East Scotland Deaf Draughts Champions – 1900

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 8 April 2016

Close

Close

Information on the UCL Ear Institute & Action on Hearing Loss Libraries

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 8 April 2016

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 1 April 2016

Dorothy STANTON WISE, (1879-1918) was a talented sculptor. Born on the 20th of October, 1879,* one of four children, Dorothy was deaf from birth. Her birth name was Dorothea rather than Dorothy. Her father who ran a small boarding school with his wife, taught mathematics, her mother Elizabeth taught Dorothy to draw. Elizabeth wrote an extensive article, “How a mother educated her own deaf child,” published in The Association Review in 1909.

Dorothy STANTON WISE, (1879-1918) was a talented sculptor. Born on the 20th of October, 1879,* one of four children, Dorothy was deaf from birth. Her birth name was Dorothea rather than Dorothy. Her father who ran a small boarding school with his wife, taught mathematics, her mother Elizabeth taught Dorothy to draw. Elizabeth wrote an extensive article, “How a mother educated her own deaf child,” published in The Association Review in 1909.

We had no fears about her until she was two years old. She cooed and laughed like any other baby, looked up when I entered the room, and was particularly lively and happy; but when she reached that age, and still only cooed and laughed, I was afraid she must be tongue-tied. The doctor soon settled that point, and, after a few minutes’ careful watching, broke to me what the real trouble was. He talked about my waiting a while, taking her to an aurist, and so on, and casually remarked, “I suppose you know now the deaf are taught to speak, and to understand by the movement of the lips.” I did not know; we had no deaf friends, and the matter had never interested me; but suddenly, at that one sentence, the whole horror of the shock fell away, and a future of infinite possibilities opened out. The doctor was kind and sympathizing; I stood by the window looking down the familiar street, but I saw all the old objects under a new light required for their interpretation to Dorothy, and her education began from the moment we skipped out of his doorway. (p.104)

When she was five she attended a kindergarten for two years (circa 1886), but then inexplicably says, “there was no school for the deaf within fifty miles of us” (p.104) – yet Margate school was only a few miles away. At any rate, Elizabeth consulted the oralist teacher in Northampton, Mr. Arnold, who gave her some help in learning his methods of education. When they moved to London, Dorothy had a short course of lessons in lipreading every spring at the Fitzroy Square School. Straight after kindergarten Dorothy “went twice a week to a school of art for the usual course of freehand and model drawing” (p.106). She decided to pursue art, wanting to study under Lantéri in the Royal College of Art. To qualify, the whole family contributed to her art education, her father teaching her perspective, her mother helped with lessons in anatomical drawing that Dorothy developed further on her own, and her younger brother sat and worked with her on geometrical drawing (p.107). After five years study under Lantéri she obtained the sculpture degree in 1906, the only girl in her year to do so.

When she was five she attended a kindergarten for two years (circa 1886), but then inexplicably says, “there was no school for the deaf within fifty miles of us” (p.104) – yet Margate school was only a few miles away. At any rate, Elizabeth consulted the oralist teacher in Northampton, Mr. Arnold, who gave her some help in learning his methods of education. When they moved to London, Dorothy had a short course of lessons in lipreading every spring at the Fitzroy Square School. Straight after kindergarten Dorothy “went twice a week to a school of art for the usual course of freehand and model drawing” (p.106). She decided to pursue art, wanting to study under Lantéri in the Royal College of Art. To qualify, the whole family contributed to her art education, her father teaching her perspective, her mother helped with lessons in anatomical drawing that Dorothy developed further on her own, and her younger brother sat and worked with her on geometrical drawing (p.107). After five years study under Lantéri she obtained the sculpture degree in 1906, the only girl in her year to do so.

The family ended up living in Hendon, and she remained with her parents, working on commissions.

She died on Christmas Day 1918**, possibly the victim of the influenza outbreak. Regular readers may recall the words of Yvonne Pitrois – “My heart was nearly broken when I heard of the passing away of Miss D.S. Wise!”

There is certainly sufficient material on Dorothy to make an interesting article, especially if the writer has an interest in art and can track down her original works. Perhaps the Royal College of Art Archive has interesting records of her.

**[not 1919 as Lang says – see probate records and death index]

*Dorothy Stanton Wise, Døves Blad, No.3, 1922, p.4-5

*Dorothy Stanton Wise, Døves Blad, No.3, 1922, p.4-5

The Late Dorothy Stanton Wise, A.R.C.A., Ephphatha 1919 no.42 p.550-1

Lang, Harry C. & Meath-Lang, Bonnie, Deaf Persons in the Arts & Sciences, 1995, p.381-4

Pitrois, Yvonne, Dorothy Stanton Wise, The Silent Worker, 1916. 28 (7) p.121-2

Ray, Cuthbert Hamilton, A Clever Deaf Sculptor, BDT 1911, vol 8 no.90 p121-3Roe, W.R., Peeps into the Deaf World, p. 1917

Wilson, Miss Edith C., Note to “How I Became a Sculptor”, The Volta Review 1913, Vol.15, 406-7

Wise, Dorothy Stanton, How I became a Sculptor, The Volta Review 1913, Vol.15, 403-5

Wise, E. A., “How a mother educated her own deaf child,” in The Association Review, 1909, vol.11 p.103-8

http://dspace.wrlc.org/view/ImgViewer?url=http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/manifest/2041/36909

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 22 March 2016

In the 1920s eugenics was a very hot subject, an area of much concern to Percival Macleod Yearsley (1867-1951). Percival was a cousin (twice removed) of James Yearsley the great aural surgeon. Yearsley was formerly consulting aural surgeon to St. James’ Hospital, Balham, and to the London County Council. He died at Gerrard’s Cross on May 4, 1951 at the age of 83. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and the Westminster and London Hospitals. In 1893 he was appointed to the staff of the old Royal Ear Hospital in Soho, becoming senior surgeon, and

In the 1920s eugenics was a very hot subject, an area of much concern to Percival Macleod Yearsley (1867-1951). Percival was a cousin (twice removed) of James Yearsley the great aural surgeon. Yearsley was formerly consulting aural surgeon to St. James’ Hospital, Balham, and to the London County Council. He died at Gerrard’s Cross on May 4, 1951 at the age of 83. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and the Westminster and London Hospitals. In 1893 he was appointed to the staff of the old Royal Ear Hospital in Soho, becoming senior surgeon, and

he was the first aural surgeon to the London County Council, for whom he carried out important investigations among school-children. He also interested himself in the welfare of deaf-mutes. A man of many interests, Macleod Yearsley wrote some delightful fairy tales, studied the story of the Bible, discussed the sanity of Hamlet and doctors in Elizabethan drama, took a scientific interest in the Zoological Society, translated Forel’s Sensations des insectes, and was an archaeologist of repute. In his own specialty he wrote a Textbook on Diseases of the Ear (1908) and another on Nursing in Diseases of the Throat, Nose and Ear. Later he became greatly interested in the Zund-Burguet electrophonoid treatment of deafness, on which he wrote a monograph in 1933. Energetic, open-minded, and many-faceted, he was looked upon as rather a stormy petrel by his contemporaries; but he mellowed with time, to be regarded with respect and admiration by otologists of today. (Obituary in the Lancet, 1951)

The letter, a follow up to a much longer letter signed by a number of notable people, appears in a scrap page from Ernest Ayliffe’s collection of various odd documents and letters, with associated cuttings, and the page is dated ‘Feb 22/29’. The year was 1929, the newspaper the Daily Mail.

Breeders of the Deaf

Sir,- For the past twenty-one years I have been advocating the sterilisation of those who are responsible for the perpetuation of a considerable section of our “deaf-mutes.” But hitherto such advocacy has fallen upon deaf ears.

