East London Mail Centre and E1 Delivery Office, 180–206 Whitechapel Road

By the Survey of London, on 11 November 2016

The large concrete building which dominates the corner of Whitechapel Road and Cavell Street represents the last expression of postal activity on an extensive site which was once the centre of the Post Office’s operations in the East End. Before its closure in 2012, the East London Mail Centre (formerly known as the Eastern District Post Office) processed mail for the entire ‘E’ postal district, an area covering over 50 square miles from Chingford to Poplar, and was the eastern terminus of the Post Office Railway. During its 130-year association with the Post Office, the site has seen successive building projects prompted by rising workloads, technological developments and changing patterns of consumption.

East London Mail Centre, view from Cavell Street in 2016 (© Survey of London, Derek Kendall).

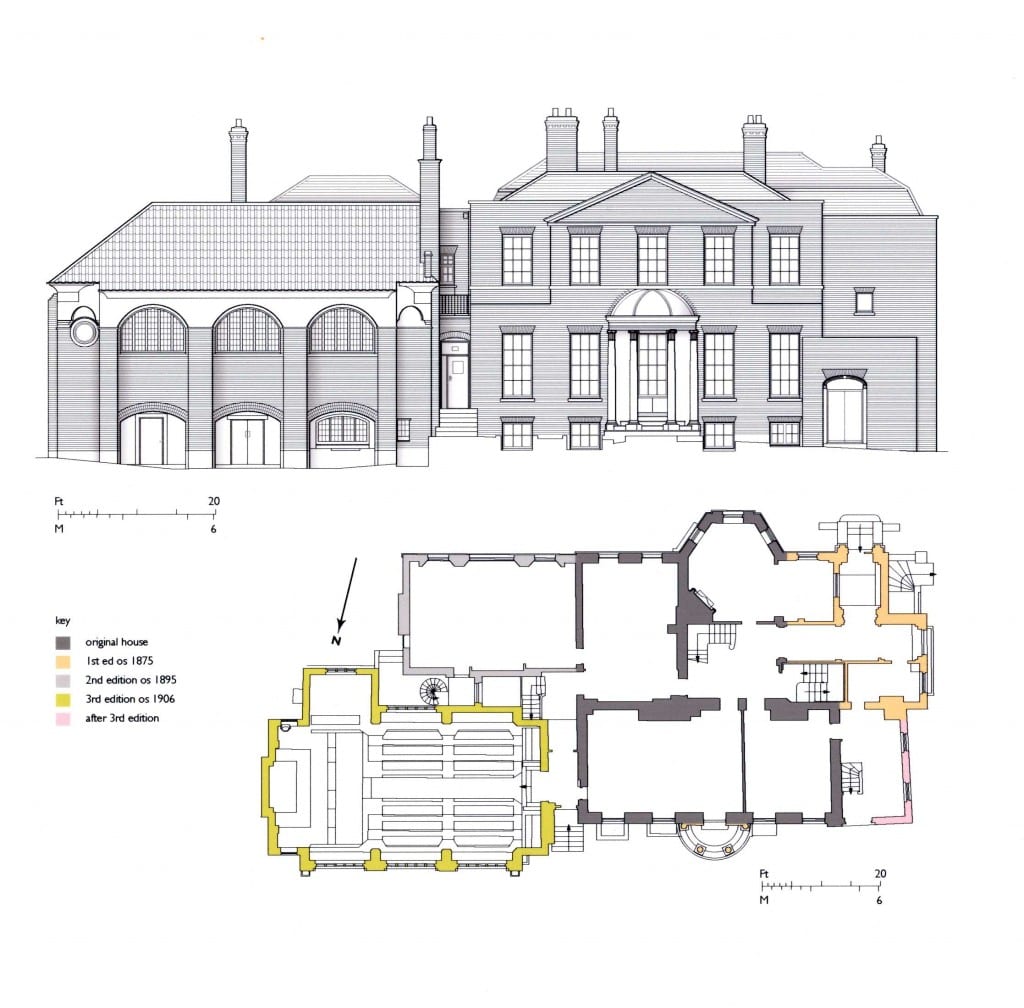

By the 1880s the Eastern District Office had outgrown its premises in Commercial Road and sought land for a chief office with room for expansion. It purchased a piece of former waste ground near the London Hospital, occupied by a paper-stainer’s shop and two cottages. With a 50ft frontage extending south from Whitechapel Road to Raven Row, the site was generous in size and its situation ideal. A new post office was built to designs by Henry Tanner of the Office of Works. It comprised a three-storey red-brick range with a public office fronting Whitechapel Road, and a single-storey sorting office at the rear. The main elevation of the public office was grand in character, with a central pedimented gable and round-arched windows on the third floor. In contrast, the sorting office presented a robust brick elevation to Cavell Street, with a plain staff entrance and large recessed windows.

