Harley Street

By the Survey of London, on 13 October 2017

Harley Street has long been synonymous with the top echelon of the medical profession, a Harley Street consultant the apogee of the profession. This reputation was forged in the second half of the nineteenth century, and although it dimmed a little in the years after the Second World War, it enjoyed a resurgence in the late twentieth century with the growth of private health care.

General view of the west side of Harley Street looking south from New Cavendish Street. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Howard de Walden Estate and the Survey of London. © Historic England

The street itself has preserved its residential appearance, despite the fact that for the most part residence is now confined to upper-floor flats. It was first conceived in the early eighteenth century, but largely laid out and built up between the 1750s and 1780s. Although much Georgian fabric remains, there has been considerable rebuilding, particularly in the southern stretches of the street.

Detail of 1–5 Harley Street on the corner with Wigmore Street, designed by Robert J. Worley and built in 1896-9. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

From the beginning Harley Street was one of the more fashionable addresses hereabouts, with aristocracy, gentry, politicians, high-ranking clergymen, military and naval officers resident for the London season. Here too were the portraitist Allan Ramsay, and J. M. W. Turner before he decamped round the corner to Queen Anne Street. Increasingly in the early nineteenth century wealthy merchants took up residence. Many owed their wealth to slavery, from sugar plantations in the colonies and later from the huge sums paid out in compensation to plantation owners following the abolition of the slave trade. Others had grown rich through the East India Company, so many that Harley Street became as notable for its ‘nabobs’ as it became for its doctors. As late as 1841 Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine reckoned that ‘the claret is poor stuff, but Harley Street Madeira has passed into proverb, and nowhere are curries and mulligatawny given in equal style’.

This general view of 74 to 82 Harley Street gives a good impression of the street’s Georgian character, and perhaps a sense of that monotony so disliked by the Victorians. The houses date from the 1770s, with the usual later alterations of balconies, stuccoed ground storeys and raised upper floors. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

During the earlier decades of Victoria’s reign members of parliament and lawyers were prominent in Harley Street. The street so epitomised dull respectability that it was chosen by Charles Dickens as the home of Mr Merdle in Little Dorrit, first published in 1855–7. Disraeli too, in Tancred published in 1847, derided ‘your Gloucester Places, and Baker Streets, and Harley Streets, and Wimpole Streets, and all those flat, dull, spiritless streets, resembling each other like a large family of plain children’. Disraeli’s great political opponent Gladstone occupied 73 Harley Street from 1876–82. His arrival coincided with his campaign on the Eastern Question, arising from the massacre of Orthodox Christians in the Balkans. On a Sunday evening in 1878 a ‘jingo mob’ gathered outside his house, hurling stones and verbal abuse at his windows.

73 Harley Street. Gladstone lived in the house previously on this site, which would have resembled those on either side. The present No. 73 was rebuilt in 1904 to designs by W. Henry White for the ophthalmic surgeon Walter Hamilton Hylton Jessop. The blue plaque commemorates not only Gladstone’s residence from 1876–82 but also Sir Charles Lyell who lived there from 1846–75. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

By this time Marylebone had long been associated with medicine. Indeed, medicine arrived at the same time as the housing boom of the 1750s onwards. Most of the early evidence relates to institutions for treating the poor. Hospitals, like housing, gravitated to healthy suburban locations close to open fields and fresh air. When the Middlesex Hospital was built on Mortimer street in 1757 it was at the very edge of the expanding city, as was the parish workhouse in Paddington Street.

Entrance to No. 118. The Georgian house on this site was rebuilt in around 1909–10 to designs by F. M. Elgood with stone carvings by A. J. Thorpe. Together with its neighbours to the south, Nos 114 and 116, it was reconstructed behind the retained façade in 2005–9 as consulting suites and a pathology laboratory for the London Clinic by the architects Floyd Slaski Partnership. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Today, Marylebone generally, and Harley Street in particular, is most closely linked with front-rank medicine and private consultants. From the mid eighteenth century, proximity to London’s teaching hospitals became important for top medical men who held prestigious posts in them. Closeness to aristocratic patients was another major consideration. By the 1840s there were sufficient eminent physicians and surgeons in Cavendish Square and Queen Anne Street to act as a magnet for others. However, around this time those at the top of their profession were as likely to reside south of Oxford Street as north. The medical directory for 1854 shows an even distribution between Marylebone, Mayfair and Bloomsbury.

Detail of the door to No. 72. The size and number of doctor’s brass plates were strictly controlled by the Howard de Walden Estate, with regular checks against the Medical Directory to weed out interlopers. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Harley Street’s subsequent primacy is probably accounted for by its immediate proximity to Cavendish Square – the acme of fashionable Marylebone. Even by 1874, when Harley Street’s significance was already established, being close to the square still mattered. In that year Sir Alfred Baring Garrod, physician and gout specialist, moved from 84 Harley Street further south to No. 10 simply to be nearer to Cavendish Square. Twelve years later the surgeon Sir John Tweedy’s move in the opposite direction, from No. 24 to No. 100, was regarded by colleagues as committing professional suicide.

For most of its history, the southern end of Harley Street was the more fashionable address. Nos 6 to 10 (to the left) were built in 1825–7, probably by the architect Thomas Hardwick. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

As fashionable society ebbed away from Marylebone in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a similar shift of smart medical practice might have been expected, but that never happened. By then many patients of all classes were travelling to see doctors rather than the reverse. But the main reason seems to have been that once a distinct medical community had been established it was found to be enormously beneficial to those within it. This professional interaction is recalled in many memoirs of consultants, who placed great value on the ability to call on the advice or second opinion of a neighbour. In the twentieth century there was also an active policy on the part of the Howard de Walden Estate to preserve the Marylebone grid as a medical enclave.

Nos 51 (left) and 53 Harley Street. No. 51 was built in 1894 to designs by F. M. Elgood for the surgeon William Bruce Clarke on the site of the Turk’s Head pub. No. 53 was designed by Wills & Kaula and completed in 1914–15 as a home and practice for the surgeon and urologist Frank Seymour Kidd. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

The image of the Harley Street doctor relies much on the traditional kind of premises he inhabited. The standard London town house needed little alteration to turn it into a doctor’s house. Ground-floor front rooms became waiting rooms instead of dining rooms, with a consulting room either immediately behind or in the closet wing.

Nos 82 to 86 Harley Street. No. 84 in the centre was rebuilt in 1909 to designs by Claude W. Ferrier. The neurologist Walter Russell Brain had consulting rooms in No. 86 (on the left) in the 1960s. This retains its rich Georgian interior and was home to Russian ambassadors after 1780, including Count Simon Woronzow and Prince Andreyevich Lieven. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Originally, the doctor’s dependants occupied the remainder of the house above, but after families moved to the suburbs, houses might be converted or rebuilt as suites of consulting rooms for multiple medical occupation.

Nos 40 and 42 Harley Street show the contrasting architectural taste of the 1890s (No. 42 on the left, by C. H. Worley, brother of Robert J. Worley) and 1930s (No. 40, on the right, by Charles W. Clark, architect to the Metropolitan Railway Company). No. 40 was designed to resemble a private house but provided suites of consulting rooms behind a modish Art Deco entrance hall. No. 42 decked in Worley’s characteristic orange-pink terracotta was given Jacobean-style interior decor. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

In the later twentieth century many consultants gave up their private rooms for the better-equipped universities and hospitals. In their place came alternative practitioners and aesthetic therapists for whom the individual consulting rooms in elegant domestic settings provided a soothing backdrop. In the latest conversions encouraged by the Howard de Walden Estate there has been a policy of reconstruction to create purpose-built consulting suites over reinforced basements, allowing the latest diagnostic equipment to be installed behind retained facades, which preserve the historic character of the district.

Early twentieth century Birn Brothers postcard, poking fun at the Harley Street consultants and their patients. © H. Martin. Reproduced by permission of H. Martin

Daunt Books, 83 Marylebone High Street

By the Survey of London, on 22 September 2017

Daunt’s Bookshop, Marylebone High Street. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Howard de Walden Estate and the Survey of London. © Historic England

Daunt’s in Marylebone High Street is a favourite destination for book lovers. With its top-lit gallery, a remarkable Edwardian survival, it has one of the most distinguished interiors in the country. James Daunt took over the premises in 1989–90, initially specializing in travel books, and expanded into the next-door shop in 1999. But there had been a bookshop here since 1860. At that time it was in the hands of Francis Edwards. He had married in 1855 Sarah Anne Stockley whose father, Gilkes Stockley, was a bookseller with a shop in Great Quebec Street near Portman Square. After the marriage, Edwards took over Stockley’s business and five years later, with a growing family, moved to the High Street. He took the lease of what was then No. 83A. It became No. 83, as it is now, in 1927 (until then the present 83A was No. 83).

