Public health and digital communication in Cameroon in the time of COVID-19

By p.awondo, on 11 August 2020

If there’s one thing to remember about the way the Covid-19 global pandemic will affect the world, it’s the unprecedented way it is living and spreading in the digital world. This is such a novel fact that some have called it “a parallel epidemic”. This is characterised as much by an insurmountable number of fake news items as it is by a certain density of scientific information given by experts and commented on by analysts and pseudo-experts through digital platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp or even forums. This density of scientific information, often left to the layman to interpret, has often created confusion; but more than its density, there is also its changing and sometimes contradictory dimension that has fostered confusion and given rise to misinformation, conspiracy theories and fake news. All this is not new. In a way, the history of major epidemics is punctuated by these panics and uncertainties. What is really new is the way in which, through the mediation of social networks and platforms, the pandemic information has circulated, revolutionising, in passing, even the way leaders communicate in contexts where they sometimes resist ‘the digital’ or legislate against it. This is what happened in Cameroon, where the country’s administration has previously been reluctant to adopt digital means of communication, preferring secrecy. The government’s communication around Covid-19 has gone into digital mode in an unprecedented way and has mainly been centred around the use of Twitter to report on the evolution of the disease and inform Cameroonians.

Tweeting the coronavirus statistics

Cameroon, one of the most affected countries in sub-Saharan Africa, officially has 18,042 cases to date, 2,327 of which are still under treatment. 15, 320 people have recovered and there have been 395 deaths. The Minister of Health, very active from the beginning of the epidemic in Cameroon in March this year, no longer publishes daily figures on his Twitter account, as was long the case.

Before the first cases were declared on Cameroonian soil, the Minister had shown unprecedented proximity to the situation via his Twitter account. The first tweets concerned preventive measures, already taken in February, and also tried to reassure Cameroonians about the measures their government was putting in place when rumours were already circulating about the existence of cases in the country. Towards the end of February, the tweets started focusing on explanations about the occurrence of the disease on Cameroonian soil. Indeed, the Cameroonian minister had inaugurated a new mode of communication through tweets around the epidemic in a country where government administration continues to be done by decree and signed with a stamp as proof. Even if these administrative acts now circulate on Whatsapp, sometimes before being broadcast on national radio or in offices, the priority remains the paper act. The Cameroonian health minister’s investment in tweeting, therefore, appears like a UFO to Cameroon’s high administration.

Figures 1, 2 and 3: Tweets from the minister of Health before the first case of COVID-19 in Cameroon (1), tweets when the first case occurred (2) and tweets sent by the minister after Cameroon already had multiple cases, which aimed to reassure the nation about measures taken by the state (3).

The third series of tweets talks about the measures taken against the pandemic and what the government is doing to curb its spread – at this point, the virus was already on the country’s doorstep. Finally, once Covid had started spreading in the country, the tweets became concerned with the figures relating to the evolution of the pandemic.

This communication through tweets has fostered two rare things in the relationship between citizens and the authorities, especially health authorities, who have been publicly denounced in recent years for the inadequacies of the health system which were exposed by the AIDS pandemic, and especially for the inability to decrease the country’s infant mortality rate, which is considered too high, not to mention the corruption of personnel. The first positive point in relation to the communication coming from the Ministry of Health is proximity. By addressing citizens directly through tweeting, even though Twitter is far from being used by a large majority of Cameroonians, screenshots of the minister’s tweets quickly made a detour via WhatsApp and spread throughout the country. The first tweets were, therefore, ‘welcomed’ by the population via commentators and part of the press.

The second positive point was the dimension linked to the duty to democratise information and the principle of accountability to the people (two core principles of the republic). The idea that it is the minister’s duty to inform Cameroonians about the country’s health situation on a daily basis is banal at first glance, but not so common in the context of Cameroon, so the minister’s action initially made people forget about how hesitant the administration had initially been about closing borders (it was this hesitation that eventually led to the first cases). Subtly, however, some of the minister’s tweets alluded to the “irresponsibility” of travellers arriving into Cameroon and refusing to comply with the isolation measures, thus endangering Cameroonian lives. These tweets, which came at the time when the epidemic exploded, during April and May, rekindled the stigmatisation of travellers, often Cameroonian, who were known as “coro-mbenguists” (people living in Europe and potential corona carriers) in the context.

Tweets, fears and backlash

The minister’s tweets, initially hailed for their clarity and frequency, gradually found themselves at the heart of a controversy. There are three reasons for this. The first is related to the initial focus on the count of tested cases of travellers arriving from Europe. This was considered to be stigmatising because the press was beginning to relay the idea that the diaspora is responsible for the spread of the disease in Cameroon.

A second reason is related to the fear and psychosis created by the daily count of the minister’s tweets. With the number of positive cases increasing at an exponential rate, making the figures public has created, according to some analysts, significant stress among the population, who do not know what to expect in the coming days, especially since the executive decreed partial containment measures taken in mid-March were received in a mixed manner by a population with low incomes and dependent on the informal sector and therefore dependent on being present in the streets. These daily figures, which the citizens helplessly see going up by the day, echoed those in Europe, particularly in Italy and France, whose chaotic management of the pandemic mirrored the idea of an almost certain death for a large number of people. Beyond the nationalist rhetoric that I mentioned in a recent blog, the conversations on Whatsapp groups were marked by panic and a kind of inevitability of fate that can be summed up in the phrase “if Europeans, with the tools and powerful medicine die so much; what will happen to us? ». These reactions contrast with the analyses of public commentators who, faced with the slow spread of the virus on the continent, show a courageous and imperturbable Africa in the face of the pandemic. In reality, on the streets of Yaoundé, WhatsApp groups are overcome by anguish and fear. This panicked fear is reflected in certain recurring expressions in the discussions. In Yaoundé, in the face of the implacability of an event, people say: “we are waiting, what else can we do » (on attend on va faire comment).