Rapid growth in demand for postal services sparked plans to extend the building to relieve ‘cramped’ working conditions. By 1899 the number of letters processed at the Eastern District Office had increased twofold. Ground to the west of the building was acquired and a significant extension built to designs by Jasper Wager of the Office of Works, which nearly doubled the floor area. Further alterations followed with the construction of the Post Office Railway, or ‘Mail Rail’, to plans by William Slingo, engineer to the General Post Office, and Harley H. Dalrymple-Hay, consulting engineer. The underground electric railway was conceived in 1911 as a solution to the strain on London’s postal services caused by traffic congestion and a soaring volume of letters and parcels. It opened in 1927 to connect all of the capital’s major post offices, with its eastern terminus at Whitechapel. The line approached from Liverpool Street, following the route of Whitechapel Road before curving southwards to meet the station platform and terminating in a loop to the south of Raven Row. Although the railway was closed in 2003, the infrastructure survives and has attracted proposals for reuse.

Map of the Post Office Railway in 1937 (British Postal Museum and Archive catalogue)

East London Mail Centre, north elevation overlooking Whitechapel Road.

The introduction of mechanised postal sorting equipment in the 1930s led to new requirements for sorting offices and Whitechapel Road’s was probably considered unsuitable for modernisation. A scheme for redevelopment of the site seems to have been in place by 1956, when plans indicate that the adaptation of the former clothing factory on the east side of Cavell Street for post-office use was considered, most likely as an interim measure. The acquisition of Nos 180–188 Whitechapel Road and the adjacent builder’s works provided a substantial site with a frontage of over 200ft.

The earlier buildings were demolished and the present Modernist building constructed in two phases by 1970. The first phase comprised the eight-storey west block, which housed a ground-floor public post office with administrative offices above. It was followed by the adjoining four-storey sorting office, which extends along Cavell Street to Raven Row. The drab utilitarian exterior was the product of a short-lived initiative to standardise the design of post office buildings, in a new house style showcased in a 1960s exhibition produced by the architects’ department of the Ministry of Public Building and Works, headed by Eric Bedford. The main elevation facing Whitechapel Road is divided into eleven bays clad with prefabricated-concrete panels and horizontal bands of glazing. The structural frame of the building is exposed on the ground floor by four concrete columns flanking the van entrance to the sorting office. The widely publicised ‘modular system’ was contrived as a ‘common approach’ to building design to make post offices ‘instantly recognisable in any setting’.

Photograph of a model of the Eastern District Office (BPMA catalogue)

Van entrance to the former sorting office, flanked by open concrete shafts.

The interior of the sorting office was laid out for a mechanised workflow, which processed four million items each week. The ground floor functioned as a loading yard, with large entrances for postal vans opening onto Whitechapel Road and Raven Row. A warren of chutes and conveyors enabled the flow of letters, parcels and mail bags between stages in the sorting process. A chain conveyor brought inward mail bags from the yard to the sorting floors, to be processed by specialised machinery. The first, second and third floors of the sorting office comprised open-plan rooms with continuous steel-framed windows on each exterior wall to maximise light provision. Offices for inspectors were formed from light partitions. The Eastern District relied on over 2,000 postal staff working through the day and night, and a lounge, games room and bar were provided on the fourth floor.

Isometric plan of the basement, ground floor, first floor and mezzanine (BPMA catalogue)

Isometric plan of the second, third and fourth floors (BPMA catalogue)

The East London Mail Centre did not survive plans announced in 2000 to modernise London’s sorting system and, at the time of writing (2016), its former offices are occupied by tenants and only a modest delivery desk continues to operate. As the site has been earmarked for redevelopment by Tower Hamlets Council, the building is likely to be demolished.

The Survey of London has launched a participative website titled ‘Histories of Whitechapel’. Please visit at https://surveyoflondon.org.

Close

Close