Detail of the gable of 83 Marylebone High Street photographed by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

The High Street as it developed during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was as mixed in shopping and business character as any London high street. In the early 1830s Thomas Smith, in his invaluable Topographical and Historical Account of St. Mary-le-Bone, summed up its humdrum character in a single sentence: ‘The houses have nothing to recommend them in point of architectural beauty, being plain brick buildings; and from their having been built at various periods are destitute of uniformity; they are, however, principally occupied by respectable tradesmen’.

Marylebone High Street, Daunt’s bookshop and on the right No. 83A, built around 1859. Photographed by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

There was some small-scale mid Victorian rebuilding of shops and public houses as leases expired, but nothing to alter radically the look of the street until the late nineteenth century when the Portland (later Howard de Walden) Estate began a systematic policy of complete rebuilding as the condition for renewing old leases. When Edwards moved to the High Street it was to a late eighteenth-century building, although the neighbouring premises to the north (the present 83A) had been rebuilt the year before.

The top-lit gallery at the back of 83 Marylebone High Street. Photographed by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

Originally specializing in theology, the shop expanded under the management of Francis’s son, also Francis, to become one of the country’s leading antiquarian bookshops. Theology gradually gave way to a new emphasis on travel, topography and maps. Business evidently thrived, as Edwards embarked on a no-expense-spared rebuilding in 1908. By that time the family was no longer living over the shop, having moved out to the London suburbs, first to Ruislip and then to Northwood. Edwards chose W. Henry White as his architect, among the best of a handful of architects regularly employed on rebuilding schemes on the estate around this time. At the same time White also designed No. 84, the adjoining property to the south, in a similar vein, and a few years earlier had designed Nos 70 and 71 (built in 1903–4).

Arched window at the end of the gallery at 83 Marylebone High Street. Photographed by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

Nos 83 and 84 are an unmatched pair in red brick with plentiful stone dressings topped off by shaped gables, in the commercial Queen Anne style favoured by the Estate. The date 1910 can be seen on a shield above the three arched windows lighting the attic of No. 83. The elegant shopfront with its central doorway flanked by large plate-glass display windows also has a side entrance providing access to the upper floors, all framed by pink granite piers and stall risers.

Shopfront of 83 Marylebone High Street. Photographed by Chris Redgrave. ©Historic England

Francis Edwards died in 1944, but the shop remained in the family until the late 1970s. The business was subsequently bought by Pharos Books in 1982 and the shop was briefly known as Read’s of Marylebone High Street. Francis Edwards still exists as an antiquarian bookseller’s, with premises at Hay-on-Wye and in Charing Cross Road.

Pediment over the entrance to Daunt Books, 83 Marylebone High Street. Photographed by Chris Redgrave © Historic England.

The recent series of Who Do You Think You Are, featuring Charles Dance noted that Dance’s ancestors the Futvoyes had an art shop at No. 83 High Street in the early nineteenth century, and the Howard de Walden archive shows that Charles Futvoye was granted a lease of No. 83 in 1819. This was, however, not on the site of the present No. 83. It may have been the present 83A, or a house further to the north, long since rebuilt.

University of Westminster, Marylebone Road campus

By the Survey of London, on 1 September 2017

South-east Marylebone is the home of the University of Westminster, founded in 1992. Though dispersed, its four main sites were inherited by the new university from the Regent Street Polytechnic via the Polytechnic of Central London (1970–92) and were purpose-built at various stages in that institution’s development. Whilst the Regent Street site goes back to the 1830s and the Little Titchfield Street site to the 1920s; the New Cavendish Street and Marylebone Road sites, planned simultaneously, are consequences of the great expansion of British higher education facilities in the 1960s, when the purposes of polytechnics were being reviewed and enlarged.

The science and engineering buildings in New Cavendish Street were farmed out to private architects in 1962, but the task of building the reformed polytechnic’s other two new faculties on the former Marylebone Workhouse or Luxborough Lodge site, was left to the LCC’s in-house staff. By the time this even grander project started on site, the LCC had become the Greater London Council and its education powers for central London had passed to the Inner London Education Authority. So the official credits for the buildings as erected in 1966–70 were as follows: designers, the GLC Architect’s Department, Education Section, with Michael Powell as chief education architect, Ron Ringshall as job architect and Frank Kinder and J. Buckrell as principal assistants; builders, Taylor Woodrow Ltd; client, the ILEA on behalf of Regent Street Polytechnic, from 1970 the Polytechnic of Central London.

Architectural model of proposed redevelopment of Marylebone Road campus (University of Westminster Archives, UWA/RSP/7/a/4/2)

The nearly four-acre site consisted of an extensive frontage to Marylebone Road, with a fair depth of land behind accessible on the east from Luxborough Street. It dropped down at the back, tapering slightly towards Paddington Street Gardens. The southernmost portion, furthest from the noisy main road, was reserved for the public housing that the LCC politicians had insisted must form part of the redevelopment. This was conceived as a single tower block (Luxborough Tower), standing directly behind a thinner second tower to its north designated as a student hall of residence. The educational buildings were divided by the architects into three, all set over a continuous concrete podium 3ft above Marylebone Road, allowing a deep basement at the back where ground levels were lower. The main road frontage was entirely taken up by a long, linear teaching building, reserved in the first place for the college of architecture and advanced building technology. At a central point the lower storeys of this monumental frontispiece opened up into a courtyard, backed by a T-shaped building dedicated to communal and service facilities of various kinds ranging from lecture theatres and a library to engineering construction halls underneath. The third element, the college of management, occupied a simple north–south block parallel to the western boundary, defined by the rear of flats in Chiltern Street. These latter blocks were linked by covered ways at first-floor level to the student hostel at the back, which comprised 178 study-bedrooms and 40 larger bed-sitting rooms for management students – many of whom were expected to be mature, short-course students on release from industry. Under the lee of the T-shaped block and facing Luxborough Street an extra single-storey building was slipped in, a local office for district surveyors.

The setting of these separate elements round paved open space, sturdily shielded from the main road, offered the Polytechnic a campus air it had not previously enjoyed. On the other hand the frontage itself struck an urban and triumphalist note, not rare in public-sector architecture of the 1960s. The concept was of a concrete megastructure, forceful enough to command attention on a major traffic artery, articulated by insistent horizontals for the accommodation against verticals for the circulation, bristling with expressed escape stairs at the two ends, and crowned by a hefty overhang along its full length. The priority given to the overhang, which straddles both sides of the front building, was symbolic, for here were located the architectural studios. The teaching of architecture had been to the fore throughout the pre-planning process. The section of these rooftop studios, taking up the fifth to seventh floors, therefore received the designers’ best attention; along each of the frontage’s four divisions between the circulation towers and stairs ran three interconnected levels, with spaces of differing length, width and height, and sundry provisions for side and top lighting. Unlike the New Cavendish Street spaces, they were neither double-glazed nor mechanically ventilated, and so were subject to road noise and pollution.

University of Westminster, Marylebone Road campus, 2014 (photograph by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London) © Historic England (DP 177601)

By the time of the opening in 1970 of 35 Marylebone Road, as the complex was first formally known, the Polytechnic of Central London had just come into being. So long had elapsed since the early enthusiasm with which it had been planned that it was received with some weariness, reflected in the equivocal reviews of the buildings. The thirteen-year gestation ought to have resulted in a ’singularly beautiful birth. In the event it could be said to have been multiple and unadorned.’ So wrote Alan Diprose, a senior lecturer in building technology at the Polytechnic, in a scathing appraisal for the Architects’ Journal. He found fault with many features from the disposition of the library and the canteens to the blatant separation of the educational buildings from the council housing by means of a ‘70 metre high air gap … the two towers present their backsides to each other in a permanently rude gesture of disgust’. [1]

University of Westminster student housing tower at the Marylebone Road campus (left) and Luxborough Tower, looking east, 2014 (photograph by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London) © Historic England (DP177602)

Marylebone Road had been first conceived as a monument to the integration of construction skills; the grandiose title ‘College of Architecture and Advanced Building Technology’, which survived till the opening, reflected that. But the removal of science and much of engineering from the project and the substitution of management studies undermined that technocratic purpose. The whole vision of a superschool in construction – a ‘National College of Architecture’ – was already fading when the LCC became the GLC in 1965, and was to vanish entirely as the public sector lost glamour. Certainly the facilities which the Regent Street Polytechnic’s School of Architecture inherited when it moved to Marylebone Road in 1970 were far superior to those it had enjoyed in Little Titchfield Street; it was probably the best equipped such school in Britain. But the final organization and remit of the college of architecture remained unsettled till the last moment, and left critics with a sense of fragmentation rather than the promised integration. Already it was being hinted at the time of the opening that polytechnic schools of architecture and construction had failed to differentiate themselves from their university counterparts, except by the lower pay of their staff.