There are numerous examples in our deaf schools all over the country of born deaf children whose disability is due to what is known as “true hereditary deafness,” a condition which, in its propagation, follows the Mendelian theory.

Dr. Kerr Love, of Glasgow, and I have published for years past a considerable amount of work upon this question, and have shown that, while there are hearing carriers of deafness whom it be difficult to sterilise, owing to the practical impossibility of recognising them until they produce deaf children, those who are born hereditarily deaf breed true, and can be safely expected to do so.These are the cases which require sterilisation, and I have a considerable number of family trees showing this sure method of perpetuation of deafness.

I need not expatiate upon the advantage to the race and to the State if this form of deafness could be eliminated, but I would point out that the education of a normal hearing child costs approximately £5 18s., while that of a deaf child is £69 18s. 10d.

This gives an additional reason for sterilisation of the unfit, and it is satisfactory to see that the letter published contains the names of bishops as well as of men of science.

MACLEOD YEARSLEY, F.R.C.S., F.R.A.I.

81 Wimpole street, W.1.

As you see, Ayliffe added some comments –

Comments

Wish to call attention to this very damaging letter to the cause of the Deaf.Whatever the merits of the system it is a brutal one.

May be justification for it in a few cases- but very few.

Why Deaf & Dumb! Why not blind. You get some cases to my certain knowledge – generations of them (in few cases likewise)

Why not M.Ds?

Why not the vicious?

Why not criminals?

[pencil] Difficulty of appeal [pencil]

Our appeal for the Deaf is very seriously jeopardised by such a letter.

Can anything be done by the committee to counteract it?

[pencil] Implications by quotation from Kerr Love

Ought we to repudiate the whole thing or let Yearsley get away with his self advertisement? [pencil]B.D.D.A. – [pencil] Indignation – but –

N.I.D.

Ayliffe’s comment there seems to expose Yearsley. His understanding of the new science of genetics does not seem to be great. Despite his other certain talents, in this letter he comes across as a shameless self-promotor, a mere shadow of his relative.

Percival Macleod Yearsley Lancet. 1951 May 19;1(6664):1130.

Updated 23/12/2016 with photograph of Yearsley from Teacher of the Deaf

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 17 March 2016

Ann Denman was the nome de plume of Katie E.M. Croft, a teacher of the deaf at the Royal School for the Deaf, Manchester. I cannot add any interesting biographical details about her as I have not definitely identified her date or place of birth or death, though it is possible she is Katharine Elizabeth M. Croft, born in Derby in 1895. Unfortunately we do not have a complete record of the Royal School annual reports, which were very full and included pictures. Miss Croft appears on the list of staff for Clyne House, the part of the Royal School for the juniors, under nines, from at least 1925 to the war. She was one of the resident teachers, following on from the first resident teacher at the school, Irene Goldsack, who married Alexander Ewing.

Ann Denman was the nome de plume of Katie E.M. Croft, a teacher of the deaf at the Royal School for the Deaf, Manchester. I cannot add any interesting biographical details about her as I have not definitely identified her date or place of birth or death, though it is possible she is Katharine Elizabeth M. Croft, born in Derby in 1895. Unfortunately we do not have a complete record of the Royal School annual reports, which were very full and included pictures. Miss Croft appears on the list of staff for Clyne House, the part of the Royal School for the juniors, under nines, from at least 1925 to the war. She was one of the resident teachers, following on from the first resident teacher at the school, Irene Goldsack, who married Alexander Ewing.

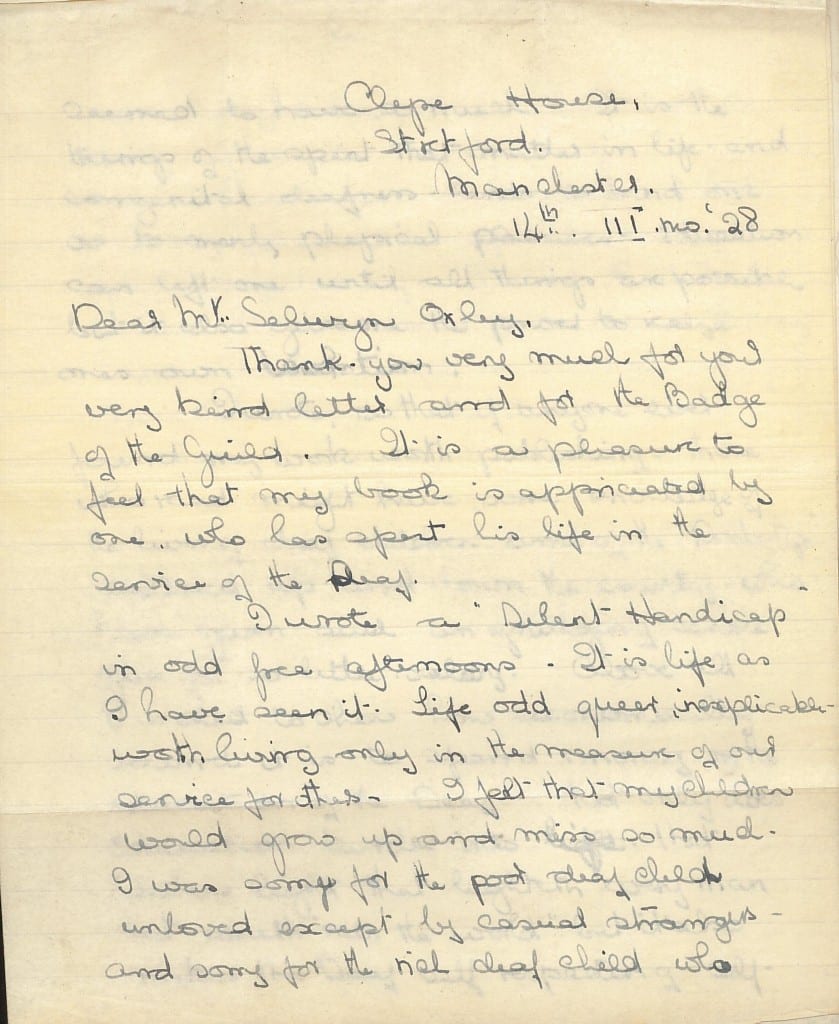

Why are we particularly interested in her rather than Misses Elliott, Baker or Cross, her fellow teachers in 1925? Well, she wrote a novel, A Silent Handicap, published by Edward Arnold in 1927. The novel follows the lives of three children who were born deaf, an illegitimate orphaned girl, a boy from a poor background, and a girl with wealthy parents. Our copy has a promotional leaflet with review excerpts, and Selwyn Oxley’s inimitable black inky scrawl. He had a brief correspondence with Katie Croft, which is stuck into the front of the book. First there is a three page letter from the 14th of March, 1928, then a couple of short notes congratulating the Oxley’s on their marriage, and Kate Oxley’s second book being published. Oxley had sent her a Guild of St. John of Beverley badge. He seems to have scattered them around, for I have come across other mentions of people receiving one.

He had a brief correspondence with Katie Croft, which is stuck into the front of the book. First there is a three page letter from the 14th of March, 1928, then a couple of short notes congratulating the Oxley’s on their marriage, and Kate Oxley’s second book being published. Oxley had sent her a Guild of St. John of Beverley badge. He seems to have scattered them around, for I have come across other mentions of people receiving one.

A few quotations from the novel will give a flavour of the story.

“She’s deaf and dumb, you know,” said Mr. Searle, feeling sorry for the woman and the child.

