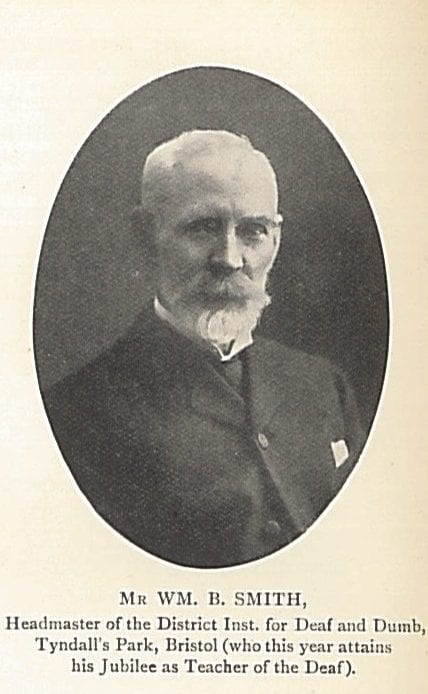

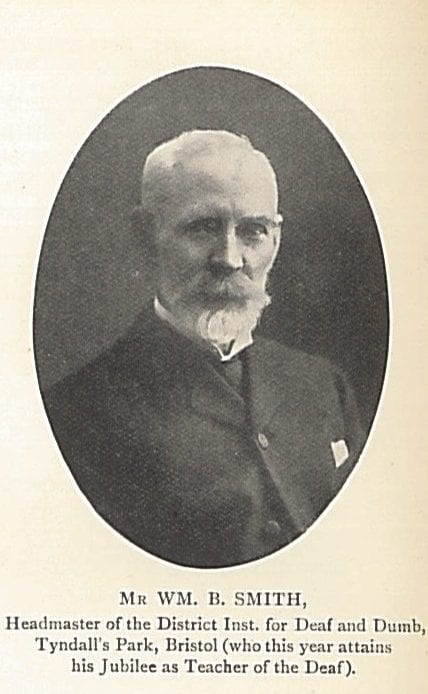

William Barnes Smith (1840-1927) was a younger brother of the Rev. Samuel Smith, first vicar of St. Saviour’s, and missioner to the Deaf of London. He was born in Leicestershire, and spent 54 years teaching up to his retirement in 1908. His older brother was the Rev. Samuel Smith, of St. Saviour’s London. William trained under Charles Baker of Doncaster, then worked under Andrew Patterson at Manchester before spending 12 years with Dr. Buxton at Liverpool. In 1873 he was appointed headmaster of the Bristol Institution (see obituary). He also acted as Secretary to the Bristol Mission for the Deaf after retirement. His son Alfred G. Smith trained at the Fitzroy Square Training College, then became headmaster of the Osborne Street School for the Deaf, Hull (Teacher of the Deaf, 1915, vol. 13, p. 27).

William Barnes Smith (1840-1927) was a younger brother of the Rev. Samuel Smith, first vicar of St. Saviour’s, and missioner to the Deaf of London. He was born in Leicestershire, and spent 54 years teaching up to his retirement in 1908. His older brother was the Rev. Samuel Smith, of St. Saviour’s London. William trained under Charles Baker of Doncaster, then worked under Andrew Patterson at Manchester before spending 12 years with Dr. Buxton at Liverpool. In 1873 he was appointed headmaster of the Bristol Institution (see obituary). He also acted as Secretary to the Bristol Mission for the Deaf after retirement. His son Alfred G. Smith trained at the Fitzroy Square Training College, then became headmaster of the Osborne Street School for the Deaf, Hull (Teacher of the Deaf, 1915, vol. 13, p. 27).