Courtyard of the Marylebone Road campus, c. 1971 (University of Westminster Archives, UWA/PCL/7/a/4/2/27)

Since 1970 the site has seen both diversification and intensification of use. Architecture, construction and management are now among many topics taught at Marylebone Road under the University of Westminster, and the buildings have been several times altered and expanded to accommodate the various changes. The permeable front and paved court have disappeared, leaving very little of the site open to the elements. The most significant such changes were the infilling of the entrance void and erection of a canopy in 2002 by Dannatt, Johnson Architects, and their creation of the Hogg Lecture Theatre in the back block. This was followed in 2012 by a large-scale refurbishment by GM Rock Townsend, architects, which fully-roofed the open courtyard to create a new informal social learning space. Blighted by insensitive partitioning and subdivisions accumulated over the years, the open-plan layout of the architecture studios on the fourth and fifth floors was reinstated in 2015 by Jestico+Whiles, architects.

Architecture studios, 2015 (© Richard McDonald, Jestico+Whiles)

Architecture computer lab and lecture hall, 2015 (© Richard McDonald, Jestico+Whiles)

Reference

[1] Architect’s Journal, 2 June 1971, pp. 1245–64.

Western District Post Office, 35–50 Rathbone Place (demolished)

By the Survey of London, on 11 August 2017

This, the second of our postal posts, is a complement to the story of the East London Mail Centre published here on 11 November 2016 with its mention of the narrow-gauge Post Office Underground Railway or ‘Mail Rail’. Since then, in July 2017, a section of Mail Rail has been restored to use and opened to the public at the Postal Museum at Mount Pleasant (see www.postalmuseum.org). This railway was a mail-transport line that connected Whitechapel to Paddington. Tunnels at a shallow depth (averaging around 70ft) and 9ft in diameter were built by John Mowlem and Company in 1914–17, though the tracks were not laid and equipment fitted until 1924–7 for what opened as the world’s first driverless electric railway.

Another aspect of the line’s history relates to a site in south-east Marylebone, the area that is covered in the Survey of London’s forthcoming volumes 51 and 52, set for publication in late 2017. A site immediately above the mail-transport line in the West End, on the west side of Rathbone Place, suffered significant Second World War bomb damage. Despite the railway the Post Office faced growing problems with access and loading at its West End offices (Western Central District Office, New Oxford Street: Western District Office, Wimpole Street; and Western District Parcels Office, Bird Street). This was said after the war to pose ‘the worst postal accommodation problem in the country’.1 It led to a decision to replace the last two depots and their underground stations with a new Western District Office at Rathbone Place. The site was designated for compulsory acquisition to this end in the London County Council’s Development Plan of 1952, and passage of the Post Office Site and Railway Bill in 1954 enabled the purchase of 2.3 acres, in the event voluntary. With Sir William Halcrow & Partners as engineers the railway was expensively diverted from a diagonal south-east to north-west path across the site to take on an east–west line for a station with two platforms square to the intended building. The cut-and-cover underground works were carried out in 1956–9. Elbow room thus gained permitted a facility less like a Tube station than the line’s earlier stops. Designs for the building above were reworked in 1960 by Alan Dumble, a senior architect in the Ministry of Works. Its first, in the event only, eastern phase was largely up by 1963. The new Western District Office was opened on 3 August 1965 by the Postmaster General, Anthony Wedgwood (Tony) Benn.

Former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place, from the north east. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

On the long Rathbone Place frontage the building’s concrete frame was expressed in a 28-bay grid between Portland stone-faced stair towers. The fourth storey was set back leaving the structural frame as openwork. Along the pavement, mural artwork was intended but never made. A plan to extend westwards, also not seen through, meant that the utilitarian rear elevation was left starkly open to view from Newman Street behind a large parking yard. Here art did eventually arrive – the flank wall of 15 Newman Street facing the Post Office yard, and Oxford Street beyond, was the site of Banksy’s ‘One Nation Under CCTV’ mural of 2008.

Vans in the basement of the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

Inside the post office a ramp led to a basement with parking for vans above the railway station. When new this was among the most mechanized post offices in Europe, with chain conveyors in the upper-storey sorting halls and spiral chutes to despatch mail down to the railway. Its opening coincided with the introduction of post codes and the use of electromechanical sorting machines. The fourth floor housed a canteen and other facilities for staff who numbered more than a thousand. A reconfiguration in 1974–6 provided a bar, games room and lounge, and incorporated stained glass and war memorials from antecedent post offices. A small aedicular Ionic War Memorial of c.1920, transferred from the Wimpole Street office, faced Rathbone Place from 1981 to 2013.

Staircase in the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

Sorting floor in the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

Sorting floor in the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

Sorting floor in the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

Sorting floor in the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

The long disused games room of the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

The games room of the former Western District Post Office, Rathbone Place. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

The railway closed in 2003 by which time staff numbers had begun a steep decline justified by decreases in demand for the post. Remaining postal services in what had become the West End Delivery Centre relocated to Mount Pleasant in 2013. This shift had been long in the planning and in 2011 the Royal Mail Group with PLP Architecture had proposed redevelopment of the whole site as ‘Newman Place’, offices, shops and housing with a diagonal pedestrian throughway. Later that year Royal Mail sold the site to Great Portland Estates, retaining an interest through a profit-sharing agreement. A new scheme was prepared and granted planning permission in 2013. This enlarged project, designed by Make Architects (Graham Longman, lead architect), has led to Rathbone Square, two L-plan blocks enclosing a central open garden or courtyard landscaped by Gustafson Porter and rising six to eight storeys for offices to the south-east, 162 dwellings to the north-west, with shops, restaurants and bars. The post office was demolished in 2014 and the new buildings have gone up since. The dormant Mail Rail line has been retained.

1 – British Postal Museum and Archive, POST 20/23, GPO report, January 1954

Berners Hotel, the London Edition

By the Survey of London, on 21 July 2017

Berners Hotel, Marylebone, now the London Edition. Entrance. Photographed in 2013 by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

The Berners Hotel is a rare instance of continuity in the area around Berners and Newman Streets. Though the current building dates only from 1905–11, the hotel can be traced back to 1826. In that year the pair of houses at 6-7 Berners Street were converted from a bank into a hotel, involving the dismantling of a massive strong-room at the back constructed of iron and stone. The bank had been established in 1792 by the firm of De Vismes, Cuthbert, Marsh, Creed & Company. Later known as Marsh, Sibbald & Co., it failed notoriously when one of the partners, Henry Fauntleroy, was hanged for forgery in 1824.

Berners Hotel. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

No such notoriety was attached to the hotel. It was one of many, small family-run establishments in the vicinity of Oxford Street, where fashionable comers and goers mixed with longer-term residents. From the 1820s the private houses in Berners Street were increasingly being turned into lodging houses or shops. Pietro Rolandi’s Italian bookshop was one such at No. 20, a haven for literary and political exiles, which first opened in the same year as the hotel.

Berners Hotel entrance lobby. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

In 1880 the hotel’s then owner, Richard Kershaw, sold up to the Berners Hotel Company, which acquired building and fittings alike, barring a piano belonging to Miss Kershaw and an assortment of display cases of stuffed birds. The company lasted a decade, being sold on in 1890 through Thomas Ward, of the London Music Publishing Company, to Berners Hotel Ltd among whose subscribers journalists (Henry Sutherland Edwards and George Augustus Sala) and minor musicians were strong. The hotel was renovated, and shamelessly puffed by the new management for its association with Fauntleroy and its ‘interesting woodwork, carvings, painted ceilings, &c’. Appropriately, in 1895 Ward, its managing director, was charged with the Fauntleroy-like offence of forging bills of exchange to do with the supply of beer and spirits to the establishment.

Berners Hotel entrance lobby. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

Not long afterwards another hotel opened near by in Newman Street, the York Hotel. Its manager was Emmeline Lawrence, known as Mrs Mary Clark. A Welshwoman of considerable ambition, she oversaw the expansion of the York Hotel and soon became manager of the Berners as well. Backed by a fresh company, the Hotel York Ltd, she determined to rebuild the Berners Hotel on a much-enlarged site. Slater & Keith were commissioned to design the new building, which went up in stages. The first part completed was at the back, at 82–83 Newman Street and 73–75 Eastcastle Street, wrapping round the Blue Posts pub at the corner. The second, much larger western phase hit a snag when two Eastcastle Street houses, scheduled for demolition but still occupied, collapsed in 1908, killing eight men, all Austrian, German, Italian or Swiss employees of the hotel. The management also fought but lost a long legal battle with the LCC about fire doors or screens in the hotel corridors.