“Fiddlesticks!” said the Doctor. “You can train a puppy, why not a deaf child? […]” (p.8)

School work began with prayers. Geoff stood sullenly between two children. A grown-up person had pushed him there and shaken her finger at him, and as he had always associated a sound cuff with the breaking of the law as laid down by finger-waggers, he stood where he had been put and frowned angrily. (p.30)

Chapter 19, A Proposal, describes how Mary and Geoff, the two children in the excerpts above now adults, get engaged: Geoff has given Mary a watch as a present –

Her eyes sparkled. She looked up at Geoff to thank him. He did not wait for her thanks, but caught her in his arms, and rubbed his mouth against her neck and cheek. He had never learnt to kiss. His lips sought her skin as the horse noses its mate. Mary bent back her head that their faces might meet. She rubbed her cheek against his.

It was a strange proposal of marriage. (p.194)

This was the 1920s, and eugenics rears its head –

“You should say until Prince Charming comes,” said her father. […] He’ll be coming along and marrying you.”

“Marry me? No one will ever marry me, said Sally, shaking her pretty head. I shall not marry , Daddy. I shall live for ever and ever with you.”

“I wish I could think so, but I can’t,” said Sir Patrick.

“Yes, I shall,” said Sally. She had been reading a book on eugenics, and spoke with the finality of youth. “Deaf people shouldn’t marry.”[…]

“Love and common sense don’t go together, Sally,” he said, but Sally had stooped to get a piece of coal from the box, and had not seen him speak. (p.231)

Katie Croft says in her letter to Oxley,

I wrote a “Silent Handicap” in odd free afternoons. It is life as I have seen it. Life odd queer, inexplicable – worth living only in the measure of service for others. I felt that my children would grow up and miss so much. I was sorry for the poor deaf child unloved except by casual strangers – and sorry for the rich deaf child who seemed to have so much. It is the things of the spirit that matter in life – and congenital deafness tends to bind one so to mainly physical pleasures. Education can lift one until all things are possible but it also gives the power to realize ones own isolation.

I wrote, so that if anyone ever found my work worth publishing, those who read might have some knowledge of the lives of deaf children, and of the “Dockerty’s”* scattered up and down the country, who have given such ungrudging service often for so little salary. Above all I wished to show how economically sound it is to spend money on the education of the Deaf. Not only does education kindle into life that Divine “light that lighteth every man that cometh into the world” but it also makes the Deaf self respecting, self supporting citizens: a help not a drag upon the community.

If you can add any information about Katie Croft, please do in the comments field below. The novel is probably hard to find – at the time of writing there is one available on Alibris. We have a loan copy as well as the one with the letters.

If you can add any information about Katie Croft, please do in the comments field below. The novel is probably hard to find – at the time of writing there is one available on Alibris. We have a loan copy as well as the one with the letters.

For a picture of Clyne House search here https://apps.trafford.gov.uk/TraffordLifetimes.

It seems that the house was a hospital during the Great War.

*Dockerty was a character in the novel

Thanks to Geoff Eagling for the update below.

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 26 February 2016

LLANDAFF SCHOOL FOR THE DEAF AND DUMB (1862-1906) was founded by Alexander Melville (1820-1891), who had begun his teaching career under Charles Baker at Doncaster. Melville, who was not deaf, was born in Carlisle, and Doreen Woodford says “extensive research has revealed nothing of his early life or family” (p.5). He was certainly at Doncaster School in 1846, before moving to London in 1849, where we are told, “he was mainly instrumental in originating and organising a Sunday service for the deaf, which he carried on for some time” (BDM, 1897, p.77, Woodford ibid.). Woodford gives a few details of his time in London where he worked for the ‘Red Lion Square Institution’, forerunner of the R.A.D.D. (now R.A.D.), helping people find work and holding signed services. Financial problems of the new institution probably forced Melville to return to Doncaster, but his friend Samuel Smith left Doncaster for London in 1854 to work for the revitalised institution, and Melville left and after a hiatus of five years he started working in Swansea School (ibid). Melville was the headmaster, but he clearly found it difficult to bend to the views of others, so he decided to found his own private school, which opened in 1862 near the cathedral (Woodford, p.6). After about three years, larger premises were required. “In passing in and out of Cardiff, Mr. Melville often cast a longing eye on a neglected little public-house on the borders of the Llandaff parish, which had been a flourishing hostelry in the days when telegraphs and railways were unknown” (BDM). The new premises, in Romilly Crescent, remained the home for the school until it closed.

LLANDAFF SCHOOL FOR THE DEAF AND DUMB (1862-1906) was founded by Alexander Melville (1820-1891), who had begun his teaching career under Charles Baker at Doncaster. Melville, who was not deaf, was born in Carlisle, and Doreen Woodford says “extensive research has revealed nothing of his early life or family” (p.5). He was certainly at Doncaster School in 1846, before moving to London in 1849, where we are told, “he was mainly instrumental in originating and organising a Sunday service for the deaf, which he carried on for some time” (BDM, 1897, p.77, Woodford ibid.). Woodford gives a few details of his time in London where he worked for the ‘Red Lion Square Institution’, forerunner of the R.A.D.D. (now R.A.D.), helping people find work and holding signed services. Financial problems of the new institution probably forced Melville to return to Doncaster, but his friend Samuel Smith left Doncaster for London in 1854 to work for the revitalised institution, and Melville left and after a hiatus of five years he started working in Swansea School (ibid). Melville was the headmaster, but he clearly found it difficult to bend to the views of others, so he decided to found his own private school, which opened in 1862 near the cathedral (Woodford, p.6). After about three years, larger premises were required. “In passing in and out of Cardiff, Mr. Melville often cast a longing eye on a neglected little public-house on the borders of the Llandaff parish, which had been a flourishing hostelry in the days when telegraphs and railways were unknown” (BDM). The new premises, in Romilly Crescent, remained the home for the school until it closed.

In 1865 Melville married Hannah Louisa Chappell (died 1885), a Deaf lady he had known for many years, who had attended the Old Kent Road Asylum. Woodford suggests that her money enabled to move to new premises (p.7).

Pupils were taught with a combined method, and annual reports show that they hammered home the religious education, as can be seen in the Report of the School for the Deaf and Dumb for 1883. John Clyne of the Bristol School interrogated pupils.

“What happened lately at Sunderland?” “A serious calamity. Nearly 200 children were killed from suffocation, and were crushed to death.” […]

“Where was there war lately?” was asked of H.L. [Harry Lowe] He wrote, “In Zululand and Egypt.” This led to the question, “Was Christ ever in Egypt?” The answer was, “Yes, Joseph and Mary took him there while Herod wanted to kill Him.” “How did Herod know about Christ?” “Wise men told him.” “How did wise men know?” “God told them.” […]

Altogether I was not prepared to find the pupils so well up as I found them. The removal of so many who were superior pupils last year induced the fear that the difference would be more marked than has proved the case. […] the only reason for regret is, that the support of the establishment is still nort on a scale permitting an adequate number of the necessitous Deaf and Dumb of South Wales to enjoy the benefits of the education which would so well meet their need” (p.15 & 18)

When Melville’s wife died he soon remarried, his second wife Elizabeth controlling Melville, then running the school after his death, but it did last for long after her death in 1904. Agar Russell was a teacher at the school from 1881-6, and he did not take to her, nor was he taken with the educational methods (Woodford p.20). From Russell we get a different view of her than appears in the article below, though it seems hinted.

