Art Research in a Science Museum?

By Mark Carnall, on 10 May 2013

It seems to be a week for thinking about Art vs. Science this week. Of course the whole idea or art vs. science is a fallacy but increasingly I meet artists and scientists who want to live up to the stereotype of being in either camp and rejecting outright the other one. As a university museum we work very hard to ensure that our collections support the research of the academic community not just here at UCL and it isn’t just science researchers who are ‘allowed’ in.

Natural history and art have a shared history and for a long time were the same thing. Trace the origins of an interest in the natural world and biology back to its roots and description, observation, inspiration and illustration are natural history. You couldn’t prise the ‘art’ or the ‘science’ bits out of it without undermining the whole endeavor. This tradition continues today, if we think about the Wildlife photographer of the year, the imagery employed by conservation agencies, the latest Wellcome collection exhibition, the works of Mark Dion or even the plates and graphs from scientific journal papers they can be considered both art and science. Particularly, with the pervasive use of the Internet, visual media is increasingly how we communicate our ideas, agendas and passions. Be it a powerful image that sums up the plight of Orang Utans, a meme that causes us to chuckle over a tea break or the sheer beauty of what is called ‘data porn’, that is, a nice infographic that shows rather than tells the story.

So on any given day at the Grant Museum we could have visiting scientific researchers who may be measuring the dimensions of a skull or looking for the differences between fossils. Alternatively we could have an artist creating an installation for our Foyer and we’re excited to see the reactions to the museum for our upcoming sculpture season collaboration with the Slade School of Fine Arts. Rarely is there a day where we don’t have an art group or individual artists sketching or photographing specimens on display. All of the above are equally valid uses of museum collections and this post follows a day out for one of our specimens down to the Royal College of Art.

A number of weeks ago, MA Sculpture student at the Royal College of Art, Claire Poulter approached the museum wanting to look at our elephant specimens. We have a number of elephant remains here not just the dried heart and the three skulls on display but a number of skeletal parts, a series of teeth, plaster casts, fossils, microscope slides and wet specimens (including a section through a trunk). Claire was interested in teeth so we arranged an appointment for her to come and see them.

Claire was inspired by elephant teeth because she heard that once elephants use up their finite teeth sets, they can, if otherwise healthy, starve to death. Elephants are also linked to memory and Claire was driven by exploring the origins of things. Where did these teeth come from and what role do they now have in a museum of zoology? Elephant teeth are also highly curious objects which is why we use them a lot here in our teaching and handling activities. Elephant teeth are very tactile and recognisable but at the same time alien and many of our visitors are amazed at the size, shape and weight of these teeth, particularly when they see how elephants have to carry around four of these dense, heavy teeth in addition to the two tusks they are sadly hunted for. Whilst Claire was here I accidentally slipped into science communication mode and started to bring out some of our specimens that show what makes up an elephant tooth including this series of tooth plates, the hard enamel plates that form the grinding surface in teeth which can be dissolved out of a tooth or found in the fossil record.

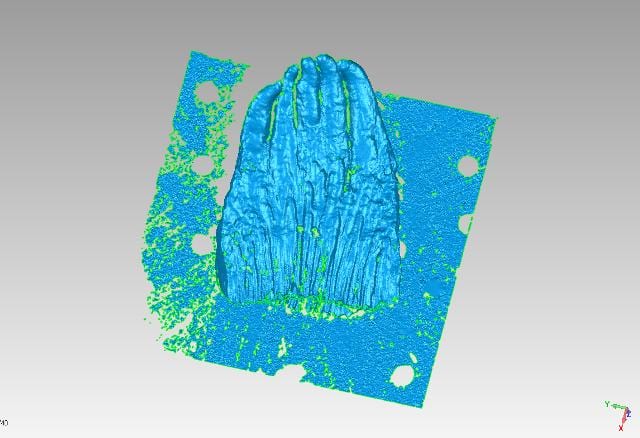

Claire was really taken with these tooth plates and was keen to incorporate teeth and these plates into her work. Initially we discussed making casts of some of our specimens but this puts specimens at increased risk of damage and can be quite invasive, particularly for subfossil and fossil teeth with are peppered with cracks and crevices. Instead, Claire modelled the tooth for a larger sculpture in iron and decided to scan the tooth plates to create a 3D model with which she could work with.

Last week I packed the objects up and whisked them over to the Rapidform facility at the Royal College of Art to scan them in. Whilst there technician Hannah Terry and Claire scanned in the tooth plates using a handheld scanner to create a 3 dimensional model.

I was also lucky enough to get a tour of the facility at the Royal College of Art and the ongoing link between art and science was very much on show. Not only was this the facility that produced the handling replicas at the Natural History Museum’s Treasures Gallery but there were various printed animal remains, human body parts from palaeoanthropological reconstructions of fossil remains and rapid prototype replicas of important specimens. Also scattered around the various machines at the facility were impossible printed abstract sculptures, engineering parts, printed designs for car parts and haunting human face masks printed in plaster, paper, titanium and a host of other substrates. Again, in this facility it’s impossible to draw the line between art and science or to say how one can possibly exist without the other.

I’m excited to see what Claire produces in the latest of the ongoing conversation with artists taking inspiration from the natural world and in turn those sculptures, prints, paintings, drawings and films inspiring the next generations of scientists and artists.

2 Responses to “Art Research in a Science Museum?”

- 1

-

2

Sculpture Season opens today | UCL UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 5 June 2013:

[…] is a certain way scientific museums do things. This project is a real collaboration between the (often deeply connected) worlds of science and art. We’ve had to think carefully about when to do things like an art […]

Close

Close

[…] chance would have it at the same time as we received research interest from the Royal College of Art, colleague Dr Zerina Johanson, researcher in the Earth Sciences Department at the Natural History […]