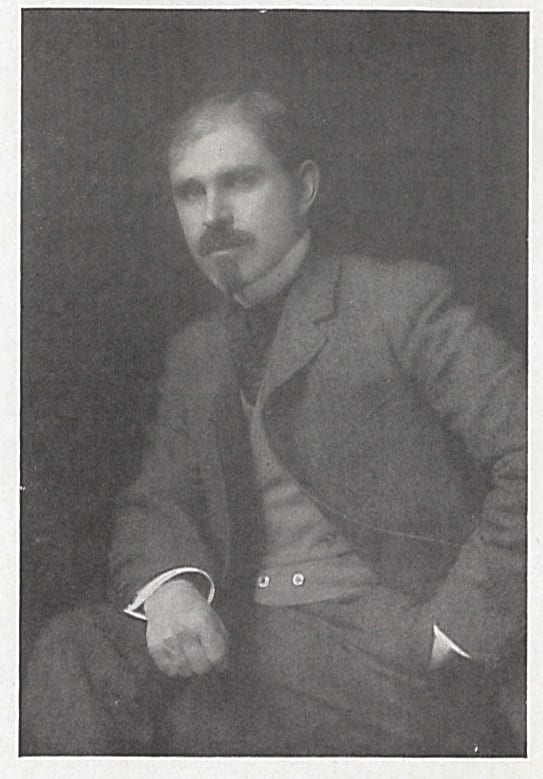

Earnest Elmo Calkins, Deaf Pioneer of Modern Advertising

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 24 November 2017

Earnest Elmo Calkins (1868-1964) was a pioneer of modern advertising. Born in

Earnest Elmo Calkins (1868-1964) was a pioneer of modern advertising. Born in

In Design Observer, Steven Heller says of him, that he is “recognized as the founder of “styling the goods,” otherwise known as “consumer engineering” or even better known as “forced obsolescence”—he is considered in the pantheon of twentieth century Modernists.”

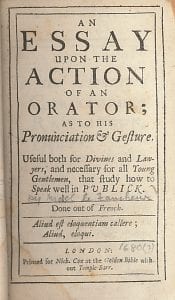

Calkins wrote a volume of memoirs, “Louder Please,” in 1924, & then in 1946 produced an extended version, “and hearing not-“; Annals of an Adman. Writing in the third person, here as ‘the Boy,’ he describes here his loss of hearing in a chapter that appears in both volumes, ‘The ears begin to close’ :

nothing stands out with any sharpness, either teachers or lessons. A sort of mist seems to veil the next three or four years.

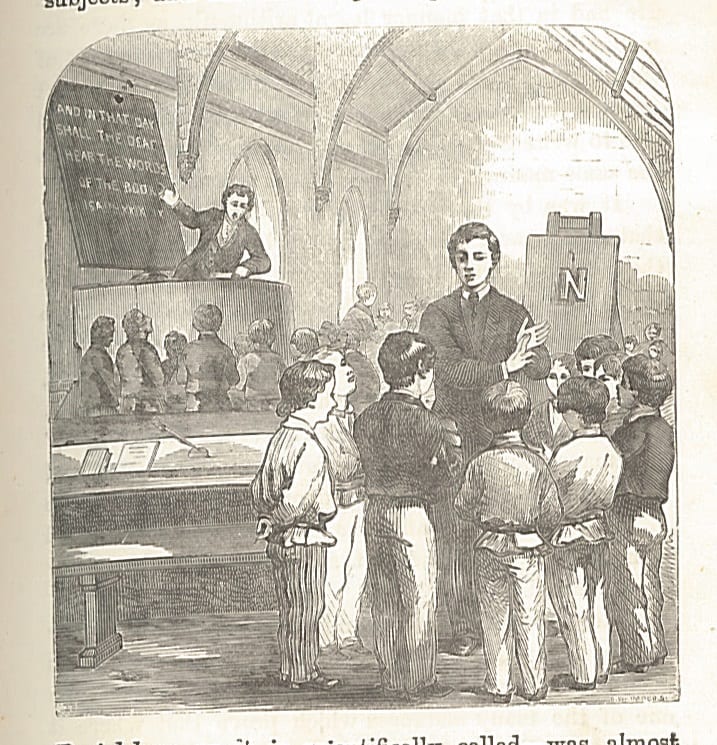

The reason for the mist was that the Boy was growing deafer. School seemed more futile the less he heard of it. The world-old conflict between heredity and environment was henceforth to be influenced by a new element whose effect could not be foreseen. Deafness introduced complications that required new adjustments, like deuces wild in a poker game. The cause, it seems, was measles experienced at the age of six, at length bearing its evil fruit, but the predisposition was probably a part of his inheritance. He was at least ten years old before his condition was realized, even by himself. His fits of abstraction and oblivion were laid to inattention by the higher powers, both at home and abroad. (and hearing not, p.p.67-8)