LLANDAFF DEAF AND DUMB I SCHOOL. On Friday evening, in consequence of the death of Mrs. Melville, the hon. secretary, superintendent, and treasurer of the Llandaff Deaf and Dumb School, a meeting of the patrons, trustees, and subscribers of the institution was held, under the presidency of the Rector of Canton (the Rev. David Davies), for the purpose of considering the present position of the institution. In the course of a discussion it was stated that hitherto the institution had been entirely controlled and managed by Mrs. Melville and her late husband. It was reported that at present there were fifteen pupils in the school from various parts of the country, and, having regard to the very excellent work carried on in the institution in the past, the meeting felt that some definite scheme of administration and management should be formulated without delay. It was decided to appoint a sub-committee, consisting of the Rector of Canton, Mr. C. E. Dovey, Mr. J. Radley, Dr. Athol S. J. Pearse, Mr. P. J. Harries, and the Rev. A. G Russell, to take the matter in hand pending the summoning of a larger meeting, at which will be more fully gone into. Miss Barton, who had been staying with the late Mrs. Melville for some years, decided, with the assistance of Miss Simmons, to keep up the school until some definite arrangement was come to. At the close of the proceedings the Chairman proposed a resolution of sympathy at the death of Mrs. Melville, whom he described as a remarkable lady, with one of the strongest personalities that ever a lady possessed in Cardiff. The success of the Deaf and Dumb Institution was, undoubtedly, due to her wonderful personality. The proposition, seconded by the Rev. A. G. Russell, was supported by Mr. C. E. Dovey and Mr. J. Radley, and passed in silence. (Evening Express, 17th September, 1904)

Doreen Woodford, whose grandparents were at the school, gives a much fuller picture than I can offer here. Russell’s unpublished memoir is held in the library.

Appreciation. Deaf and Dumb Times, 1891, 3, 26-27 (illus)

Llandaff School for the Deaf and Dumb. British Deaf Monthly, 1897, 6, 77-78

Deaf and Dumb Magazine (Glasgow), 1879, 7, 155-56

Obituary. Quarterly Review of Deaf-Mute Education, 1891, 2, 347-48, 378

School reports, 1867-72, 1883, 1892-4, 1897

WOODFORD, D. A man and his school: the story of the Llandaff School for the Deaf and Dumb. Llandaff Society, 1996

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 19 February 2016

“It will soon be obvious to all rational minds that the deaf have been woefully miseducated, and their characters warped and stunted at their schools – terribly enough to justify the HOWL they emit.” (Ballin, 1930, p.12)

“It will soon be obvious to all rational minds that the deaf have been woefully miseducated, and their characters warped and stunted at their schools – terribly enough to justify the HOWL they emit.” (Ballin, 1930, p.12)

Albert Victor Ballin was born in New York in 1861, son of a German immigrant who worked as a lithographer. He lost his hearing through scarlet fever aged three. “Since then I have never heard voices, music or any sound – not even the firing of big guns. […] If the vibrations hang in the air, there remains in the atmosphere the silence of King Tut’s tomb for me.” (p.27) Being unaware of the manual alphabet, they used crude ‘home signs’. Ballin was convinced that through their ignorance “a blunder worse than a crime”, it atrophied his capability of learning to read and write (p.28). This anecdote he recalls deserves repeating in full.

When I was five or six, my brother, a hearing lad two years my senior, was accustomed to taking me with him to a baker’s shop, a block away. After many trips to the shop I was trusted to go alone to buy and bring home a loaf of bread. My mother wrote some words on a slip of paper, wrapped it over a nickel, andut both in my little fist. She admonished me in signs to be very careful to hold fast and not to lose the coin and to bring home a loaf. I carried out the errand so satisfactorily that she patted me on the head and commissioned me to repeat a like errand a few days later. This time she wrapped the written slip over five red pennies. I always had a sweet tooth for taffy, so I stopped on the way at my favorite candy store, filched one penny, and bought a wee handful of the confection.

Then I went into the bake-shop, chewing happily. I handed the slip and the remaining four pennies to the baker. He was aware of my deafuess, and he wasted no time to argue with me. He quietly scribbled something on another slip of paper and wrapped it with the bread. On my return home my mother asked me what I had done with the missing penny. I confessed my sin, and I was rewarded with a pretty stiff spanking, plus threats of a more severe punishment. I was profoundly astonished at her weird clairvoyance. How did she find me out? That set me to thinking deeply. I began dimly to suspect some connection between the baker’s slip and my spanking. On my next errand I tried an experiment: I filched a penny, bought the taffy and the bread, but this time I tore and threw away the baker’s nasty lime slip. When I arrived home with the loaf, I watched, with a throbbing heart, to see what mama would do. She only smiled kindly and patted my head. My ruse was a grand success-my guess was right. Thereafter I stole a penny on every like errand. How delicious was that taffy! (p.29-30)

The book begins,

Long loud and cantankerous is the howl raised by the deaf mute. It has to be if he wishes to be heard and listened to. He ought to keep it up incessantly until the wrongs inflicted on him will have been righted and done away with forever. (p. 17)

It is fascinating to read his description of his education. He faced great difficulties, and he points out that the 20% of pupils who were ‘semi-mute’ were the ‘show-pupils’ (p.41). He was angered by the failure to acknowledge the significance of sign language, and the prejudices of pure oralists (p.51). He deserves to be better known, if only for his book which was ahead of its time.

Ballin trained as an artist under Mr. H. Humphry Moore and attempted to make a living at that (BDT p.1, 1907). He went to Paris and Rome, studying under the Spanish painter Jose Villegas and in 1882 won a silver medal in Rome for a Venetian scene (ibid, p.1-2). He became friends with the Phillipino artist Juan Luna, sharing a studio with him (ibid). Back in America again, he painted portraits of the Rev. Thomas Gallaudet and Dr. Isaac Peet. He got involved in politics in support of the Democratic campaign in the 180s, which is how he met his wife (ibid p.3). He began then to specialise in miniatures.

Ballin trained as an artist under Mr. H. Humphry Moore and attempted to make a living at that (BDT p.1, 1907). He went to Paris and Rome, studying under the Spanish painter Jose Villegas and in 1882 won a silver medal in Rome for a Venetian scene (ibid, p.1-2). He became friends with the Phillipino artist Juan Luna, sharing a studio with him (ibid). Back in America again, he painted portraits of the Rev. Thomas Gallaudet and Dr. Isaac Peet. He got involved in politics in support of the Democratic campaign in the 180s, which is how he met his wife (ibid p.3). He began then to specialise in miniatures.

He later attempted to make it in films, having moved to California, appearing as an extra in many films , but “easily recognized in Silk Stockings [Silk Legs (?)] (Fox, 1927), The Man Who Laughs (Universal Artists, 1928)” etc. (Schuchman, p.27). He was a lead in His Busy Hour, (Heustis, 1926), a film with an all-deaf cast.

He died in California on November 2nd, 1932, not long after his book was published.

Below we see him with the silent film star, Laura La Plante. He was acquainted with a number of other ‘stars’, including Chaplin, Lon Chaney and Betty Compson, and he interviewed the oralist Alexander Graham Bell (Schuchman p.28).

Students whose colleges subscribe to Project Muse may be able to access the full text, which has also been reprinted by Gallaudet. Our copy of the book is signed, “Compliments of Howard L. Terry” (1877-1964), a Gallaudet alumnus who was a writer and became a Deaf activist when he moved to California (Clark, p.90-1).

Ballin, Albert, The Deaf Mute Howls, Grafton Publishing Company, Los Angeles, (1930)

Ballin, Albert, The Deaf Mute Howls, Grafton Publishing Company, Los Angeles, (1930)

Clark, John Lee (ed), Deaf American Poetry : an anthology, Gallaudet University Press, Washington (2009)

Notable Deaf of Today: Albert Victor Ballin, Artist. British Deaf Times, Vol. 4 no. 37 January 1907, p.1-4

Schuchman, John S., Hollywood Speaks : deafness and the film entertainment industry, University of Illinois Press, Chicago (1988)

http://www.silentera.com/PSFL/data/H/HisBusyHour1926.html

https://usdeafhistory.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/ballinalbert-bio-1.pdf

Silent Era : Progressive Silent Film List

His Busy Hour (1926) American B&W : Two reels Directed by [?] Albert Ballin? Cast: Albert Ballin [the hermit] Produced by James Spearing and Bertha Lincoln Heustis.

