A Colour A Day: Week 52

By Ruth Siddall, on 21 March 2021

A Colour A Day: Week 52. 15-21 March 2021

Jo Volley writes…

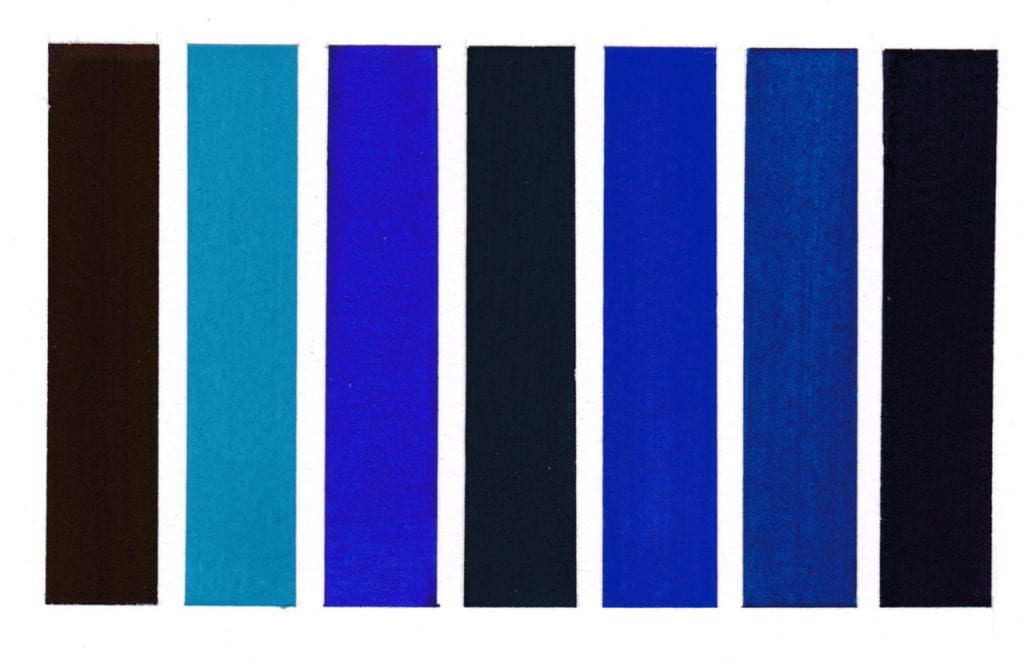

The arrangement of this week’s colours is taken from Agnes Denes’ poem Colors of the Week* and features David Dobson’s 2017 invention Deep Water Blue pigment. David explains.

‘The colours of the common minerals are dominated by the presence of iron. Iron atoms in minerals take on two charges, loosing either two or three electrons to make ferrous (Fe2+) or ferric (Fe3+) iron. Iron oxides and hydroxides commonly contain mixed valence states and exchange of electrons between the ferric and ferrous states produces the reds and yellows seen in the earth pigments. In silicate minerals, such as olivine, iron replaces divalent magnesium and Fe2+ dominates. In this case electronic transitions localised on the iron ion causes olivine to have pale green colours. Very occasionally charge transfer between iron ions in ferric and ferrous states can cause blue colouration. Vivianite is an iron phosphate where the iron is in the 2+ state. When fresh it is colourless, however exposure to air causes some oxidation to iron 3+, some of which which sits on the tetrahedral phosphate site and a blue colour develops quite quickly. It seems that this tetrahedral ferric iron might be the key to making iron-based blues. Ringwoodite is a vibrant blue silicate spinel which is stable between 520 and 660 km depth in the Earth. In this case the colour only develops when there is a charge-coupled substitution of Fe3+,H+ onto the tetrahedral Si4+ site. This substitution is quite easy in ringwoodite, and if all of the Earth’s ringwoodite were fully hydrated it would contain something like 4 times the amount of water in the oceans. The Deep Water Blue pigment uses silicate and germanate structures which can take significant amounts of ferric iron on tetrahedral sites to reproduce the colour of ringwoodite.’

David Dobson is a geologist, mountaineer and print-maker. He is interested in process, whether that is the chain of action linking winter mountaineering to a final image or developing new pigments. He is also a professor at UCL, Earth Sciences and the first Slade Scientist in Residence 2018-19

Instagram:@m3m_works

YouTube: One Minute Geology

Image: Fe-Mg ringwoodite David Dobson

THE COLOR OF MONDAY IS WHITE

Lithopone

THE COLOR OF TUESDAY IS YELLOW

Turmeric

THE COLOR OF WEDNESDAY IS ORANGE

Persian Orange

THE COLOR OF THURSDAY IS GRAY

Grey Rose

THE COLOR OF FRIDAY IS BLUE

David Dobson’s Deep Water Blue

THE COLOR OF SATURDAY IS BROWN

Brown-Red Slate

THE COLOR OF SUNDAY IS RED

Cinnabar

IT HAS BEEN THAT WAY ALL MY LIFE.

*Thanks to Lesley Sharpe for directing me to this poem.

Today is both International Colour Day & World Poetry Day and the eve of World Pigment Day established in 2020 by Ruth Siddall and myself. This project started on 23rd March 2020 in an attempt to celebrate and document it’s initial year by simply dedicating a painted swatch of colour to each day and pure coincidence it was also the first day of lockdown in the UK but has somehow documented this most extraordinary year. It was inspired by A Boogert’s C17 educational manual of how to mix every colour available and influenced by Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours with Patrick Syme’s amendments. A Colour A Day is now finished (I hesitate to say complete as I haven’t painted every colour available to me in my studio) and later in the year they will be made into a series of digital prints and a publication.

Thank you to all of you who have sent me pigments and paints, writings and poems to include.

Close

Close

*I first became aware of Yin MIn Blue in the summer of 2016 and wrote to the manufacturers requesting a sample for the Slade Material Research Project Pigment Collection but without luck. I then discovered a paint manufacturer in Australia, Derivan, were advertising it in their Matisse range as Oregon Blue and wrote a similar email asking for a donation. This is response from Steven Patterson, Derivan’s Chief Executive Officer that summer.

*I first became aware of Yin MIn Blue in the summer of 2016 and wrote to the manufacturers requesting a sample for the Slade Material Research Project Pigment Collection but without luck. I then discovered a paint manufacturer in Australia, Derivan, were advertising it in their Matisse range as Oregon Blue and wrote a similar email asking for a donation. This is response from Steven Patterson, Derivan’s Chief Executive Officer that summer.