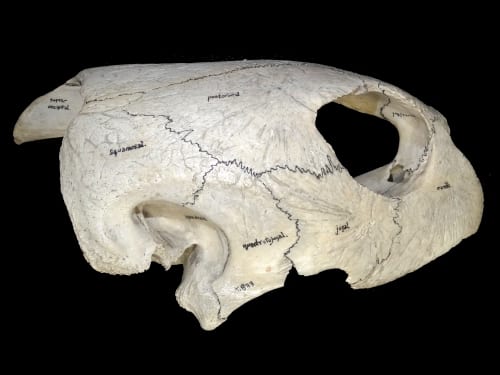

Specimen of the Week 217: annotated green turtle half-skull

By ucwepwv, on 7 December 2015

This week I’ve picked a specimen to talk about that is being used in comparative zoology practicals at the moment. I chose it because it has been helpfully labelled to show each of the bones which fit together to form the remarkable piece of biological architecture that is the skull. So this week’s Specimen of the Week is…

**an annotated green turtle (Chelonia mydas) half-skull**

Heroes in a half-skull

Cutting a skull in half in order to see inside may seem destructive, but it can open up a wealth of information about what’s going on inside a species’ head – at least structurally, it sadly can’t provide that much insight into the animal’s hopes and dreams. What it can give you is an idea of the general shape and size of the brain (not very big in this case); how teeth are attached to the jaw (although since modern turtles are all toothless, not in this case); how thick or thin the bones of the skull are (pretty darn thick in this case), and of course how the skull is adapted for those things that make it possible for animals to survive, from sensing the world to feeding themselves.

Cowabunga dude!

As you probably already know, pizza is not on the menu for green turtles. Normally they feed on marine plant material, like kelp and seagrass which they crop with the horny beak that covers the bones of the upper and lower jaw (mainly the maxilla, premaxilla, vomer and palatine in the top jaw, the dentary in the lower, if you want specifics). To be able to feed underwater they have a bony secondary palate (formed largely by the vomer and palatine), which allows them to separate their air intake from their food intake, so water doesn’t get into their lungs.

Inside the skull there are other adaptations for an extreme surfer mode of life. Part of the space behind the eye and alongside the brain just on the other side of the parietal bone, houses the salt glands. This organ plays an important role in removing excess salt from the turtle’s food and the seawater it swallows, secreting slimy and super-salty tears from the eyes. This helps maintain the right balance of salts, helping to prevent organ failure from osmotic shock.

Turtle power

On the outside of the skull, the relationship between various bones that create gaps in the skull have been used to address some very different questions about the evolutionary relationships of all ‘reptiles’, although these can be tricksy characters. Historically the turtles were assigned to the group Anapsida, defined by the lack of (‘an-‘) an arch (‘-apsis‘) in the side of the skull near the temples, which you see in the skulls of other groups of ‘reptile’. This was once considered a primitive condition, from near the base of the tree of ‘reptiles’, but these days there is quite a bit of debate about how good this feature really is for understanding relationships.

After all, although turtles are the only living group that have this character, they are pretty unique in several other ways, such as in having a carapace and shoulder blades inside their rib cage (seriously, think about how weird that is). The results of various molecular studies have supported the idea that turtles are actually part of the main ‘reptile’ family tree, so it may be that the anapsid condition is just a weird feature of turtles, that has been muddying the waters of ‘reptile’ systematics since the 1930s – how about that for turtle power?

Paolo Viscardi is the Curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Specimen of the Week 217: annotated green turtle half-skull”

- 1

Close

Close

![Green Sea Turtle grazing seagrass at Akumal bay © P.Lindgren 2013 [CC BY-SA 3.0]](https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/museums/files/2015/12/500px-Green_Sea_Turtle_grazing_seagrass.jpg)

[…] endangered and protected by international law, and you can find out more about the loggerhead and green turtles in our previous […]