Rosina Fanny Oliver Hinckley was the daughter of a pesioned navy sailor, George Hinckley of Liverpool, and his Cornish wife, Jane. At some point after the 1871 census when she was three and her brother George was 2, it must have been discovered that they were both deaf. They were both educated at the Exeter Institution, as we can see from the census for 1881. after school, George became a tailor and Rosina a milliner.

Rosina Fanny Oliver Hinckley was the daughter of a pesioned navy sailor, George Hinckley of Liverpool, and his Cornish wife, Jane. At some point after the 1871 census when she was three and her brother George was 2, it must have been discovered that they were both deaf. They were both educated at the Exeter Institution, as we can see from the census for 1881. after school, George became a tailor and Rosina a milliner.

John Lethbridge was born in Tavistock, Devon in 1871, son of George Lethbridge, a painter and paper hanger in 1881, and his wife Margaret (née Stevens). He is not described as deaf in the census returns until the 1891 census when he was twenty. He became a boot finisher.

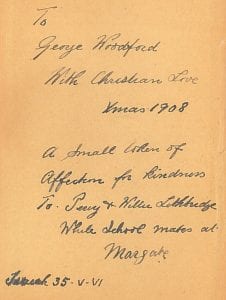

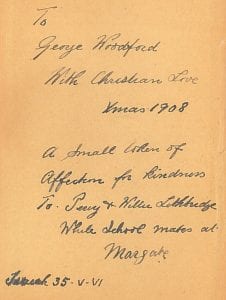

Rosina married John Lethbridge in 1893. Presumably they were acquainted through the local Deaf community in Plymouth, although there was no formal deaf mission there until 1897. They had nine children, two of them dying in childhood. At least four of the surviving children were deaf, Percy and Willie, and Olive and Elsie. What set me onto this family, was the dedication in a book which we have. The book, by ‘C. J. L.’ (Caroline J. Ladd) is Deaf, Dumb and Blind – True stories of child life (1902). As you see here, the inscription reads,

To George Woodford

To George Woodford

With Christian love

A small token of

affection for kindness

to Percy and Willie Lethbridge

While school mates at

Margate

Isaiah 23-V-VI*

The book is rather twee for modern taste. Chapter five, ‘What could Susie do for Jesus?’ tells us about a Deaf girl who,

‘was a first class girl, now “quite an old scholar,” as she often told those who understood her silent language.’ (p.40) […]

Susie was much interested in being told about the poor children of India by a teacher who was leaving B. to take charge of a mission school in that far-off land. She seemed much troubled on hearing that great mumbers of Hindoo children did not know anything about the true God, but prayed to idols, saying, on her fingers, “Oh do tell about the Lord Jesus Christ, and I will pray to Him for you and for all the girls who attend your school.” And on being told it was very likely, as the number of deaf mutes in India is very large, asked if she might send her favourite doll to some Indian girl afflicted in the same way as herself, and was quite delightedwhen told it should be packed with some books, toys, and other things friends were sending for the mission school, and given with Susie’s love to a deaf and dumb child. (ibid, p.45-6)

Note the language the writer uses, deafness and blindness as ‘affliction.’ I think this may be a true story, or based on one, and that Susie was probably at school in Birmingham. It might be possible to investigate further to see if we could identify that teacher. I have not been able to narrow down Caroline Ladd, so please comment if you have come across her somewhere.

It was relatively easy to find the Lethbridge brothers in the 1911 census, then discover that they were from what we might call a culturally Deaf family. In their recent book, People of the Eye (OUP, 2011), Harlan Lane, Richard Pillard and Ulf Hedberg describe the American ASL Deaf community as a type of ethnicity, where the primary language is signs, as distinguished from the deaf who are not . We can, perhaps, extend that idea to B.S.L. users in the U.K. It would be interesting to know if that were the case for the extended Lethbridge family.

It was relatively easy to find the Lethbridge brothers in the 1911 census, then discover that they were from what we might call a culturally Deaf family. In their recent book, People of the Eye (OUP, 2011), Harlan Lane, Richard Pillard and Ulf Hedberg describe the American ASL Deaf community as a type of ethnicity, where the primary language is signs, as distinguished from the deaf who are not . We can, perhaps, extend that idea to B.S.L. users in the U.K. It would be interesting to know if that were the case for the extended Lethbridge family.

In 1901, the Lethbridge family had a lodger, James John Weeble, who was also Deaf, and, as a ‘boot riveter’ was presumably a friend and colleague of John Lethbridge.

Rosina died in Plymouth in 1960, aged 92. Her husband John ahad died in 1912 – so she was a widow for 48 years, with a large family. Percy died in 1962, but I am not sure when Willie died. If you use the www.ancestry.co.uk you will see relatives and descendants have produced a detailed Lethbridge and Hinckley family tree, with photos.

The person I have not mentioned is George Woodford, to whom the book was given. He was the father of Doreen Woodford (a person whose name will be familiar to anyone in the British Deaf community) and was some years older than the Lethbridge boys, being born in 1893, so would have been fourteen at the time of the gift.

*Then will the eyes of the blind be opened and the ears of the deaf unstopped.

‘C. J. L.’ (Caroline J. Ladd) Deaf, Dumb and Blind – True stories of child life (1902)

Woodford, Doreen E., Who’s interpreting on Sunday morning? (2010)

1871 Census – Hinckley – Class: RG10; Piece: 2139; Folio: 115; Page: 59; GSU roll: 832034

1871 Census – Lethbridge – Class: RG10; Piece: 2147; Folio: 60; Page: 52; GSU roll: 832037

1881 Census – Lethbridge – Class: RG11; Piece: 2197; Folio: 16; Page: 25; GSU roll: 1341529

1881 Census – Hinckley – Class: RG11; Piece: 2152; Folio: 123; Page: 43; GSU roll: 1341519

1891 Census – Hinckley – Class: RG12; Piece: 1741; Folio: 46; Page: 48; GSU roll: 6096851

1891 Census – Lethbridge – Class: RG12; Piece: 1725; Folio: 24; Page: 42; GSU roll: 6096835

1901 Census – Lethbridge – Class: RG13; Piece: 2110; Folio: 36; Page: 64

1911 Census – Margate School – Class: RG14; Piece: 4501

1911 Census – John and Rosina Lethbridge – Class: RG14; Piece: 13020; Schedule Number: 127

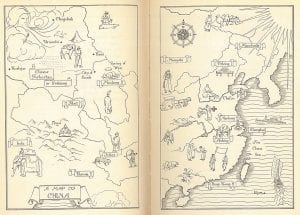

Frances Margaret Parsons and Hester West Parsons were deaf twins from El Cajon, California. They were born in 1923 and it was not realized that they were deaf until they were five, or perhaps they lost their hearing aged five (see links at end). The sisters were sent to the State School for the Deaf at Berkeley, but their father lost his job in the depression. Their mother, Hester Tancre Parsons, missed her daughters who were boarding, and conceived a plan to move the family to Tahiti, which they did in 1935.

Frances Margaret Parsons and Hester West Parsons were deaf twins from El Cajon, California. They were born in 1923 and it was not realized that they were deaf until they were five, or perhaps they lost their hearing aged five (see links at end). The sisters were sent to the State School for the Deaf at Berkeley, but their father lost his job in the depression. Their mother, Hester Tancre Parsons, missed her daughters who were boarding, and conceived a plan to move the family to Tahiti, which they did in 1935. http://www.vad.org/Frances_Parsons_Lecture.html

http://www.vad.org/Frances_Parsons_Lecture.html Close

Close