A Manual Alphabet for the Deaf and Dumb, circa 1870s

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 14 July 2017

You may wonder what happened to the archive material from Margate School when it closed. I cannot give a full answer as I do not know exactly what Margate had in the way of records, but broadly as far as I am aware the school and pupil records went to the Kent County Archives in Maidstone, while I believe that a full set of annual reports, and perhaps some other material, went to the British Deaf History Archive in Warrington. I suppose that they are both in the process of organising and cataloguing that material. What we took was only a few boxes of books that we are sorting through to fill any gaps in our collection. Most of these we already had, and unless you are an expert in the area of the history of education these are mainly rather dull and dry books!

You may wonder what happened to the archive material from Margate School when it closed. I cannot give a full answer as I do not know exactly what Margate had in the way of records, but broadly as far as I am aware the school and pupil records went to the Kent County Archives in Maidstone, while I believe that a full set of annual reports, and perhaps some other material, went to the British Deaf History Archive in Warrington. I suppose that they are both in the process of organising and cataloguing that material. What we took was only a few boxes of books that we are sorting through to fill any gaps in our collection. Most of these we already had, and unless you are an expert in the area of the history of education these are mainly rather dull and dry books!

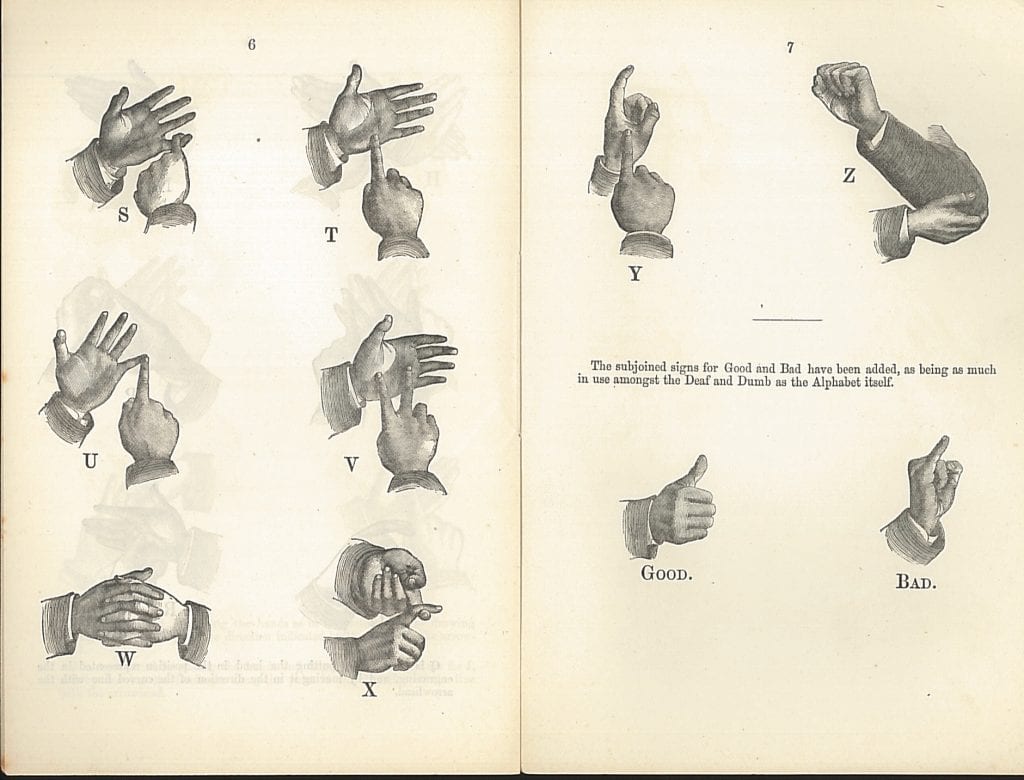

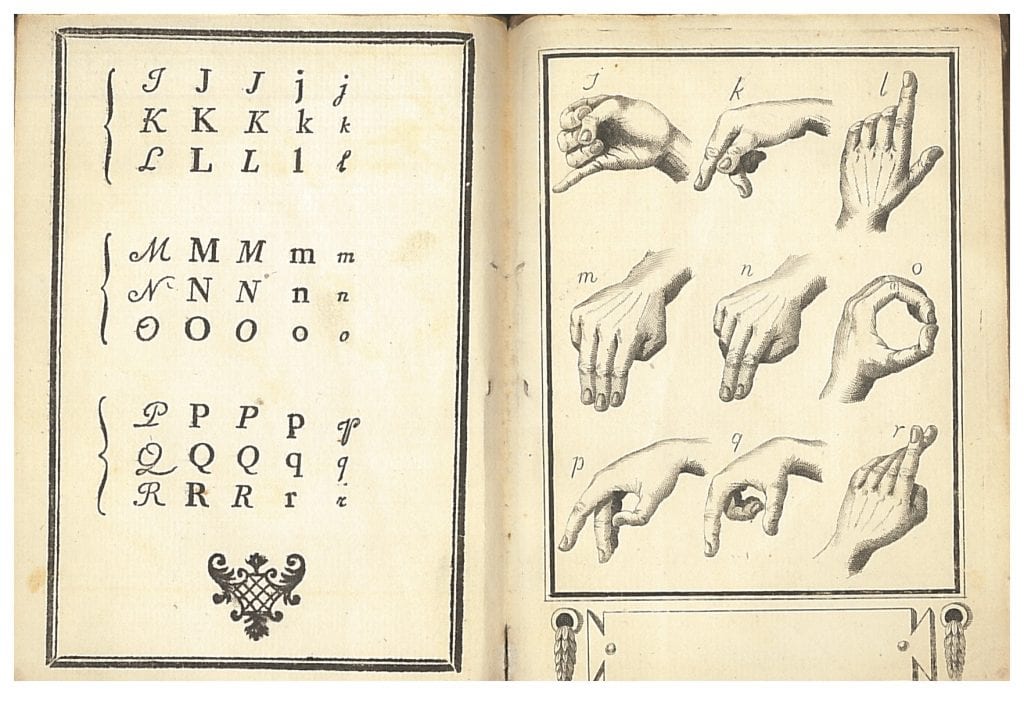

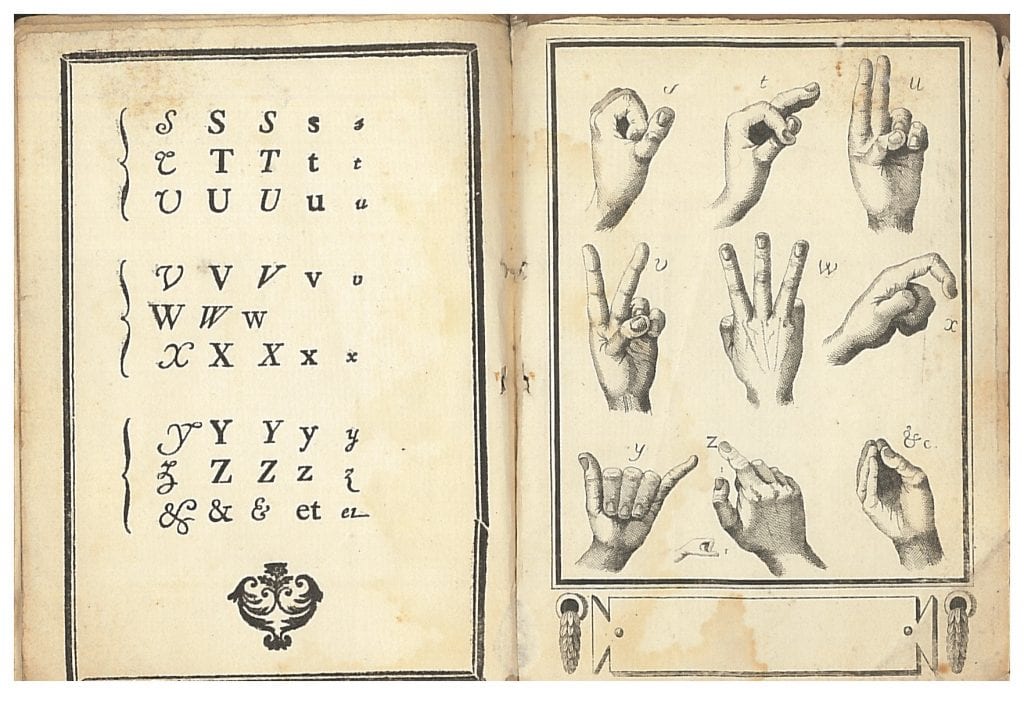

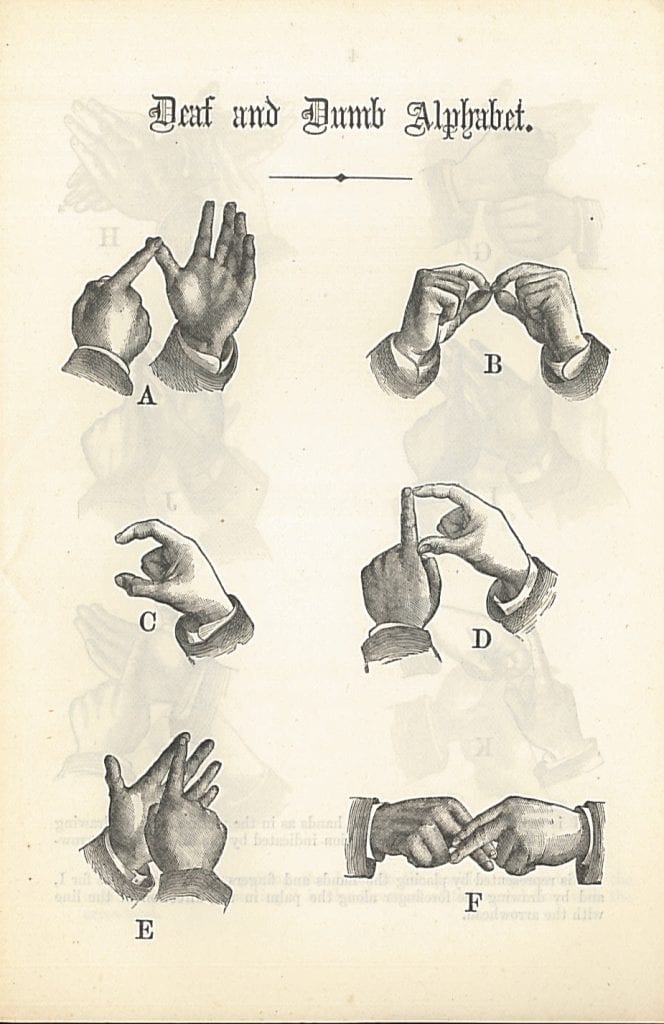

There are a couple of gems however. This beautifully produced booklet, A Manual Alphabet for the Deaf and Dumb, […] sold at the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, Old Kent Road… came to us from the Margate School. I am a little surprised that we have not got it, though it is possible we have a copy – it is all a question of how it is described in the catalogue, so it could already be lurking in the collection. In the past the librarians used brown card and stapled many smaller loose items, of what we call ‘grey literature,’ into these covers. Grey literature can cover a multitude of things – but it would usually mean something that was not a book or a journal, or a report. It could be a reprint of an article, a booklet, a single page, and so on. I suppose they were doing what they thought was right, protecting the items and making them available for general use. We would not do this now – rather, we would put these leaflets or booklets in a box.

There are a couple of gems however. This beautifully produced booklet, A Manual Alphabet for the Deaf and Dumb, […] sold at the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, Old Kent Road… came to us from the Margate School. I am a little surprised that we have not got it, though it is possible we have a copy – it is all a question of how it is described in the catalogue, so it could already be lurking in the collection. In the past the librarians used brown card and stapled many smaller loose items, of what we call ‘grey literature,’ into these covers. Grey literature can cover a multitude of things – but it would usually mean something that was not a book or a journal, or a report. It could be a reprint of an article, a booklet, a single page, and so on. I suppose they were doing what they thought was right, protecting the items and making them available for general use. We would not do this now – rather, we would put these leaflets or booklets in a box.