Berners Hotel restaurant interior, view towards north west. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

Once the rebuilding of the Berners Hotel had been completed in 1910, it was connected to the York Hotel by a subway under Eastcastle Street. The two hotels thus linked both had their main ground-floor public spaces facing west towards Berners Street, where spacious coffee rooms, lounges and main stairs were to be found. But they looked quite different. The York with its two corner tourelles belonged to the late Queen Anne manner affected by Slater in the 1890s, whereas the later and bigger block of the Berners, perhaps attributable to his partner Keith, is an altogether more pompous Edwardian production, neo-Georgian in style touched by Frenchness, with plenty of Portland stone and carving to set off the red brick, a pedimented entrance, and two storeys in the mansard roof. The lounge and coffee room were both double-height spaces, caked in opulent Edwardian plasterwork.

Berners Hotel restaurant interior, view towards the south. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

In 1912–13 Mary Clark tried to expand her hotel empire with an even larger scheme for the Princess’s Theatre site on Oxford Street, and in 1914–15 she ventured on a further new building at 74 Newman Street housing garages for her clients’ cars on two levels underneath five floors of open dormitories for maids. This landed her in financial trouble and she had to go. Under her successor, Henry L. Clark (no relation), the two hotels prospered. In the late 1920s hot and cold water, electric fires and phones were installed in every room; at this time the hotels claimed to be able to sleep 500–600 per night. The smaller York Hotel or Hotel York survived Government requisitioning in 1918 to acquire an extension designed by Slater & Moberly facing Newman Street (Nos 78–79) in 1932. But after it was requisitioned again during the Second World War it was not reopened, becoming a nurses’ home for the Middlesex Hospital in 1946, and then in 1997 a block of flats. The Hotel York Ltd maintained its independent management of the Berners Hotel till 1957.

Berners Hotel, view of main stair from north-west. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

In 1972 the hotel was under threat, but following the intercession of John Betjeman (‘I don’t know who the architect was but he was somebody pretty good’) it was listed and survived. A long period of closure ended in 2013 when the Berners Hotel reopened as the London Edition, fully restored at the behest of Ian Schrager (as at the Sandersons Hotel), here working with ISC Design Studio and Marriott International. The main spaces have been generously restored but, as the management is keen to insist, ‘The London EDITION is no period piece … It is a potpourri of styles that only a sure hand could pull off’. [1]

Plasterwork detail, Berners Hotel. Photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England

1.London Edition press release 2013

Maersk (formerly Beagle) House

By the Survey of London, on 30 June 2017

Beagle House opened in January 1974, constructed on a site long connected to the shipping and haulage industry located at the northern end of Leman Street, Whitechapel. Frustrated by difficulties in obtaining planning permission for previous designs, the architect Col. Richard Seifert had been engaged by developer Wharf Holdings to push through a successful outcome for the nine-story office block on account of his well-known fluency in the planning codes. Capitalising on London’s booming market for speculative office developments, Seifert and Partners had grown from twelve employees in 1955 to three hundred in 1969 and Colonel Seifert estimated that his practice was responsible for over 700 office blocks. He remembered of London ‘you only had to lay the first stone and the office was let. The demand was difficult to satisfy.’ [1] Yet while other Seifert buildings such as Centre Point and Space House remained controversially empty years after their opening, Beagle House’s immediate tenancy was sure. Overseas Containers Ltd (OCL) was made up of a consortium of four shipping companies, formed to take advantage of the new opportunities presented by containerisation in the mid-1960s. As the initial excitement associated with OCL’s establishment waned, the move to Beagle House was designed to endear employees to stay with the company. The Board considered that ‘provision of an optimum working environment for all levels of staff [is] the overriding objective.’ [2]

Maersk (formerly Beagle) House from Leman Street, looking south-west. Photographed for the Survey of London by Derek Kendall, December 2016 © Derek Kendall.

As headquarters for OCL, Beagle House was designed to accommodate 900 staff, with rooftop services concealed behind an extension of the angular faceted panels that enveloped its exterior. Some described the building’s unusual plan as lozenge shaped, others ship shaped. The project architect for Beagle House was Henry Grovners, who was also the lead architect on Corinthian House in Croydon. Despite assertions from Seifert’s staff that there was no ‘house-style’, repeated motifs such as angled pilotis, expressive facades and rhythmic concrete panelling are evident in Beagle House as well as in many of the firm’s designs from this period. Ideas and technical details were carried over from one building to the next along with engineers and other design team members.

Façade detail of Maersk (formerly Beagle) House. Photographed for the Survey of London by Derek Kendall, 2017 © Derek Kendall.

However, rather than utilise Seifert’s in-house team, OCL appointed their own interior designers, husband and wife consultancy Ward Associates. The Wards were favoured designers of passenger-ship interiors in the 1970s, proving themselves capable of considerable creativity in confined spaces. As a result of these ship interiors, Neville Ward was awarded the title of Royal Designer for Industry in 1971. The couple shared a London office with Wyndham Goodden, Professor of Textiles at the Royal College of Art, who designed the Chairman’s office at Beagle House.

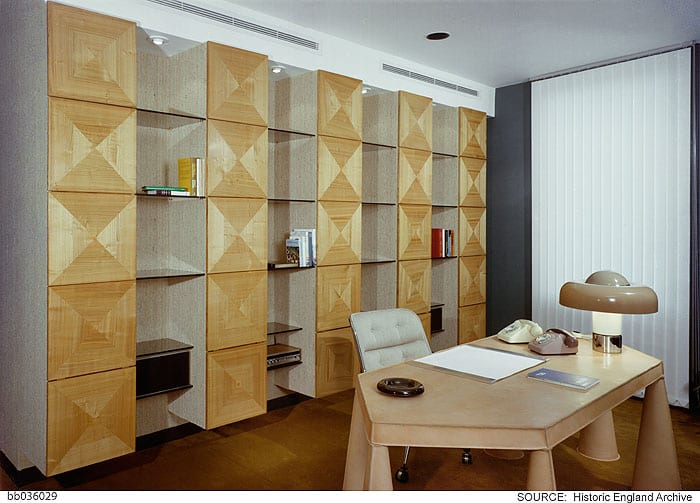

Chairman’s office designed by Wyndham Goodden. Photographed by Millar & Harris c.1974 © Historic England Archive

The building’s peculiar shape made provision of individual offices difficult, only a handful were designed, those clinging to the outer corners of the building. The open-plan interior was at first regarded as a six-month experiment in part, to ease anxiety from middle-level managers about the shift away from traditional layouts.

Ward Associates’ design for a typical open-plan office floor. Photographed by Millar & Harris c.1974 © Historic England Archive

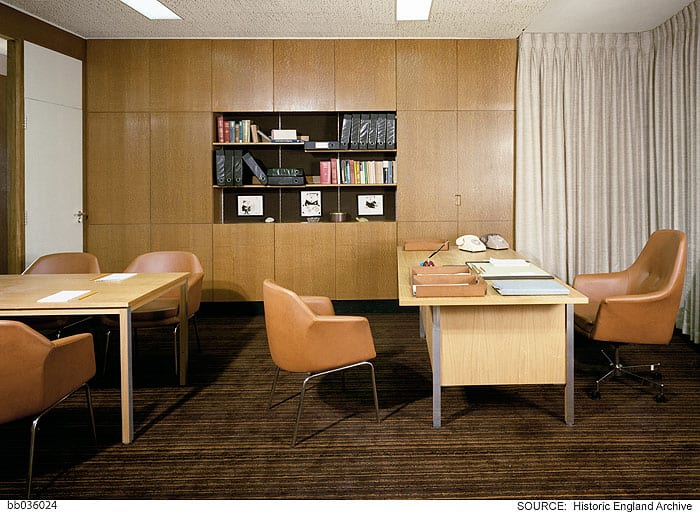

The top floor however was exclusively dedicated to upper-level management and company directors, each of whom was afforded the privileges of a separate office illuminated by plastic-domed roof lights and access to a serviced dining room reserved for their use.

Bar area for directors on the eight floor. Photographed by Millar & Harris c.1974 © Historic England Archive

Deep storage units divided each pair of offices leaving the open-plan central space to be occupied by secretaries.

Typical director’s office on the eighth floor. Photographed by Millar & Harris c.1974 © Historic England Archive

Addressing the concerns of managers on the lower floors who were uneasy about the loss of visual and acoustic privacy, Ward Associates carefully fashioned smaller enclosures using screens, planting and storage cabinets.

Storage cabinets and plants defined spaces within the open-plan layouts. Photographed by Millar & Harris c.1974 © Historic England Archive

Outside Beagle was skeletal and grey, while the interior was decorated in trendy hues of brown, orange and blue, each floor differentiated by a unique colour scheme. Floor-to-ceiling length curtains lined exterior walls and defined meeting spaces. There were coffee areas, a lounge, snack bar and the licensed subsidised canteen, while conference rooms were fitted with well-stocked bars, all intended to provide OCL workers with a palpable sense of home comfort.

