Specimen of Week 214: Fossil Vertebrae

By Tannis Davidson, on 16 November 2015

In the spotlight this week is a specimen that is currently experiencing it’s ‘busy season’. The Grant Museum collection is widely used in teaching at UCL and the Museum is home to many specimen-based practicals. For example, during term 1 in 2014, there were 34 practicals using over 600 specimens by 1400 students.

Amidst this flurry of activity, certain specimens catch the eye. Is it that they are finally freed from the safe-keeping of their fossil drawers and have their moment to shine? Could it be that they are used over and over and over again to illustrate a turning point in evolution so critical that repeat viewings are essential? Or is it that the specimen is quite simply, an attractive object in itself, perhaps a worthy contestant in a specimen beauty contest?

This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

**Dimetrodon fossil vertebrae**

1. Appearance

This little array of vertebrae never fails to impress. Opening its box reveals the bag containing the vertebrae. At which point there is a moment of trepidation for the specimen is not clearly visible inside the bag. It’s there, but you just cannot see it through the world’s most be-dusted, pitted (yet still-robust) polyethylene bag. Usually baggies of such appearance yield the decrepit remnants of a specimen formerly known as ‘being in one piece’ but now more aptly described as ‘had a career-ending fall’. Yet such low expectations of X1111’s reveal are quashed as out pop nine spotlessly clean, beautifully-defined vertebrae.

2. Talent

Each autumn term X1111 is used in two GEOL2009 Geology Vertebrate Palaeontology and Evolution practicals illustrating vertebrate structure. The student handout indicates that this specimen ‘provides a good opportunity to learn some of the basic features of amniote vertebrae’. Indeed, the excellent preservation of the vertebrae allow for the identification of the following features: the centrum, the neural canal, the spinal canal, the transverse processes, the neural spine and the zygapophyses.

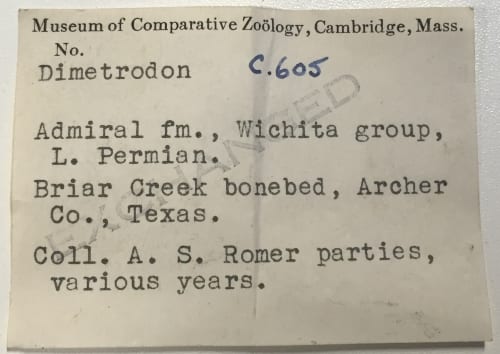

3. Pedigree

X1111 really is the full package. It was collected by Alfred Sherwood Romer, (the American palaeontologist, biologist and specialist in vertebrate evolution) from the Briar Creek bone bed in Archer County, Texas. The information label with the specimen indicates that it came from the Museum of Comapartive Zoology, Cambridge, Mass. (Harvard) where Romer was director from 1946. Interestingly, the label has ‘EXCHANGED’ stamped across it – which begs the question ‘exchanged for what’? Here the paper trail runs cold. However, given the quality and perpetual usefulness of X1111, I’m happy to believe that the Grant Museum got the better end of the deal.

4. Personality

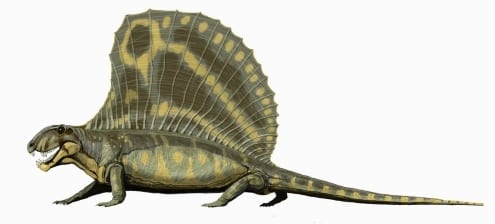

As a specimen, there’s no doubt that X1111 has a certain charm. But what about Dimetrodon itself? Hailing from the Early Permian period (295-272 million years ago), Dimetrodon is possibly the most recognisable dinosaur-like creature that is, in fact, not a dinosaur but a pelycosaur. Featuring a tall sail on its back formed of elongated spines, Dimetrodon superficially looked like a reptile. It does, however, belong in the clade called Synapsida – which includes mammals and ‘mammal-like reptiles’ – defined by sharing primitive characteristics such as distinctive temporal openings and other skull features. Therefore, Dimetrodon is more closely related to mammals than reptiles, though it is not a direct ancestor of mammals (1).

5. Moment of truth

Now if this were a real (specimen) beauty contest, the contestant would be faced with answering the judge’s questions. For Dimetrodon, there seems to be one enduring, persistent question that has remained unanswered since the genus was first described in 1878: what was the sail for? Over the years there have been numerous theories as to the purpose of the sail including:

– thermoregulation (using the sail to warm the body from the sun’s heat) (2)

– acting as a sail to catch the wind when the animal was in water (3)

– stability when walking (4)

– threat or courtship displays (5)

– a combination of any of the above

Alas, X1111 has yet to reveal this secret so for now, the sail remains an enigma.

Dimetrodon giganhomogenes, autor – Bogdanov,2006 CC BY-SA 3.0

References

1. Angielczyk, K. D. 2009. “Dimetrodon is Not a Dinosaur: Using Tree Thinking to Understand the Ancient Relatives of Mammals and their Evolution”. Evolution: Education and Outreach 2 (2): 257–271. [online] http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12052-009-0117-4 (accessed 2015-11-09)

2. Romer, A. S. and L. I. Price. 1940. Review of the Pelycosauria. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, Special Papers No. 28.

3. Florides, G.A.; Kalogirou, S.A.; Tassou, S.A.; Wrobel, L. 2001. “Natural environment and thermal behaviour of Dimetrodon limbatus”. Journal of Thermal Biology 26 (1): 15–20. [online] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030645650000019X (accessed 2015-11-09)

4. Rega, E.; Sumida, S.; Noriega, K.; Pell, C.; Lee, A. 2005. “Evidence-based paleopathology I: Ontogenetic and functional implications of dorsal sails in Dimetrodon”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (S3): 103A. [online] http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724634.2005.10009942 (accessed 2015-11-09)

5. Bakker, R. T. 1970. Dinosaur physiology and the origin of mammals.

Evolution 25:636–658.

Tannis Davidson is Curatorial Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

Close

Close