The tone of anguish and panic, exacerbated by the macabre daily death count in Europe and circulating through social networks, with news items coming out of Italy and France, which were under lockdown and where life had stopped, forced the Minister of Health to change his communication strategy:

Fig 4 tweet about the decision to change the Ministry of Health’s communication strategy and stop declaring the number of new cases and deaths (7th April 2020).

On the 9th of April, the online press reported that, after giving in to constant requests from numerous followers (there are 71,000 of them), the Minister would no longer tweet the same way as before, announcing the following: “Very sensitive to the new direction you wanted to give to our communication, I will therefore From now on, I will endeavour to publish only information on the development of our strategy, serious cases, cured cases, deaths, and barrier measures”.

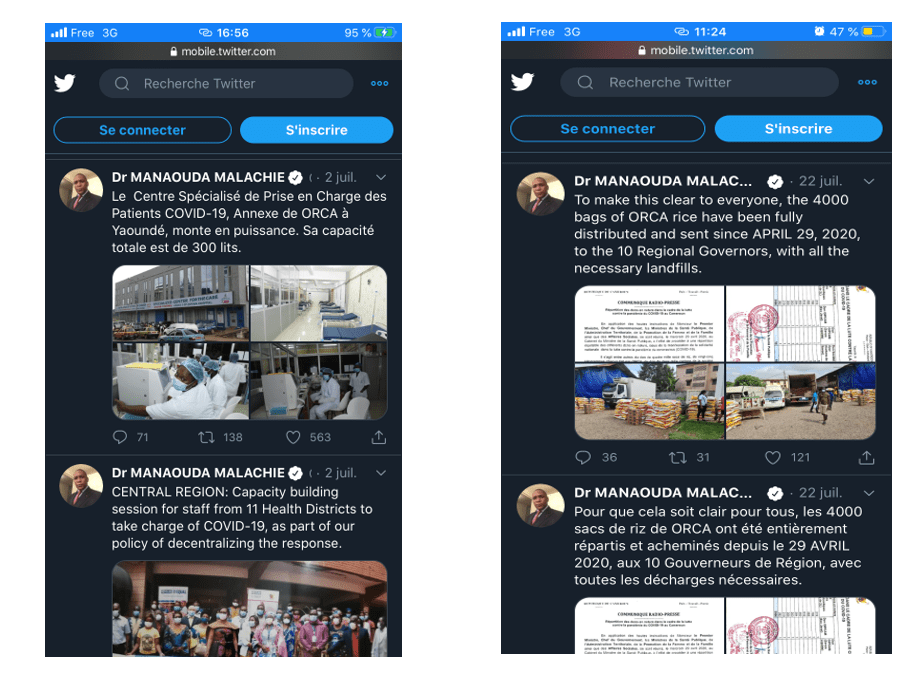

Although the Minister kept his commitment for a few days, he eventually returned to his more usual tweets, giving his followers the number of new cases and deaths. A third point to note as a backlash to the tweets is that the Minister of Health became popular at the beginning of the epidemic because of the novelty of reporting to the population. However, this popularity is not appreciated by all, and Cameroonians who are not used to government transparency will demand it to the end, especially with regards to the management of the special Covid fund, endowed with tens of billions of CFA francs (Cameroon’s currency) by the country’s Head of State. This turning point is materialised in the tweets where the minister highlights the government’s “achievements” such as measures taken to improve patient care or boost preventive measures.

But the card of transparency played by the minister does not really seem to bear fruit, because to date, he is under the cloud of accusations of misappropriation of public funds allocated for the pandemic, rumours of which pervade the entire Cameroonian web.

In the end, two observations can be made: the first concerns the innovative dimension of digital crisis communication in a context where opaqueness is the norm. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has revolutionised the links that institutional health actors can have with their populations because information (both good and bad) circulates through social networks so much, that leaders have to provide clarity if they do not want to be overwhelmed by the circulation of misinformation, fake news and rumours of a conspiracy involving them. One such conspiratorial rumour is, of course, that international pharmaceutical companies and the local government are plotting to spread the fear of the pandemic in order to aid the vaccine business. From an information democratisation perspective, there has thus been an advance in propagating the values of the republic in the Cameroonian context, with the government playing its part for once. A second observation illustrates at least one limit to this advance, namely that even if the government’s management of information puts the public’s interests first and tries to do so in a way that reaches as many people as possible, this does not guarantee that tensions and anxieties related to the socio-economic and epidemiological context will be minimised. On the contrary, in the face of the epidemic, uncertainties are growing. At the same time, Cameroonian citizens have rarely had the opportunity to hold their public health authorities to account in this way. This has made the COVID-19 pandemic not only a test for democracy but also the laboratory in which it is made.

Fig 5 & 6: tweets on governmental actions with regards to practicalities and capacity building in the fight against Covid 19 (5) and public statement after a controversy over the misappropriation of a rice donation by a private economic operator (6)

Close

Close