 – a cohort that had more of their education disrupted – casts doubt on this.

We can also use findings from the COSMO study to understand differences in assessment practices between the sectors. Pupils in this cohort received teacher assessed grades for their GCSEs in 2021.

Private school pupils were more likely to say that their teacher assessed grades were better than expected than state school pupils. Likewise, they were much less likely to report that they did worse than expected. As with the changes in grades over time, this suggests a more generous approach to teacher assessed grades in private schools.

Whatever the exact mechanisms, these results represent a significant widening of the qualifications gap between state and private school pupils. This will have had – and will continue to have – significant implications for pupils’ future educational and employment trajectories.

Conclusion

Taken together, we can see that there are a range of ways in which disruption as a result of the pandemic has laid the groundwork for increased inequalities between pupils who attended state and private schools throughout their lives.

Existing gaps have been reinforced by differences in schools’ capacity to implement quick and effective responses at the outbreak of the pandemic.

It seems unlikely that these inequalities have been fully addressed with the fairly small differences in catch-up offerings – pupils themselves reinforce this view. And the use of teacher assessment in the place of usual exams appears to have baked in the results.

We will not know the full extent of the implications of this disruption for years to come. The COSMO study is designed to try to help us to do exactly that.

Some of the differences may unwind. For example, if some pupils’ grades were flattered more by teacher assessment than others, we would not expect this in itself to result in long-term productivity gains and hence to affect individuals’ wages (Wyness et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the knock-on effects (for example, access to university) may still reinforce the educational gap.

Ultimately, the early signs are not promising for inequalities in life chances between state and privately educated pupils as a result of the pandemic. We must not forget about the young people who have been disproportionately affected during this time.

As the pandemic subsides, it is easy to focus on ‘getting back to normal’, but in reality, extraordinary efforts are still needed to try to address these inequalities.

While important in itself, ensuring everyone is given the opportunity to achieve their potential in life is vital to the country’s productivity and, hence, everyone’s future economic prosperity.

This article was first published on the Economics Observatory on 5 December 2022.

Close

Close