Post updated 15/12/16 with BDT article & picture.

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 5 February 2016

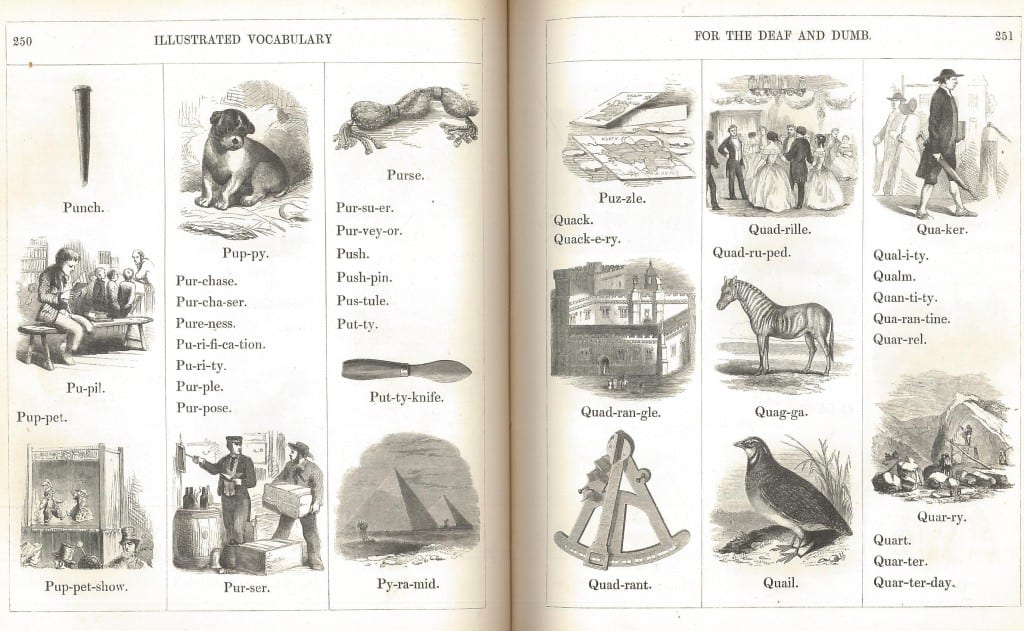

An Illustrated Vocabulary for the use of the Deaf and Dumb (1857), was written by Thomas James Watson, head of the Old Kent Road Asylum (and great nephew of Thomas Braidwood), and produced by the SPCK. That same year, Richard Elliott, who was later to became the headmaster, started to work as Watson’s assistant in the school. The engravings were “by Mr J.W. Whymper, from drawings by John and Frederick Gilbert, H. Weir, and others”. Watson says in his introduction that it was intended to cover words most common in usage, in Natural History, and in ‘Holy Scripture’. “Words which could not be thus illustrated are left for the teacher to explain by signs – the pantomimic language which must be adopted in the earlier stages of mute instruction.” (p.iii) He continues,

An Illustrated Vocabulary for the use of the Deaf and Dumb (1857), was written by Thomas James Watson, head of the Old Kent Road Asylum (and great nephew of Thomas Braidwood), and produced by the SPCK. That same year, Richard Elliott, who was later to became the headmaster, started to work as Watson’s assistant in the school. The engravings were “by Mr J.W. Whymper, from drawings by John and Frederick Gilbert, H. Weir, and others”. Watson says in his introduction that it was intended to cover words most common in usage, in Natural History, and in ‘Holy Scripture’. “Words which could not be thus illustrated are left for the teacher to explain by signs – the pantomimic language which must be adopted in the earlier stages of mute instruction.” (p.iii) He continues,

To those who are unacquainted with the peculiarity of the uneducated Deaf and Dumb, it may be right to state, that the Deaf can acquire a knowledge of language through the combined faculties of hearing and sight. This is a much slower process than learning a language through the combined faculties of hearing and sight. It should be borne in mind, that the Deaf can have no conception of the nature or use of words; whereas persons who hear commence to perceive the application of words long before they can use them or know their meaning. The Deaf must have the meaning of the word given to them at the time they learn it, or they will not be able to apply it: so that, in fact, they learn what they acquire of a language more completely than ordinary children. But, in consequence of their natural defect, the process of their education is naturally tedious, and a much longer time is required to enable them to use words as the expressions of their thoughts, and as the means of communication with their fellow-beings. (ibid, p. iii-iv)

The end of the book has a section devoted to trades, many now rare or dead, like a needlemaker, a gun manufacturer, and a coach-body maker. These were trades a boywho was deaf might hope to get an apprenticeship in.  If not they might end up in the ‘p’s on page 219 – as a pauper.

If not they might end up in the ‘p’s on page 219 – as a pauper.

Interestingly, while we have three copies, none of them look to have been well-thumbed. I wonder if, when Watson retired, the book quickly dropped out of use.

I love the Quagga here – Equus quagga quagga – now known to be a subspecies of the plains zebra, which was extinct within a generation.

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 29 January 2016

There is nothing spectacular or unusual to say about today’s subject. He seems to have lived a particularly ordinary life. Augustus William Argent was born on the 19th of December 1846 in Fetter Lane, Fleet Street. He became deaf aged two, through scarlet fever (Ephphatha 1898 and 1911 census). Aged nine (1856) Augustus went to the Old Kent Road School (Ephphatha 1898). His father Isaac was a printer compositor, and Augustus followed him into that trade when he left the Old Kent Road Asylum, being apprenticed to Messrs. Graham and Lowe. That firm went bankrupt so he finished the last four years of his apprenticeship at Spottiswoode and Co. printers, remaining there for a total of 53 years (Ephphatha 1917 p.496, Ephphatha 1898). During the latter part of his apprenticeship we are told that he found his English deficient,

so he resolved to devote his spare time to mastering the language with the aid of a dictionary. He often sat up half the night reading and studying the meaning of every word.” (Ephphatha 1898).

In his memoir Gilby says of him “Language excellent but no speech.” (p.146)

When he retired, he said, “My advice to the young men is, ‘study your trade and learn to do well.'” (Ephphathat 1917, p.497).

In 1871 he married a deaf lady, Catherine Oliva Broughton (1849-1922), and they had a large family (eight children according to the 1911 census), including two sons who became compositors, one of them serving in the Boer War and one wounded in the First World War (ibid p.497). In 1881 they were living at 4 Waite Street, Camberwell, and according to the 1911 census, when they were living at 26 Constance Road, East Dulwich, she had lost her hearing aged 3 (circa 1852/3).

Augustus died in 1917. In his obituary, Willian Raper said of him, “His influence for good was very great, and he will be much missed in London.” (p.497)

He was an ernest temperance worker, and was to be seen sometimes in connection theewith at the late Mr.J.P. Gloyn’s centres in North London. In former days he was a prominent figure at the debates and lectures at St. Saviour’s, Oxford Street, W., and the Rev.W. Raper has quite a collection of old syllabuses containing Mr. Argent’s name and subjects. He worked under the the Revs. S. smith, C. Rhind, and W. Raper, with latterly the Rev. F.W.G. Gilby as superintendent-chaplain.

Raper, William, The Late Mr. A.W. Argent, Ephphatha 1917 p.496-7

Raper, William, The Late Mr. A.W. Argent, Ephphatha 1917 p.496-7

Ephphatha (First Series) 1898, vol.3 p.