As you will know if you have ever found an old magazine that has been in slightly damp conditions, old staples can often rust and break leaving a nasty stain on the paper. This particular booklet is stitched rather than stapled. The staple was an ancient device but it was not until the late 19th century that staples for paper were invented, so if you are trying to date something and it is stapled, it probably dates from after 1880.

Cataloguers would not I hope be offended if I were to say they have a particular ‘attention to detail’ – to put it bluntly, they are pernickety. Therefore, while cataloguers will often differ in detail when they categorize a book, overall I trust them. That is why we often use the combined catalogue COPAC which covers major British and Irish universities and academic institution collections. It is a useful tool to see where a rare item is held, and how it has been classified. This is how Cambridge (top) and Dublin Trinity College (below) have described it:

A manual alphabet for the deaf and dumb. London ; Paris ; Madrid : Baillière, Tindall, & Cox [1872?]

A manual alphabet for the deaf and dumb. London, Paris and Madrid : Baillière, Tindall & Cox [ca. 1880]

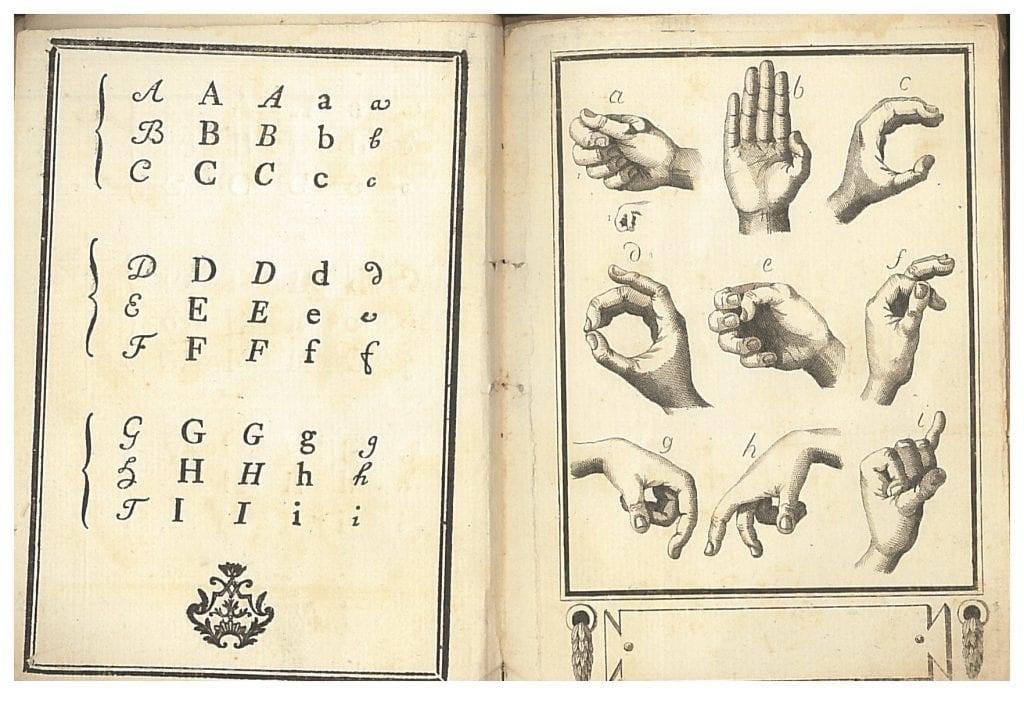

As you see, they disagree about the date, and though it might be possible to narrow that with some diligent research. Some Baillière archives are at Reading University.  Note the way ‘Q’ is signed.

Note the way ‘Q’ is signed.

Close

Close