Typical communal lounge area on open-plan floors. Photographed by Millar & Harris c.1974 © Historic England Archive

As computers and machines increasingly invaded the office environment, the interior-design press claimed that the general introduction of plants to interiors compensated for ‘the ever increasing emergence of soulless concrete edifices all too common today.’ They noted that ‘where a plant will survive so an office-worker’. The entrance hall was graced with a wall-mounted model ship and an interior fish pond. [3]

At this time interior designers were increasingly engaged in office designs that prioritised the comfort of workers and new mechanisms for climate control also worked to humanise working environments. Reflecting the forward-looking spirit of OCL, the new Beagle House claimed its own technological innovations in this respect. Writing in 1975, Interior Design regarded it as ‘London’s first privately developed Integrated Environmental Design (IED) office building…without a doubt, one of the most advanced buildings in the country’. [4] Suspended ceilings throughout Beagle House provided air-conditioning to all spaces powered by a roof-top plant. A resident engineer, responsible for the system’s ongoing maintenance, was allocated a first-floor flat in the building.

Following a number of corporate take-overs, Beagle House was renamed Maersk House in 2005. Standing aloof on pedestrianised Braham Street (since 2012 known as Braham Park), Seifert’s building faces imminent demolition in March 2017. ‘One Braham’, a glassy eighteen-storey office block with commercial units to the ground floor, was scheduled for completion in 2018 but Brexit has reportedly caused American developers, Starwood, to re-assess their involvement in the scheme, leaving Maersk House to languish in uncertainty.

If you would like to read more about the history of this site, or submit a personal memory of Maersk House, please access the Survey of London, Whitechapel, found here.

[1] BL, National Life Stories Collection: Architects’ Lives, Richard Seifert, 1996

[2] Caird Library and Archive, PON/1/3/10

[3] Interior Design, Jan 1975, p. 33, p. 36

[4] Ibid.

Gwynne House, Turner Street

By the Survey of London, on 9 June 2017

Gwynne House stands at the north-west corner of the Turner Street and Newark Street crossing in bold contrast to its contemporary neo-Georgian neighbour, the Good Samaritan public house. This block of flats was built in 1937–8 to designs by H. Victor Kerr, the architect of a number of interwar buildings in east London, including Commerce and Industry House in Middlesex Street (demolished), 67–75 and 101 New Road, 9–17 Turner Street and 47 Turner Street (demolished). While there is no known professional association between Kerr and the London Hospital, his designs repeatedly found favour on its Whitechapel estate. Kerr practised as an architect during the interlude in his military career between the world wars, in which he ascended to the rank of Major (Hon. Lt. Col.). Of his surviving works in Whitechapel, Gwynne House is the most assertive expression of the Modernist style. This five-storey block has a sleek white-painted façade with a curved staircase tower and a rhythmic succession of slender balconies with rounded edges. Gwynne House bears a resemblance to Wells Coates’s Isokon Building, which set a precedent in style, configuration, and the provision of ‘minimum’ flats intended for professionals.

Gwynne House and the Good Samaritan Public House from the north-east in 2016. Gwynne House was built in 1937–8 to designs by H. Victor Kerr. © Derek Kendall

Gwynne House replaced five early nineteenth-century terraced houses at 75–83 Turner Street and 23a Newark Street on the London Hospital Estate. By the 1930s this piece of ground had been earmarked for future hospital expansion. Despite initial reluctance to part with the site, the hospital agreed an 80-year lease with Lloyd Rakusen & Co. of Leeds in 1935. After their plans to build a biscuit factory were rejected by the LCC, Rakusen & Co.’s interest in the lease was transferred to a developer for a block of flats. Construction was by Moore & Wood, working as general contractors in association with specialized subcontractors. The reinforced concrete frame was enveloped by smooth external walls filled with cork insulation, and capped with a flat timber roof coated with asphalt. At its completion in 1938, Gwynne House provided twenty modern flats that were designed to attract ‘students, social workers and professional people in east London’. An additional rooftop flat was allocated to a caretaker. Each floor was divided into four small flats built to a standardised rectangular plan with a hallway, two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchenette and a bathroom. The elegant ‘tower feature’ encased an electric lift and a staircase, lit and ventilated by angular slits in the exterior wall. It also concealed a rubbish chute, a telephone kiosk, a switch room, and service ducts that communicated with a basement boiler room. [1]

Gwynne House from the south-east in 2016. © Derek Kendall

Gwynne House was quickly identified by the hospital as a convenient base for medical practitioners, nurses and students, though rents were judged to be ‘somewhat high’. [2] One of its first tenants was a young (Sir) John Ellis, who was later appointed physician to the London Hospital and Dean of the Medical College. Other prominent residents included Edith Ramsay MBE, a local social campaigner, and the nurse educationalist Dr Sheila Collins OBE. By the 1980s Gwynne House had been acquired for the hospital as rented accommodation for staff from all departments. Barts and the London Charity sold the block to a private developer in 2011. The exterior has seen minimal alterations, aside from the replacement of the original Crittall windows and the recent insertion of jaunty porthole doors. The original metal fence at the front of the block survives, characterised by sinuous lines echoing the projection of the tower. A narrow rear garden shelters a sycamore tree, a lime tree, and an ‘ancient’ mulberry tree. [3]

Gwynne House in 2016. © Derek Kendall

Do you have any memories of Gwynne House? The Survey of London has launched a collaborative website titled ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ and welcomes contributions. Please visit at https://surveyoflondon.org.

References

- The Builder (19 May 1939), p. 948.

- Royal London Hospital Archives (RLHA), RLHLH/A/5/64, p. 209.

- The Gentle Author, ‘The Whitechapel Mulberry’, Spitalfields Life, 30 March 2015 (online: http://spitalfieldslife.com/2015/04/30/the-whitechapel-mulberry).