CENSUS

1851 Class: HO107; Piece: 1527; Folio: 203; Page: 41; GSU roll: 174757

1861 Class: RG 9; Piece: 220; Folio: 8; Page: 13; GSU roll: 542594

1871 Class: RG10; Piece: 426; Folio: 8; Page: 10; GSU roll: 824633

1881 Class: RG11; Piece: 698; Folio: 50; Page: 15; GSU roll: 1341163

1891 Class: RG12; Piece: 485; Folio: 45; Page: 27; GSU roll: 6095595

1901 Class: RG13; Piece: 517; Folio: 78; Page: 35

1911 Class: RG14; Piece: 2472

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 22 January 2016

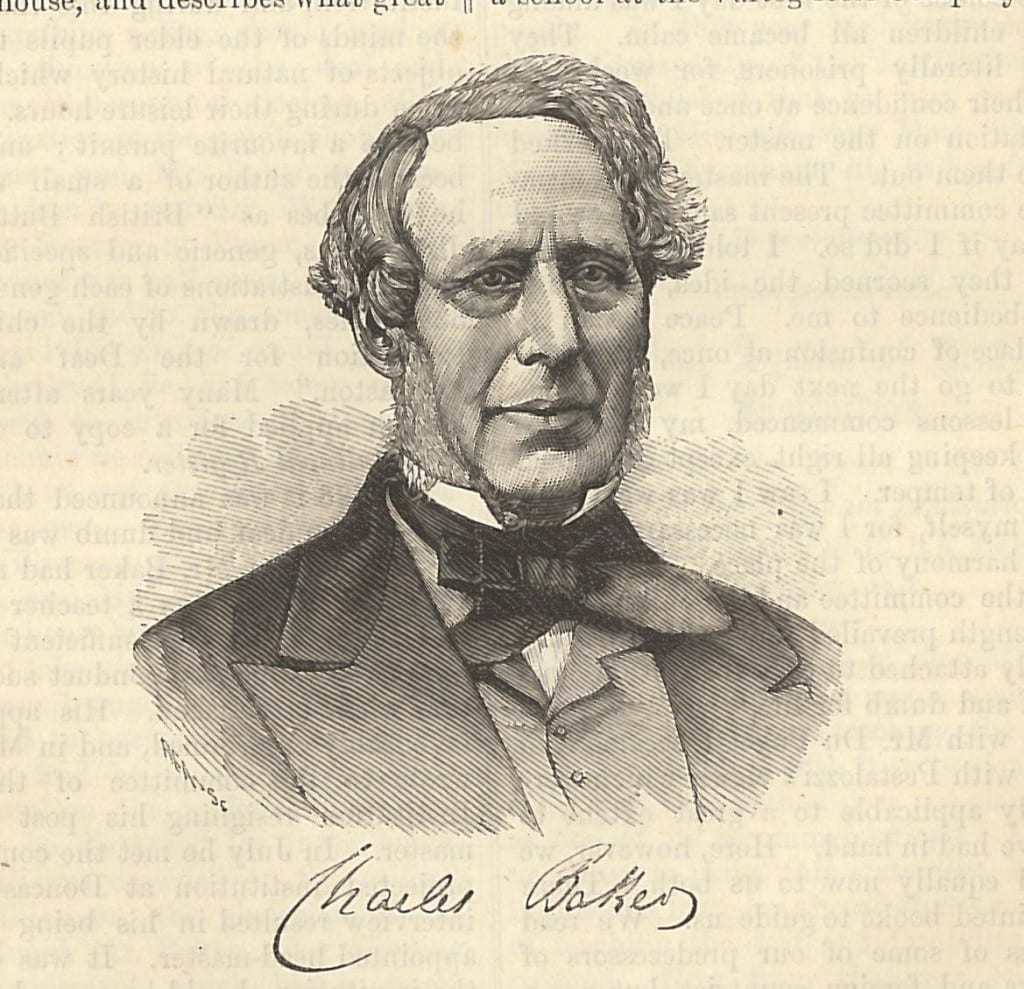

Charles Baker, (1803-74) was a teacher of the deaf, headmaster of the Yorkshire Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in Doncaster. The biographical sketch in A Magazine intended chiefly for the Deaf and Dumb, ran into three sections, which shows how highly he was regarded at the time (pp.8-11, 24-8, 38-9). The article tells us that Charles, born in Birmingham on the 31st of July, 1803, was the second of thirteen children.

He was but a youth when his attention was first attracted to the deaf and dumb. His father, while walking with him one day, directed his attention to a gentleman, and informed him that he had just come to Birmingham to establish a school for the deaf and dumb. This excited his curiosity, and his father promised to take him to an examination of the deaf and dumb children. He went to the examination, and was much pleased with the intelligence and acquirement’s of the children. They were under the care of Mr. Braidwood, a grandson of the Braidwood who was the first teacher of that name in Great Britain. (ibid, p.8)

He taught at the Deritend and Bordesley (now suburbs of Birmingham) Sunday School when only fourteen. In this way he became known to “most of the leading men of the neighbourhood” (p.8). In 1818 he took charge of the School when Braidwood had to go away, but Baker said,

He taught at the Deritend and Bordesley (now suburbs of Birmingham) Sunday School when only fourteen. In this way he became known to “most of the leading men of the neighbourhood” (p.8). In 1818 he took charge of the School when Braidwood had to go away, but Baker said,

not a book used in their instruction was to be found. All had been carefully locked up, as though the craft would have been in danger if a boy of fifteen had been allowed to penetrate into its mysteries. However, there were copy-books, drawing-books, pictures, and writing and drawing materials. Some hours were spent each day in improving work, and the rest in play, and long walks about the beautiful neighbourhood.

Some of the “gentlemen connected with the Institution wished to engage him permanently as an assistant, but Mr. Braidwood’s consent could not be obtained” (ibid). Aged seventeen Baker went to teach at Wednesbury, in the school established by the Quaker businessman Mr. Samuel Lloyd (of the banking family) remaining there for two years (ibid p.9). At that time he made the acquaintance of the Rev. William Jackson who had married the widow of a Captain White Benson of York. It was there that he met Edward White Beson, who became Charles’s friend and married his sister, Harriet Baker. Their son Edward became Archbishop of Canterbury. When Charles was twenty, he moved to Wales, running a school at the Vartag Iron Company’s Works in Pontypool, stay there until 1826 (ibid p.9).

Some of the “gentlemen connected with the Institution wished to engage him permanently as an assistant, but Mr. Braidwood’s consent could not be obtained” (ibid). Aged seventeen Baker went to teach at Wednesbury, in the school established by the Quaker businessman Mr. Samuel Lloyd (of the banking family) remaining there for two years (ibid p.9). At that time he made the acquaintance of the Rev. William Jackson who had married the widow of a Captain White Benson of York. It was there that he met Edward White Beson, who became Charles’s friend and married his sister, Harriet Baker. Their son Edward became Archbishop of Canterbury. When Charles was twenty, he moved to Wales, running a school at the Vartag Iron Company’s Works in Pontypool, stay there until 1826 (ibid p.9).

Back in Birmingham he was asked back to the Birmingham School. After Braidwood died, Louis du Puget, a pupil of the Italian teacher Pestalozzi became the headmaster. Unfortunately he struggled to control the pupils.