On the 20th of June, 1864, William B. Smith bought a copy of The physical, Moral, and Intellectual Constitution of the Deaf and Dumb: with some practical and general remarks concerning their education. I know this as he wrote that in ink on the title page, pencilling ‘Liverpool’ underneath. Later, he wrote his name and address inside the front cover – 5 Rokeby Avenue, Bristol . He later gave the book to Selwyn Oxley. This book, which had been published in London in 1863, was written by James Hawkins (1830- after 1891). Hawkins was born in Wolvercut, Wolvercott, or Wolvercote, Oxfordshire, in about 1830. I do not know how he came to become a teacher of the deaf (perhaps a thorough search of various surviving records might illuminate that), but by the 1851 census he was an assistant teacher at the Old Kent Road Asylum, along with George Banton, (b.ca. 1812), Edward J Chidley (b. 1819), Edward Buxton (b.ca. 1826), William Stainer (b. 1828), Charles Toy (b.ca. 1832), Alfred Large (b.ca.1835), and Emma Rayment (b.ca. 1829).

The present crude state of all physiological, as well as pathological science, necessarily renders very conjectural any remarks upon the origo mali, or the phenomena of disease. The fall of Adam is one of the most favourite of the theories which are nursed by Divines and others, in an excess of Hutchinsonian zeal; and to this ‘excellent foppery of the world,’ as Shakespeare has it, they like to attribute every bodily affliction and mental evil that can happen to mankind. Argumentative reasoning, however (of this kind especially), shows ‘an indiscreet zeal about things wherein religion is not concerned,’ as weak as it is undoubtedly fallacious, and affords them but a poor ‘coigne of vantage;’ for the majority of our inborn and acquired calamities are ofttimes none other than the ‘surfeit of our own behaviour,’ the spontaneous results of injury done to the functions of the body, by throwing its natural and complex organization out of gear, and not, as many would make us believe, always direct constitutional imprints of the Creator’s anger on his creatures. (Hawkins, 1863, Preface, p.iii-iv).

Hawkins must have had a good education. In his preface alone he mentions Paley and Malthus, as well as quoting Ovid and, perhaps ingenuously, “no cormorant for fame,” Peter Pindar. The names of more classical authors are dropped in when opportunity allows. He cites Niebuhr, who

called the office of the schoolmaster one of the most honourable occupations of life. He could well have added, and one in which a thorough manliness of character is also most essential; for there is not one where all the manly virtues are more called into exercise. Moral courage, unsullied reputation and integrity, sound religious principles, firmness of purpose and gentleness of demeanour ought ever to be his most distinguishing traits, if he aspire to any degree of eminence in his profession. (ibid, p.98)

It is all the more poignant then, that for some reason, by 1871, when he was living in Greenwich with Charles Henry James, Harbour Master at the Port of London, he was ‘unemployed’, and ‘formerly Assistant Teacher to the Deaf & D. Institute’. I wonder what caused him to be dismissed. Did his book upset people? It would seem unlikely that a book published eight years earlier might cause his dismissal. Is it possible he was tutoring Ellen James, who was deaf, though by then aged 25? In the 1881 census he was a ‘wholesale stationer’ visiting the James family. It looks as if something or someone destroyed his life as a teacher. If you discover more about James Hawkins, who does not seem to have married, and who I cannot find after the 1891 census when he was a visitor in St. Pancras, please comment.

Here is a page from the text. Click to enlarge.

Smith

Obituary, Mr. W.B. Smith, The Teacher of the Deaf, 1927, vol. 25 p.35

Hawkins

Hawkins, James, The physical, Moral, and Intellectual Constitution of the Deaf and Dumb: with some practical and general remarks concerning their education. 1863, Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, London

1871 Census – Class: RG10; Piece: 758; Folio: 34; Page: 31; GSU roll: 824727

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 1509; Folio: 41; Page: 5; GSU roll: 1341364

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 139; Folio: 71; Page: 1; GSU roll: 6095249

*”This is the excellent foppery of the world that when we are sick in fortune—often the surfeit of our own behavior—we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars, as if we were villains by necessity, fools by heavenly compulsion, knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical predominance, drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforced obedience of planetary influence, and all that we are evil in by a divine thrusting-on.” Edmund in King Lear.

Close

Close