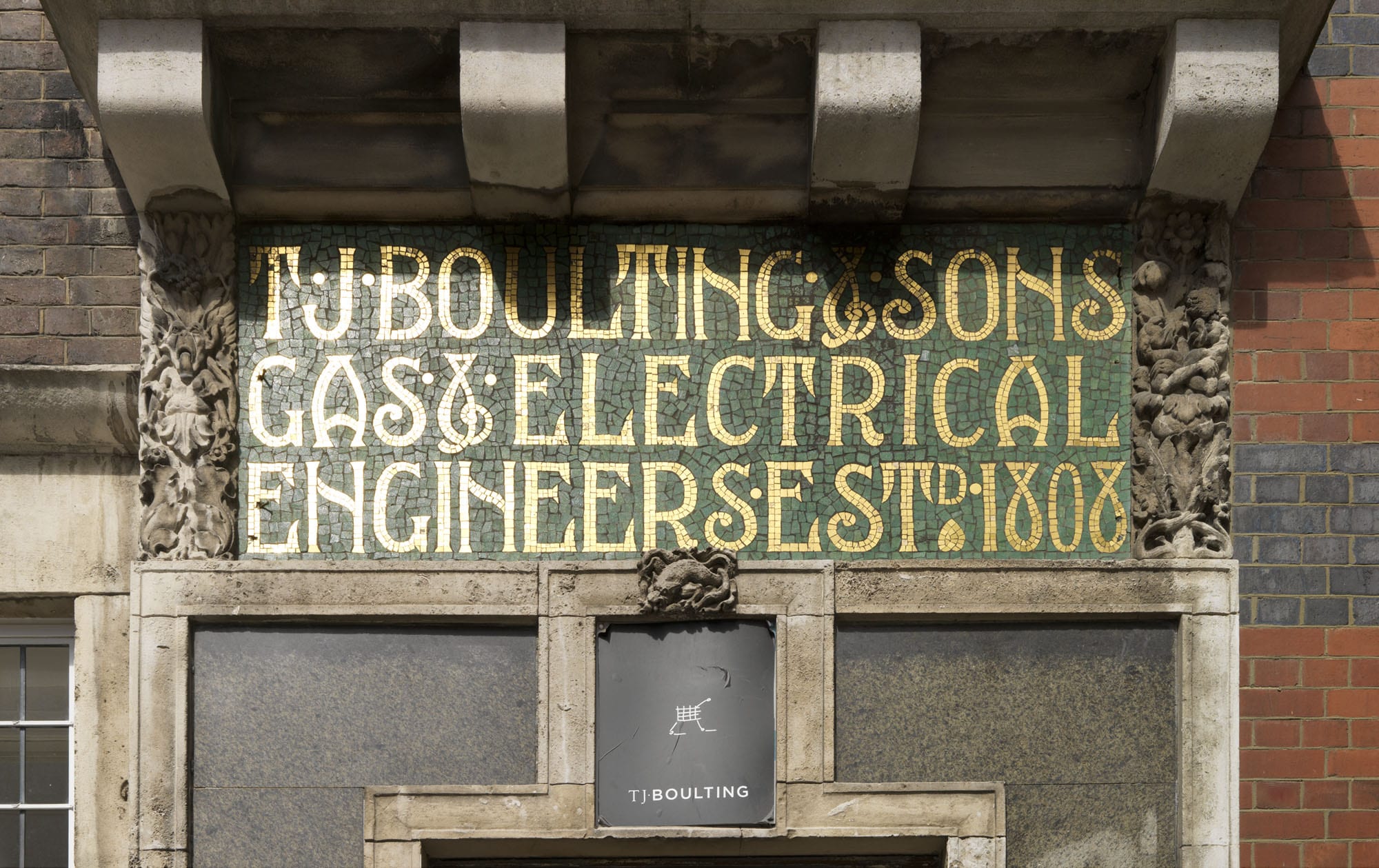

Boulting & Sons

By the Survey of London, on 19 May 2017

At the corner of Riding House Street and Candover Street stands one of South East Marylebone’s architectural gems: a group of flats designed for T. J. Boulting & Sons. John Boulting & Son, furnishing ironmongers, were established perhaps as early as 1808 in two nearby houses. This is the date that is proudly displayed on the building, picked out in gold mosaic tiles along with the company name.

Detail of 59-61 Riding House Street, Marylebone, Greater London. View from south. Taken for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Successive John Boultings died in 1863 and 1873, and a partnership dissolution between a third John and Thomas John Boulting was announced in 1879. Thereafter the firm was known as T. J. Boulting (& Sons).

59-61 Riding House Street, Marylebone, Greater London. View from south west. Taken for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Among these sons was Percy Boulting, born about 1876 and seemingly architect-trained, to whose youthful aspirations the present buildings may well have been due. The firm had done well enough for members of the family, at first the father and then Percy’s brothers, to branch out into small property dealings on the Howard de Walden estate from the late 1890s. Naturally they took a special interest in rebuilding around their works. Their first venture appears to have been 40 Foley Street, a five-storey block of flats directly behind the Boultings’ address, built by John Anley in 1898. Its designers were then described as Clark & Hutchinson with Percy A. Boulting, in other words H. Fuller Clark and C. E. Hutchinson, two architects aged about 28 who had met in the office of Rowland Plumbe, plus the even younger Boulting. Later No. 40 was ascribed to Clark alone, and it is to him that the flamboyance of the Boultings’ cluster is usually credited. Clark’s masterpiece is the recasting of the Black Friar pub in the City; otherwise his work is little known, though he claimed to have a substantial practice.

Flats built for Boultings at 40 Foley Street, designed by H. Fuller Clark, perhaps with H. E. Hutchinson and Percy A. Boulting. Taken for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Architecturally, No. 40 is an up-to-date but not eccentric performance which breaks into roughcast at second-floor level and terminates in two shaped gables. The plan follows the standard late Victorian arrangement in this quarter of two flats per floor, originally with a sanitary excrescence at the back in the form of a central stack of bays shared between two flats. Clark & Hutchinson promptly followed up in 1899 with a second block of flats opposite, Belmont House, 5–6 Candover Street, built this time by A. A. Webber. Here a similar plan is fronted in a weightier, fussier idiom, with a great belt of purple brickwork enveloping the first floor and a dab of Art Nouveau lettering.

Tower House, Candover Street. H. Fuller Clark and Percy Boulting, 1903-4. Taken for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

Tower House, York House and Oakley House, encompassing the Boultings’ former premises and the Sir Isaac Newton pub on the corner, followed on in 1903–4. This time the architects were described as Fuller Clark and Percy Boulting, without Hutchinson: the builders were Smith & Co. of Mount Street. Again these are essentially five-storey flats, though the backs go one storey higher; here too were originally bare sanitary stacks of bay windows. The fronts are the reverse of bare. Among the tricks set to work are brickwork bands of startling hues, bay projections both canted and square, a bristling roofline and three separate fancily lettered mosaic panels advertising the Boultings firm and its wares (‘gas and electrical engineers’; ‘sanitary and hot water engineers’; ‘appliance and stove manufactory’).

Detail of 59-61 Riding House Street, Marylebone, Greater London. View from south. Taken for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave. © Historic England

Colour was an evident preoccupation; originally three different cements were used, while the window joinery was all white apart from the bay windows, finished in stained oak. Despite the hint of Voysey about these elevations, they are entirely individual and indeed this building too was attributed to Clark alone when it was republished. The Boultings firm survived at 59 Riding House Street up until the 1960s. In 1978 the freehold of all their flats passed to the Community Housing Association, which employed Pollard, Thomas & Edwards, architects, to update them over the subsequent decade. Their changes included enlarging the sanitary bays at the back to form more generous kitchens.

Detail of 59-61 Riding House Street, Marylebone, Greater London. View from south. Taken for the Survey of London, by Lucy Millsom-Watkins © Historic England

71–73 Great Portland Street

By the Survey of London, on 28 April 2017

71-73 Great Portland Street, Joseph Emberton, architect, 1937. Photographed for the Survey of London by Chris Redgrave © Historic England

This building is a little known work by Joseph Emberton, showrooms of 1937 that would have been more boldly Modernist but for compromises that arose from the fact that the freehold of this entire street block was held by the Crown.

The site’s leaseholder from 1920 was Julius Turner (born Tanchan), who lived at 58 Portland Place and was a major figure in Great Portland Street’s motor trade through his control of Thorns. Turner stutteringly converted two shops for motor showrooms, first dubbed Crown Motors. In 1927 he asked the Crown Commissioners for a building lease at 71–77 Great Portland Street, wanting to build a ‘magnificent Motor Showroom’. He was rebuffed. Trouble had been caused by his parking and washing of cars, ‘Mr Turner (who is a naturalized Polish Jew) is not a particularly desirable tenant’. A second approach in 1929 also failed, but a more modest proposal for refurbishment of Nos 71–73 for Thorns gained approval in 1931. Turner then fell ill, suffering what was called a nervous breakdown in 1933. He returned to the fray in 1934, submitting new plans for rebuilding Nos 71–73 as motor showrooms below workrooms and offices. His architect now was Emberton, and the scheme was bold.

H. Meadows, the Commissioners’ architect, commented that ‘The proposed design conforms to present day architectural ideas of simplicity and utility. It is in contrast with its surroundings and for this reason is somewhat incongruous. The flat surfaces of the façade to the upper storeys in one plane rests apparently on the glass of the shop fronts of the ground floor and this has the effect of making the building appear to be lacking in adequate support. This is particularly emphasised on the angle of the building which is shown as a solid mass of walling unsupported by a curved plate-glass window.’ Told that the Crown could not object much more than to ask that ‘they adopt small letters instead of the monsters’, Meadows persevered in shriller terms: ‘the design violates the canons of good architectural composition by failing to satisfy the eye that the structure is self-supporting and therefore structurally sound … [it is] lacking in the element of apparent truthfulness, which is the indispensable quality of all good architecture. The proposals are of a revolutionary character architecturally and it is difficult to foresee what the reaction of the public is likely to be.’

The project, which proposed a dark vitrolite cladding, like that of Fleet Street’s Daily Express building, anticipated Emberton’s designs for Simpsons Piccadilly by a year. Emberton was ready to compromise when the delays were deplored by Turner in May 1935 at which point he, with his brother Joshua Philip Turner and Harold Gershom Vickers, was fined £1,010 for under-declaring the value of four imported cars and thereby defrauding Customs of £453. The Crown Lands Advisory Committee, which included Raymond Unwin and Frank Pick, made no objections to Emberton’s design other than to a proposed seventh storey and to the vitrolite cladding, suggesting stone or reconstructed stone instead. Turner, who had relaunched as the Lansdown Trust, was given new leases in 1936 but his desire for a reduction in rent caused further delay. Meadows urged Portland stone cladding, but Emberton pointed out that Great Portland Street was ‘mostly a brick street’ and suggested yellow brick, with the shopfront to be clad in the Empire Stone Company’s artificial Portland stone. The showroom and workroom building went up in 1937, with Dorman Long & Co. steelwork, Hunziker bricks (new to the UK), and John Knox (Bristol) Ltd as builders.

Motor showroom use was short-lived and the building stood empty after the war. Numerous and miscellaneous occupants since have come mainly from the garment trades, but have also included artificial-flower makers and, in the early 1970s, Hermes Computing Services Ltd’s punched-card service bureau. The ground floor has been reshaped and the building has lately been occupied by Motel, a fashion label.