Mr. Du Puget was an intelligent man and a good teacher, but not specially qualified for the teaching of the deaf and dumb. I was called upon, and most urgently requested by Dr. De Leys and Dr. Alexander Blair, to go again and assist in the management of the institution; they represented the place as being in a state of utter disorganization and confusion, the lads running away at the rate of three or four a day, and the girls in rebellion, the matron disaffected like the children towards the master, and the assistant master, who had resided there for several years, had gone away. At first I positively and firmly declined any such engagement, but the picture they drew of the position of affairs, threatening the very existence of the institution, induced me at last to promise to pay a visit to the institution the next day.

In the course of the first day I was among them, the children all became calm. They had literally been prisoners for weeks. I obtained their confidence at once and without any imputation on the master. […] I saw I was weaving a net round myself, for I was necessary to the continued harmony of the place. The solicitations of the committee and the children and others at length prevailed so far that I became permanently attached to that institution, and to the deaf and dumb for life.

While with Mr. Du Puget I became well acquainted with Pestalozzi’s views, which were undoubtedly applicable to a great extent to the work in hand. Here, however, we had a field equally new to both of us. There were no printed books to guide us. We read the theories of some of our predecessors of ancient days and foreign countries, but not a scrap of practical information as to modes of procedure had been left behind by those who had previously occupied our position. Night after night we worked almost in the dark at courses of instruction in language, and day after day we taught during school-hours and discussed at other times different modes of conveying the knowledge of the English language to our pupils. I had now made up my mind that it was no ignoble office to walk in the steps of Dalgarno, Wallis, Braidwood, De l’Epee, Sicard, and others who had devoted their thoughts and their lives to raising the condition of those who, deprived of hearing, have never attained, or if once attained have lost, the power of speech. (ibid, p.9-10)

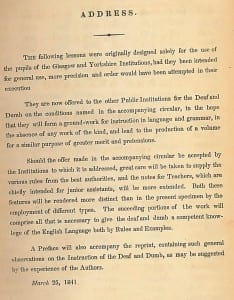

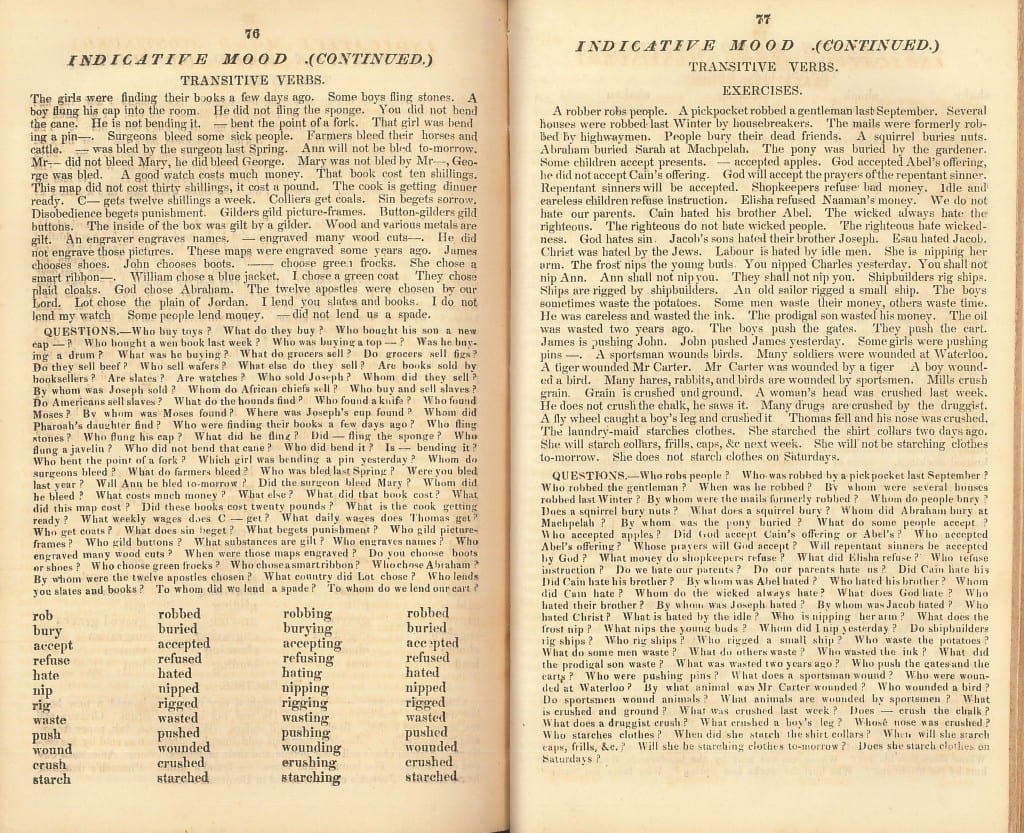

Our copy of the book he co-wrote with Duncan Anderson of the Glasgow Institution, published in 1841, was acquired by Charles Rhind in 1842, when he was teaching in Belfast. Rhind seems then to have made a practice of obtaining books on various educational methods. Above in the introduction we see that this book came with the offer of notes for teachers. The examples of sentences in the following picture are intriguing. Click the images for a larger size.

Baker resigned from his Birmingham post in 1829, moving to Doncaster to open the new school there. When the school was established, he turned his mind to producing educational material, and in 1831 published his first educational book, with many more to follow. He was a pioneer in producing this type. A list of his works can be seen here.

Baker resigned from his Birmingham post in 1829, moving to Doncaster to open the new school there. When the school was established, he turned his mind to producing educational material, and in 1831 published his first educational book, with many more to follow. He was a pioneer in producing this type. A list of his works can be seen here.

The private library of Charles Baker, is now in the archives of the Edward Miner Gallaudet Memorial Library, Gallaudet University, Washington, D.C.

Baker, Charles and Anderson, Duncan, A series of graduated lessons in language and grammar, for the instruction of the deaf and dumb. Doncaster, 1841.

Biography. Magazine intended chiefly for the Deaf and Dumb, 1876, 4, 8-11, 24-28, 38-39.

BOYCE, A.J. The Baker Collection. Deaf History Journal, 2000, 4 (2), 22-34.

Picture lessons for boys and girls translated from the French of Valade-Gabel by Charles Baker. No date. Historical Collection.

C. W. Sutton, ‘Baker, Charles (1803–1874)’, rev. M. C. Curthoys, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1109, accessed 22 Jan 2016]

We have more of Baker’s books.