He went on eventiually to college, and got good marks in mathematics, but otherwise, “For four years he sat in various classrooms, hearing almost nothing, content or at least resigned to make out a passable performance” (p.100). He got into advertising aged 23, when he won a competition for an advertisement for a Bissell carpet sweeper. Later on his advertising company was behind ‘Lucky Jim’ of the breakfast cereal Force, and he introduced modern art into American advertising in the 1920s.

In the chapter, ‘Social life of a deaf man,’ Calkins describes how so many famous people he met he was “unable to use, other than to satisfy my curiosity as to how they looked.” He relied on his wife in many of these situations (p.180). He says that “Deafness was the ever present influence. It made or marred my attempts to earn a living, it selected my friends for me, and determined what I was to enjoy of social life, what my amusements were to be.” (p.181)

In the chapter, ‘Social life of a deaf man,’ Calkins describes how so many famous people he met he was “unable to use, other than to satisfy my curiosity as to how they looked.” He relied on his wife in many of these situations (p.180). He says that “Deafness was the ever present influence. It made or marred my attempts to earn a living, it selected my friends for me, and determined what I was to enjoy of social life, what my amusements were to be.” (p.181)

“A partially deaf man is like Aesop’s bat, neither animal nor bird, but having the disabilities of both, belonging neither to the hearing world nor that of the totally deaf.” (p.188)