(all quotes are from The National Archives, CRES35/2962)

‘Portland House’: Robert Adam’s unexecuted designs for the Duke of Portland’s London residence

By the Survey of London, on 7 April 2017

The Adam brothers’ celebrated street improvements at Mansfield Street and Portland Place, carried out from the 1760s on the Marylebone estate of the Dukes of Portland, are among the many significant buildings covered by the Survey of London’s forthcoming volumes on South-East Marylebone. Less well-known, however, is the detached mansion that Robert Adam designed around 1770–2 as a new London residence for the 3rd Duke, to stand on a large site on New Cavendish Street, looking down Mansfield Street. Though it was never built, its story can be pieced together from designs in the collection of Adam office drawings at Sir John Soane’s Museum – the principal resource today for anyone wishing to study the work of the Adam brothers.

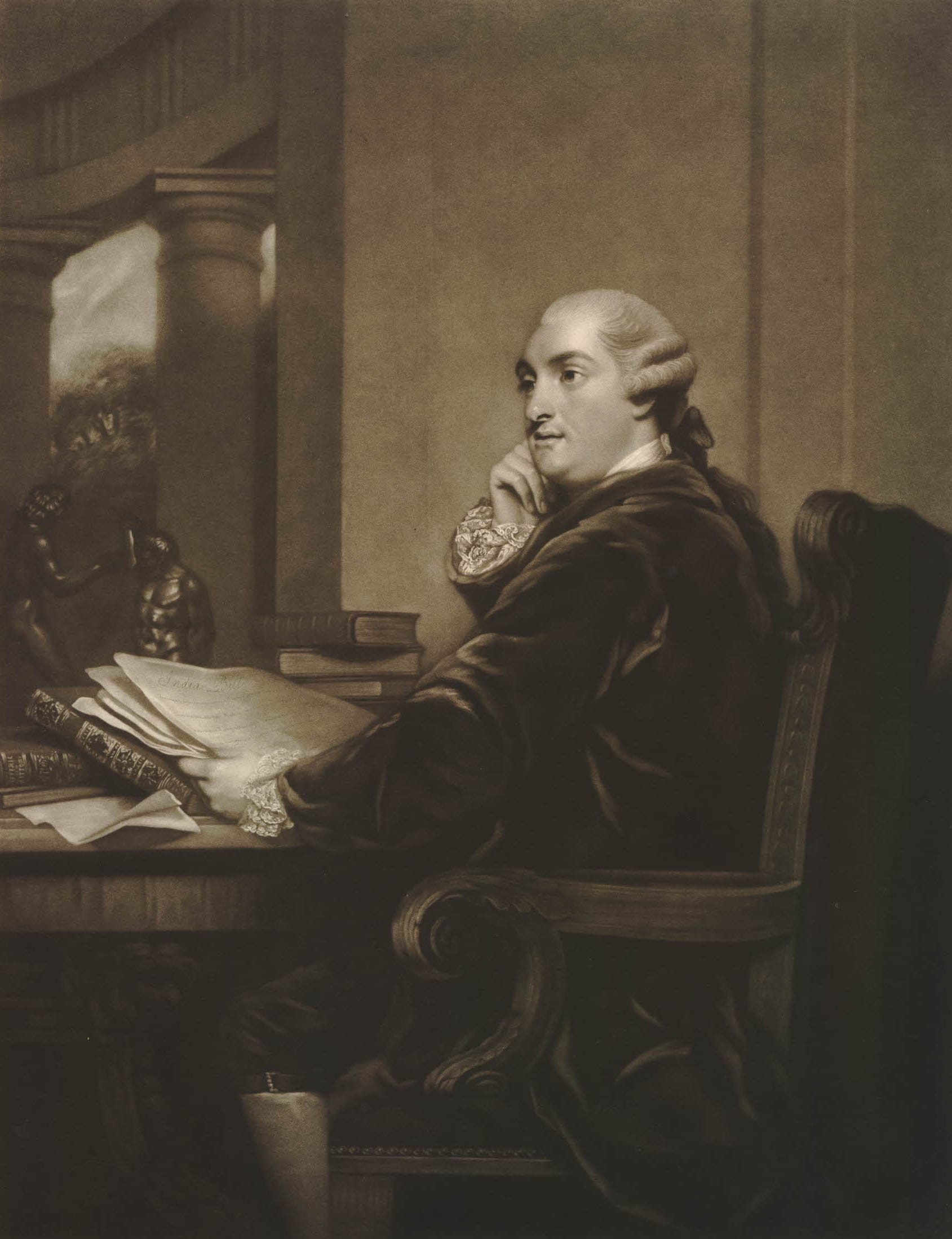

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland. An engraving of 1785 after Sir Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of the Duke. British Museum, Prints & Drawings Dept (museum no. 1902,1011.3545) © Trustees of the British Museum

William Henry Cavendish Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland (1738–1809), had recently married Lady Dorothy Cavendish, daughter of the 4th Duke of Devonshire, and was already embarked upon a career as a statesman that would see him appointed 1st Lord of the Treasury (the equivalent of today’s prime minister) on two occasions, in 1783 and 1807–9. But although he had succeeded to his father’s title in 1762, the 3rd Duke did not immediately inherit all his estates. By the terms of his father’s and grandmother’s wills, the Duke’s mother, Lady Margaret Cavendish-Harley Bentinck, the Dowager Duchess (1715–85), retained a life interest in the family’s lucrative Cavendish lands, and she also held on to her husband’s house in Whitehall – leaving her son short of funds and without a London residence. The situation was exacerbated by strained relations between the two. They argued over country seats, in the end engineering a ‘house swap’ (she favoured Bulstrode in Buckinghamshire, he preferred Welbeck, Nottinghamshire), and failed to see eye to eye on politics as well as family finances. The Duke was a Rockingham Whig, intent on curbing what he perceived to be an increase in royal powers under George III; she numbered the king and queen among her friends, and was especially close to John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, the royal favourite and prime minister in 1762–3, a man whom her son vehemently distrusted. The Duke complained to anyone who would listen that he was required to pay rent for a London house when he should have had access to the ducal residence in Whitehall. And so a new, Adam-designed townhouse at the head of Mansfield Street would suit his intended station as a leading politician and also act as a focus for his fast-improving Marylebone estate.

Portrait busts of William Bentinck, 2nd Duke of Portland, at centre, his wife Lady Margaret Cavendish-Harley at left, and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu at right, in ovals, with coats of arms below, allegorical objects between, curtains at left and above, in ornamental frame. From a drawing by Vertue after a painting by Zincke, 1739. British Museum, Prints & Drawings Dept (museum no. 1849,1031.70), © Trustees of the British Museum

In its size and scale the house that Adam designed, intended to be known as Portland House, was more like a country pile than a townhouse. In this and in certain elements of its internal planning it shared similarities with Lansdowne House, Adam’s first big private London commission, designed initially for Lord Bute but finished after his fall from favour in 1763 for his rival, another future prime minister, William Petty Fitzmaurice (1737–1805), 2nd Earl of Shelburne, later Marquess of Lansdowne.

Adam’s designs for Portland House were for a rectangular, two-storey block set within extensive grounds, with a garden to the rear and an entrance courtyard in front. The house itself would have been a fairly standard neo-Palladian affair, with seven central bays recessed behind projecting three-bay end wings. The entrance front was marked by a central portico with columns of what look like Adam’s favourite ‘Spalatro’ order – an invention of his own, based on a late-Roman capital he had seen in the Peristyle of the Emperor Diocletian’s Palace at Spalato on the Dalmatian coast (now Split, Croatia).

‘Principal Front of a House for His Grace the Duke of Portland’. Adam office elevation of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/2. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

Portland House was to have had a lower ground floor given over mostly to servants’ rooms and storage, but with a gentleman’s library in a bowed room at the rear, and a bedchamber for the Duke and ‘Book room’ alongside. The principal state rooms were placed centrally on the floor above, with dressing rooms for the Duke and Duchess to either side. These connected with the little single-storey bays shown in shadow at each side of the mansion in the elevation, where there were to be powdering and retiring rooms, privies and water closets. There would have been further rooms on the first floor and in an attic within the hipped roof.

One of a pair of Adam office plans shows a proposed design for the house’s lower ground floor, with a rectangular courtyard in front, lined with coach-houses and stables on one side, kitchens, sculleries and more service buildings on the other. This plan matches the elevation, and shows how the portico served as a porte-cochère, with a curved ramp for coaches leading up to the main entrance. Also, in this plan an entrance screen wall and gateway is set quite a way back from the road, with more stabling and coach-houses in front.