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 15 January 2016

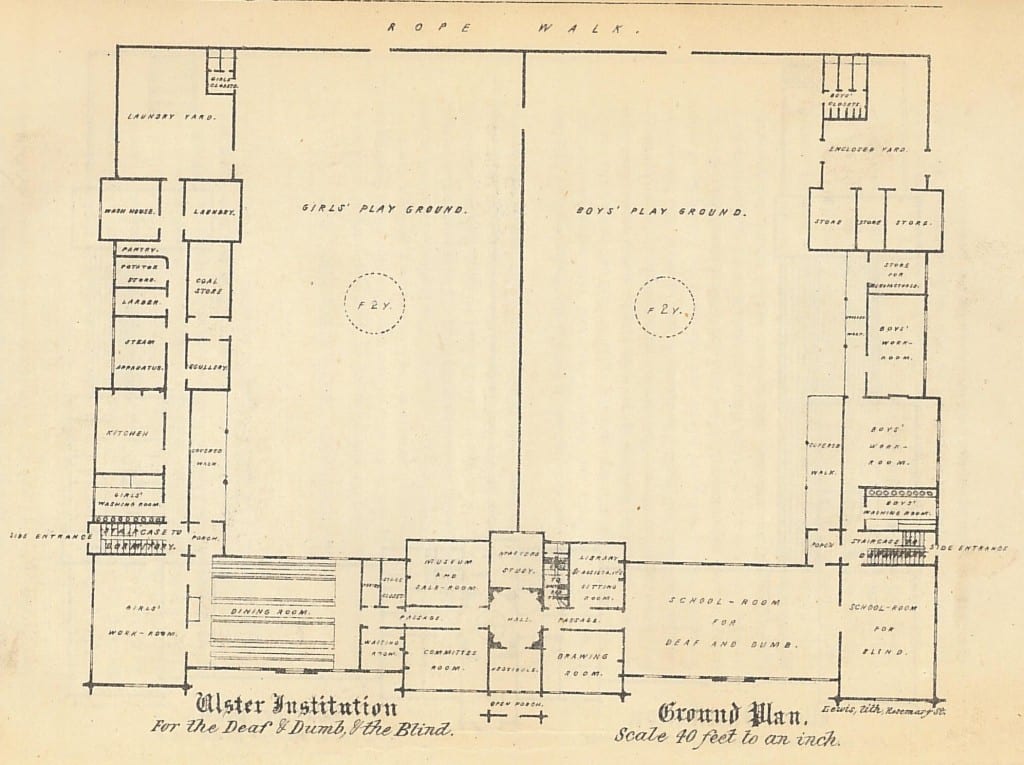

Formed from a society founded in April 1831 after a public lecture, the Ulster school began the following year in the retiring-room of an Independent Chapel in Donegall Street (Some information etc, p.9). It was initially a day school only. When the school moved to King Street in 1833, there were only eight pupils in attendance. A new teacher, Mr. Collier, was appointed in October 1834, and shortly after the first blind pupil was taken on. More money was required for a proper institution building, so in April 1835 a further public meeting resolved to raise the necessary funds, and as soon as February 1836 the new building, in College Street, was completed (ibid p.10). Within five years they had outgrown this building, and the foundation stone for a much grander establishment was laid on 31st August, 1843. Shortly after, an agreement was arrived at with the Claremont School in Dublin, that they would withdraw from Ulster (ibid, p.11).

Formed from a society founded in April 1831 after a public lecture, the Ulster school began the following year in the retiring-room of an Independent Chapel in Donegall Street (Some information etc, p.9). It was initially a day school only. When the school moved to King Street in 1833, there were only eight pupils in attendance. A new teacher, Mr. Collier, was appointed in October 1834, and shortly after the first blind pupil was taken on. More money was required for a proper institution building, so in April 1835 a further public meeting resolved to raise the necessary funds, and as soon as February 1836 the new building, in College Street, was completed (ibid p.10). Within five years they had outgrown this building, and the foundation stone for a much grander establishment was laid on 31st August, 1843. Shortly after, an agreement was arrived at with the Claremont School in Dublin, that they would withdraw from Ulster (ibid, p.11).

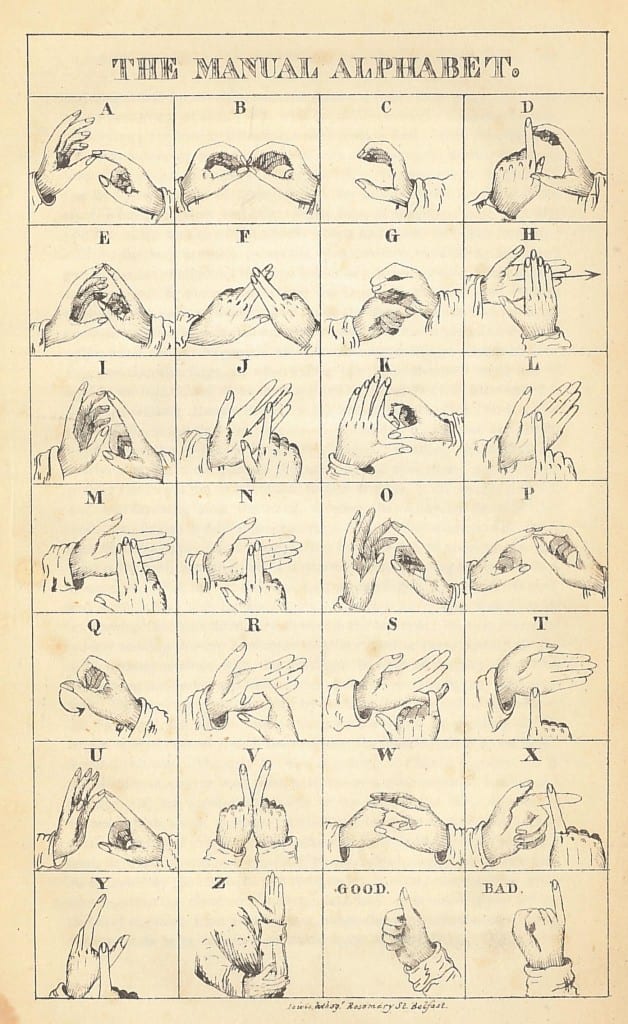

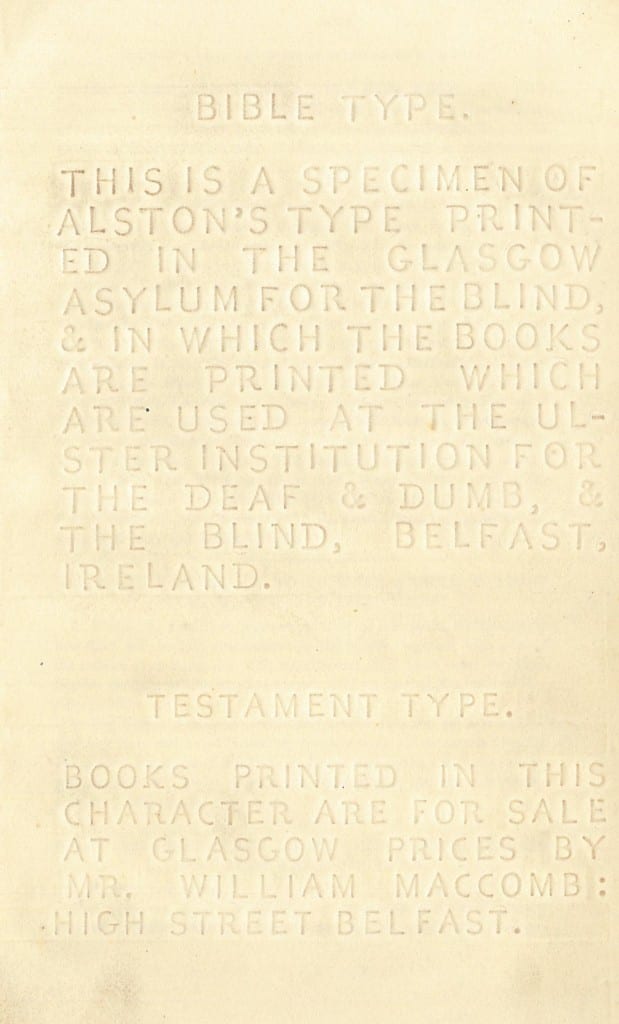

Below we have a picture of the Institution, a manual alphabet illustration, type used by the blind pupils, and the ground plan, all taken from Some information […] published in 1846.

The Ulster Society for Promoting the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, and the Blind. Some information respecting the origin, constitution, object & operations of the Ulster Society for Promoting the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, and the Blind; especially designed for the use of the Society’s auxiliaries. Belfast, the Society, 1846. (Our copy was owned by Charles Rhind).

The Ulster Society for Promoting the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, and the Blind. Some information respecting the origin, constitution, object & operations of the Ulster Society for Promoting the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, and the Blind; especially designed for the use of the Society’s auxiliaries. Belfast, the Society, 1846. (Our copy was owned by Charles Rhind).

Quarterly Review of Deaf-Mute Education, 1891, 2, 262-69, 289-95.