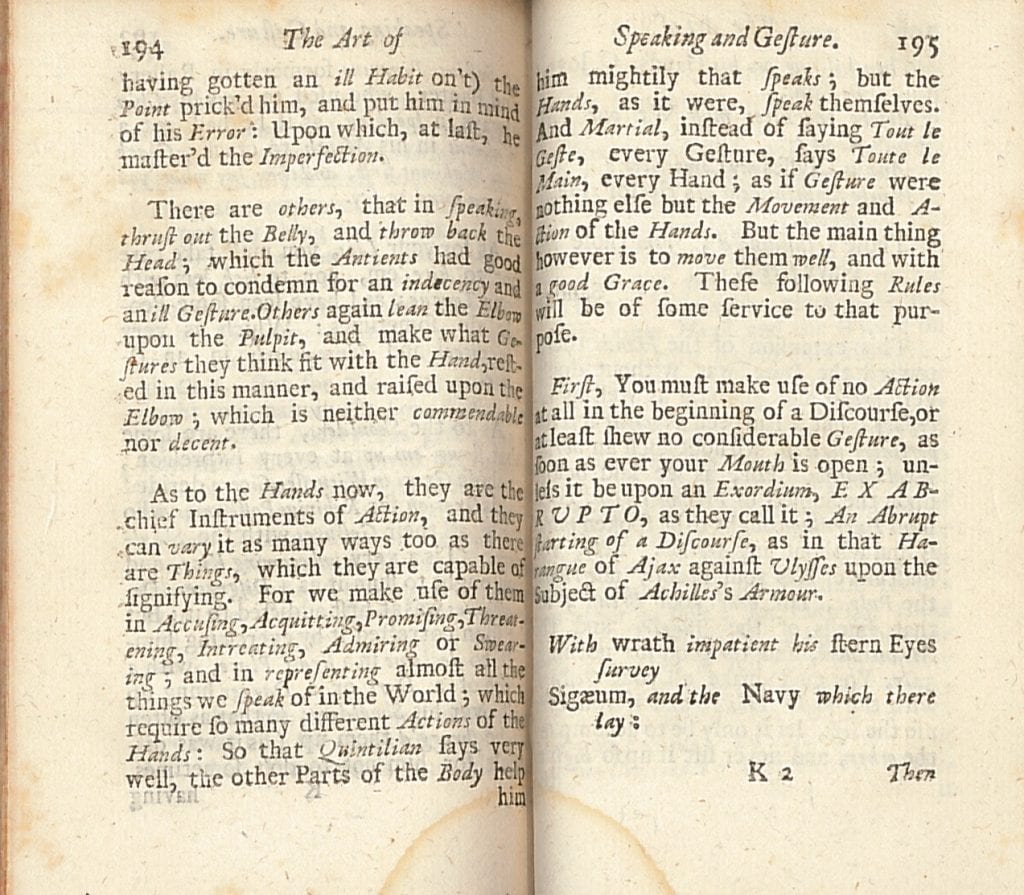

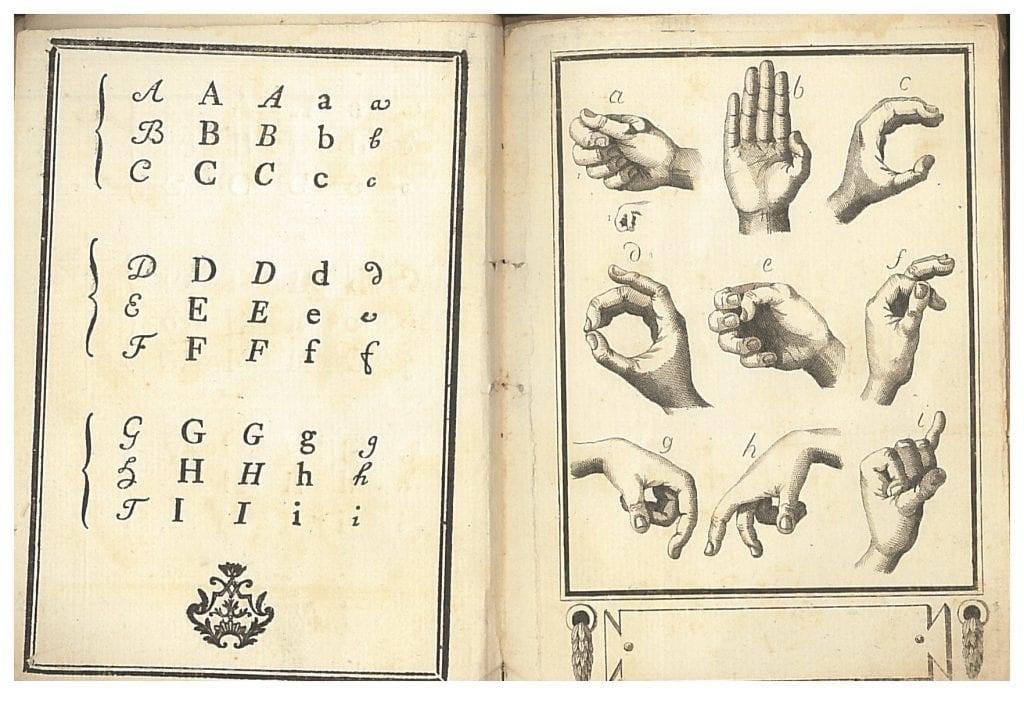

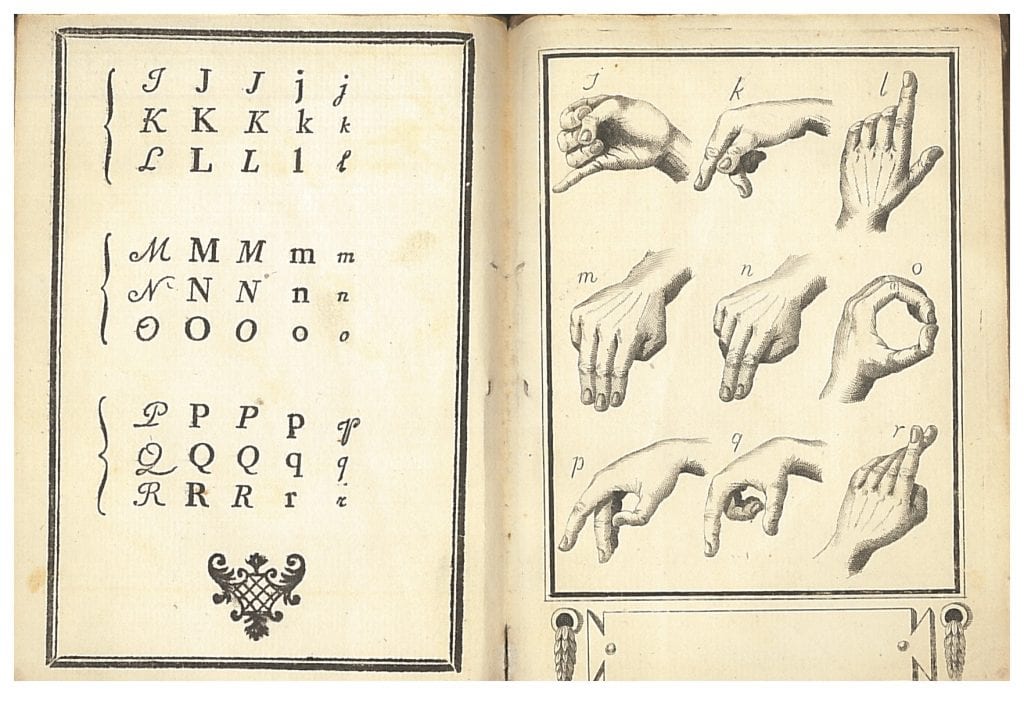

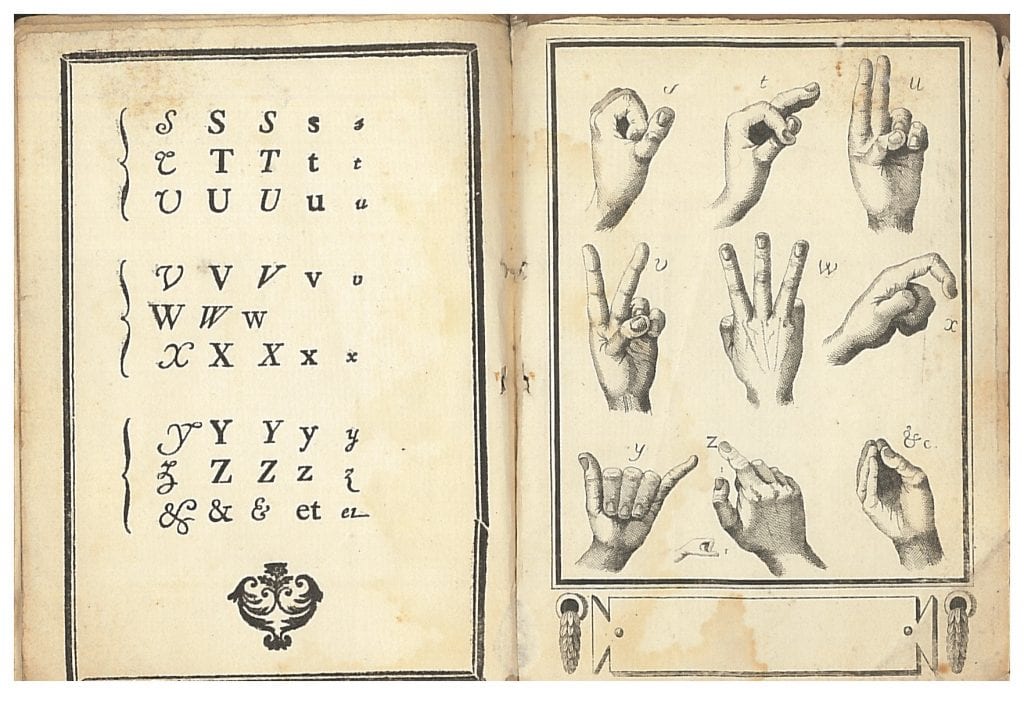

“Lip reading is like handwriting in that it is sometimes as clear as print and again as illegible as Horace Greeley‘s famous chirography.” (p.189) He had lessons in lip reading with Edward B. Nitchie, who was deaf and whose books we have.

We have the two volumes of memoir mentioned above. One is signed by Calkins, dedicated to Madeleine de Soyres. They are well worth investigating, and he seems to me an engaging writer.

Calkins, Earnest Elmo, “Louder Please,” 1924

Calkins, Earnest Elmo, “and hearing not-“; Annals of an Adman. New York, 1946

Close

Close