‘Plan of the Ground Story of a House for His Grace the Duke of Portland’. Adam office design of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/4. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

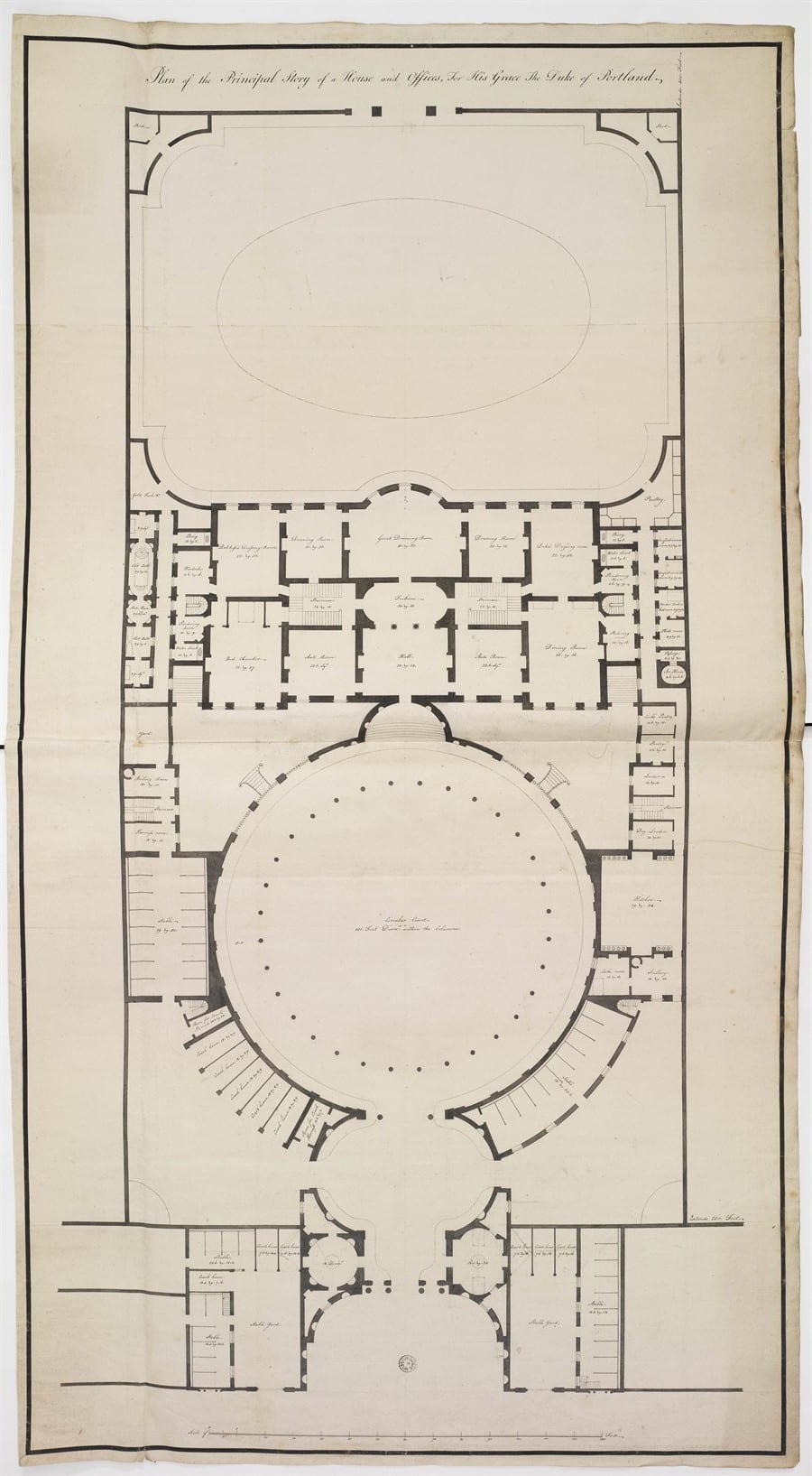

A first-floor plan offers an alternative arrangement, for a far more dramatic circular courtyard, surrounded by a roofed and colonnaded walkway. An accompanying section shows how this colonnade connected directly to the house, dispensing with the portico. This arrangement required further alterations to the design of the house, with windows at a higher level on the piano nobile, to allow light to enter the main rooms above the courtyard structure. Apparently this was the design chosen by the Duke.

‘Plan of the Principal Story of a House and Offices, For His Grace The Duke of Portland’. Adam office design of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/5. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

‘Section through The Gateway, Circular Court and Body of the House, For His Grace The Duke of Portland, Fronting Mansfield Street’. Adam office design of c. 1770–2. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/3. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

The Adams had been experimenting with colonnaded courtyards in house designs since the 1750s. Although their prime inspiration was always Italy, and in particular ancient Rome, there is a heavy debt to French plan-types, particularly Parisian hôtels, in their mansion schemes of the early 1760s. An unexecuted house of c.1764, intended for Lord Shelburne near Hyde Park Corner, was set behind a large front court, as was another design of the same date for a house for Lord Holland at The Albany, Piccadilly. Also, an early Adam brothers’ plan of around 1767 for the house they built for General Robert Clerk at the south end of Mansfield Street, facing Duchess Street, had the lower part of the house arranged in a curve and fronted by a semicircle of columns forming a carriage-way, in a similar manner to Portland House.

‘Gateway for Portland House’, Adam office design of c. 1770–2. This worked-up office version, with doors in the centre of the curved linking walls rather than windows, probably matches the rectangular courtyard plan for the house as shown in the ground-floor plan reproduced above. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 29/6. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

Other surviving drawings include an office elevation of a screen wall and gateway to stand on New Cavendish Street in front of the courtyard, in the form of a triumphal arch, closing the vista up Mansfield Street. A second version, in pen and pencil, apparently in Robert Adam’s own hand, has detailed measurements added to it, in preparation for drawing up estimates.

Design for a gateway for Portland House. This rendition in pen and pencil, in Robert Adam’s own hand, has had measurements added to help with working out an estimated cost, as mentioned in Robert Adam’s letter of February 1772 to the Duke, quoted above. Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 51/98. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum

As the Duke was both short of funds and overindulgent in his spending, a house on such a scale was evidently beyond his means. Unfortunately, the scheme also coincided with a reversal in the Adam family’s own fortunes, brought on by their attempts to develop the Adelphi and Portland Place at the same time. The Portland House project was still in hand in February 1772, when Robert Adam wrote to the Duke with a price for the ‘great gate’, porter’s lodges and some of the circular walls, and he sounded hopeful of further progress:

as Your Grace was so good as say, you would do every thing that should be necessary, to finish the end of the street, towards Your Grace’s House. I have therefore got an Estimate made of the great gate & porter’s lodges, with the circular walls that form the Entrance, & now take the liberty to send it enclosed, that Your Grace may consider it & if approved of, it will be of great Service, both to your Grace’s estate & to us, to be allowed to proceed with it this Season. [1]

But within a year the project had been dropped and the Duke was happy to let part of the site to the builder–developer John White for houses on the east side of Harley Street. The ground fronting New Cavendish Street was then leased by the Duke and the Adams to the architect-builder John Johnson, who erected the present Nos 61–63 there in 1775–6 (these will be the subject of a future blog post).

For a time around 1773–4 the Adams seem to have considered re-siting their ‘hotel’ for the Duke of Portland to the west side of Portland Place, where they had been planning at least two other very large aristocratic houses, for the Dukes of Kerry and Findlater, but this plan also failed to materialize, and the Duke of Portland when in London continued to live mostly at Burlington House, courtesy of the Duke of Devonshire. In 1807, when he was made 1st Lord of the Treasury for the second time, the Duke moved to 10 Downing Street, which was then as now the official residence of the 1st Lord of the Treasury (not the prime minister, though in modern times the same person has usually occupied both posts).

The Adams must have remained on reasonably friendly terms with the Duke, as they were allowed to continue to work on Portland Place, even though its completion was delayed until the 1790s by unfavourable economic conditions and the Adam brothers’ own financial problems; by then both Robert and James Adam were dead. Their cause may have been aided by the Duke’s friendship with their nephew, the Rt Hon William Adam of Blair Adam, the son of Robert and James’s older brother John Adam. A lawyer and advocate by training, and later a judge, he was one of the 3rd Duke’s great allies in the Whig party when it came to boosting party morale and raising funds in preparations for the general election of 1790.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks are due to Dr Frances Sands, Curator of Drawings at Sir John Soane’s Museum, for supplying the images of the Adam designs for the Duke of Portland’s house; these are reproduced here by courtesy of the Trustees of the Soane Museum. The catalogue entries for these drawings in the Adam office collection at the Soane can be found by following this link. A discussion of the designs also features in Fran’s book Robert Adam’s London, published to accompany the exhibition of that name recently held at the museum. See here for further details.

Reference

1. University of Nottingham, MSS and Special Collections, PwF 35

Close

Close