Specimen of the Week: Week Sixty-Six

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 15 January 2013

Having been suffering from Yersinia pestis (aka the Black Death) for the last few days, this morning I should first like to apologise for Specimen of the Week being a day late (I’m sure there were oodles of disappointed faces staring in disbelief at the lack of a new Specimen of the Week on their computers yesterday), and secondly introduce you to a specimen full of warm fuzzies to make aid my recovery. It is a species that is gorgeous to look at, completely loveable and has a delightful personality to make me feel better and cheer up any post-Christmas/New Year blues that may be festering in the audience. It isn’t related to poisonous reptiles, scary spiders, or bitey insects. Ladies and gentlemen, for your enjoyment, this week’s Specimen of the Week is…

Having been suffering from Yersinia pestis (aka the Black Death) for the last few days, this morning I should first like to apologise for Specimen of the Week being a day late (I’m sure there were oodles of disappointed faces staring in disbelief at the lack of a new Specimen of the Week on their computers yesterday), and secondly introduce you to a specimen full of warm fuzzies to make aid my recovery. It is a species that is gorgeous to look at, completely loveable and has a delightful personality to make me feel better and cheer up any post-Christmas/New Year blues that may be festering in the audience. It isn’t related to poisonous reptiles, scary spiders, or bitey insects. Ladies and gentlemen, for your enjoyment, this week’s Specimen of the Week is…

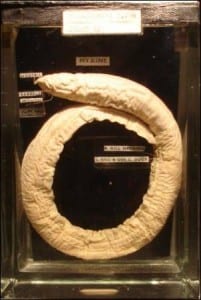

**The Hagfish**

1) As the attractive name ‘hagfish’ implies, these delightful creatures are a species of fish. If that name isn’t to your taste, they are also known by the equally pleasant sounding name of slime hag. Although they are fish, they are so primitive as to be jawless. Although officially classified as vertebrates, they confusingly have no real vertebrae but rather nodules of cartilage that make up a sort of pseudo-spine, or fake back-bone if you will.

2) Instead of going to the energy of growing jaws, hagfish decided to evolve two pairs of tooth-like rasps on a sort of tongue like appendage. As weird as it sounds, it works very well for them. Hagfish use their rasp covered ‘tongue’ to tear into the flesh of dead or dying fish and marine invertebrates. When vital-signs-challenged fish are in short supply, hagfish can implement a wonderfully slow metabolism to be able to survive for up to seven months without food. Rather them than me.

3) Why ‘slime’ hags? One of nature’s more obvious animal names, hagfish or slimehags can produce enormous quantities of sticky, jelly-like slime. Much like my nose over the last few days. Unlike me, who was doing it to rid myself of an infection, hagfish do it as a defense mechanism. If a predator grabs hold of a hagfish, it can rapidly secrete a layer of slippery slime, that envelopes the entire body and serves to reduce the predator’s grip to something out of a Carry On film. The hagfish can then clean itself by tying its body in an overhand knot and gradually sliding it down from the head to the tail. This scrapes off the slime leaving a clean and fresh hagfish, much like servants did for sweaty Roman officials in public baths.

4) A talent like knot-tying can’t be wasted and hagfish are keen to show off their skills whenever possible. So as well as cleaning themselves in this way, they also use their knot-tying ability to feed. By grasping a mouth full of flesh and then tying their body in a knot, hagfish are able to ‘spin’ the knot up the body towards the head, resulting in the head wrenching free, and bringing a mouth full of yummy dead flesh with it. We have neck muscles, hagfish have knots. Although hagfish are almost blind, they can locate their ‘prey’ using their superb senses of touch and smell.

A Pacific hagfish. (Image taken via ROV

in Astoria Canyon off the Oregon Coast in

2001. Taken from Wikimedia Commons)

5) Sadly for hagfish, and I’m inclined to say for South East Asians, hagfish are eaten as a delicacy in Japan and Korea. Presumably they’re cleaned of slime first. Their skin is also utilised and you can find yourself an ‘eel leather’ or ‘eelskin’ purse if you should be sufficiently possessed to do so.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Museum Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

One Response to “Specimen of the Week: Week Sixty-Six”

- 1

Close

Close

Yay! Finally you concede that hagfish are beautiful! ;o)

(I’m choosing to assume that you are certainly, definitely not being sarcastic, dear me no.)

It is also hypothesised that they use their slime to clog up a potential predator’s gills. The head-to-tail knot serves to clear their own body of the slime so that their own gills don’t get similarly blocked. If necessary they are able to clear their own gills of slime by sneezing – the only fish (to my knowledge) that is able to do so.