Pottery Project Guest Blog: Pondering Petrie’s Broken Pots

By Alice Stevenson, on 7 March 2014

Guest Blog by Grazia di Pietro

In the second in our series of different perspectives on Egyptian pottery Dr Grazia di Pietro, UCL Marie Curie Research Fellow, looks at what we can learn from incomplete fragments of prehistoric pottery.

For museum curators finding room in a gallery for exhibiting nice whole pots can be as challenging as trying to answer questions like: “What was their function, context of use, symbolic meaning?”. Answering these questions is also one of the objectives of pottery specialists researching in field projects or in ceramic analysis laboratories. However – needless to say – the pottery they have to deal with is often very different from what can be observed in a museum case.

Let’s go back for a moment to the initial issue: finding space for our pots! Well, they would occupy less room if broken in small pieces and (obviously) even less space if some of these potsherds were discarded or piled in a corner, irrespective of their previous location and sorting… We would eventually have created something similar to that which archaeologists frequently face in an excavation: tons of broken vessels (but still with great informative potential!).

Pottery piece: Rim sherd with red polished surface and white painted decoration (Petrie’s “Cross-Lined ware” C-Ware)

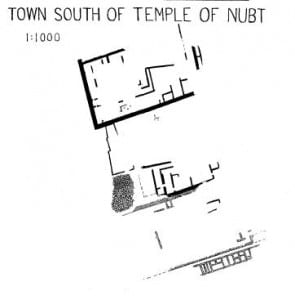

This is also the scenario in which I found myself when, for my doctorate research, I examined materials, including pottery, from an expedition of the former “Istituto Universitario Orientale” (Naples, Italy) conducted in one of the sites previously excavated by Petrie at the end of the 19th century, “South Town”, the settlement site associated with the Predynastic cemeteries of Naqada, whose main phase of occupation falls roughly between 3400 and 3200 BC.

A number of pots from the excavations of Petrie at this site are presently kept at the Petrie Museum and are catalogued with the numbers UC5310–23. Though small, this collection is a precious source of all sorts of information from chronology to pottery technology.

In terms of dating, for example, the presence of both red-slipped potsherds with white painted designs (e.g UC5311), typical of the earliest stages of the Predynastic, and of buff-coloured pottery with decoration painted in red (e.g. UC5313), prevalent in the later stages, suggests that part of the settlement excavated by Petrie was occupied over a long period of the 4th millennium BC.

The few pots from South Town reflect also the variety of resources and technologies skilfully employed by the Egyptian potters at this point in prehistory. Clay sources exploited were located close to the river (Nile silts), which were further refined and used with or without the addition of other material (UC5310–11, 17 and UC5319–22 respectively), or in the wadi beds present in the deserts bordering the Nile valley (marls like UC5312–16, 23). The clay paste was subsequently shaped by the potters into a variety of forms, such as bowls (UC5313, UC5318, UC5323), beakers (UC5317), jars (UC5320, UC5322), bottles (UC5320), which were intended to fulfil different purposes in everyday life, for example for food processing/serving (bowls) and for transportation/storage (jars). Before the firing process, vessels could have been subjected to further treatments: their surfaces being coated with a red ocherous or whitish slip, further polished and decorated with white or red painted designs (UC5310–17). The investment of labour and means involved in the whole production process of these vessels, from the selection of the clay to their firing, leaves little doubt that they were manufactured by specialised artisans.

But are these pots truly representative of the types of ceramic in use in the settlement of Naqada during the 4th millennium BC? Unfortunately, it is unlikely this would be the case. The composition of this pottery collection reflects more the choice of the archaeologist, than the assemblage from which it originated. Indeed, fine ware and decorated pieces (UC5310–17) outnumber pots made of rough-faced, chaff tempered Nile silt fabric (UC5317-22), while we know that the majority of the pottery usually found in Predynastic settlement contexts is of the second type.

Today archaeologists collect and record the entire ceramic assemblage retrieved from a given context, in order to estimate the proportions of various types as it would have existed in the past. This approach can lead to a clearer idea of the range of activities that might have been carried out in a site and, potentially, differences in function or chronology in different parts of a site or from site to site. These are some of the topics that I am currently trying to investigate within a research project hosted at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology and by considering ceramic samples (mainly potsherds!) from the settlement site of Naqada and other regions of the Nile Valley. However, when my eyes (and my soul) are tired of dealing with brokenness, I can easily pop over the Petrie Museum and feast on the intact shapes of the Predynastic pots, their intense colours, shiny polished surfaces and imagine how many industrious hands and creative minds might have been behind these small (…but space-consuming) pieces of superb craftsmanship.

Close

Close