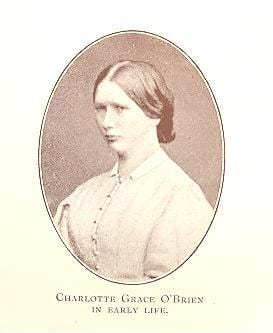

Charlotte O’Brien was born on 23rd of November 1845 into an Anglo-Irish protestant family that was a branch of the Dromoland O’Brien Baronets. Her father William was an M.P. and Young Ireland nationalist moved by the great famine to take part in the 1848 rebellion. He was condemned to be hanged drawn and quartered for treason but was however reprieved and allowed to return to Ireland after a period in exile. All of his children had some hearing problems, with his son William being deaf from birth. Charlotte had a form of progressive hearing loss, and as we see from her poem below (dated 1879) by her mid 30s she had become deaf.

Charlotte devoted many years to helping the poor emigrants who were pushed off the land firstly by the famines and then by other social pressures. These people had to endure further privations in lodging houses and then on board ships to America and Australia, and she tried to alleviate their suffering. Her nephew says in his memoir (1909, p.75),

Charlotte devoted many years to helping the poor emigrants who were pushed off the land firstly by the famines and then by other social pressures. These people had to endure further privations in lodging houses and then on board ships to America and Australia, and she tried to alleviate their suffering. Her nephew says in his memoir (1909, p.75),

None of her letters tell of the sharp struggle she had to face in Queenstown itself when she actually started. […] when she and her man John went down to the station to meet arrivals they were hustled violently and threatened with worse. She described to me a perfect pandemonium, poor creatures from the wilds of Kerry or Connaught emerging like cattle from the crowded carriages, sick with hunger or fatigue, stupefied with grief ; and then the mob of lodginghouse runners seizing them, dragging them this way and that, with noisy exhortations.

Thus she began her work of love in a turmoil of mean and jealous hatred, bullied and browbeaten.

Charlotte was criticised for helping emigrants who accepted the £5 ‘bribe’ that some English philanthropists paid to every person who would leave. This was seen by nationalists as a form of social engineering to remove trouble makers. She went to America to promote her cause. Here is her nephew Stephen Gwynn again (ibid. p.86);

when I look on the record of her work in America, as I find it in old newspaper cuttings, it is amazing how little physical disabilities weighed on her. She had never spoken in public; yet she addressed great audiences successfully; she was extremely deaf, yet she went everywhere making acquaintances, making friends, entering into the whole life of the place as very few women could do with every natural advantage.

Continuing to write all her life, she was however never successful at it according to Gwynn, for “She was too busy living to concentrate her powers on the special task of bringing an art to it’s completeness.” Charlotte’s best work is where she was constrained by metre he says. He calls her writings on deafness “vehement Brontësque outpourings: and of such there is a good deal among her unpublished papers, though none else so poignant.” (ibid. p.131-2)

She died in 1909 having converted to Roman Catholicism. Back in Ireland she did a lot of work on the botany of her beloved Limerick.

The important thing about her is “not what she did but what she was” says Stephen Gwynn (ibid.p.133-4), but “a true portraiture would show, I think, two chief excellencies, a nature unstunted by an infirmity which went to the very core of life, and a passionate love of her country with a sense of kinship with its poorest people.”

DEAFNESS THE PAST AND THE PRESENT

The woods are silenced for me, and the streams

Ripple no more for me along the leas;

No more for me the birds sing melodies

To greet the morn, or give the sun good dreams;

No more the circling rooks in heavy crowds

Beat homeward cawing, ‘neath the wind-swept clouds.

Where are the sweet sounds gone ? Are they all gone ?

Gone from the meadows deep with swathes of hay:

There the blithe corncrake woke the summer day.

Or startled the still air the whole night long.

Now silent in their beauty they bend low

While the rich-scented breezes o’er them blow.

Oh ! merry voices of the world of life,

From the warm farm, the byre, the hen-roost shed ;

There nesting swallows flashed above my head,

And all about the air with sound was rife;

With din of sparrow hordes, incessant, shrill,

Debating, scolding, loving then so still.

So still, for I had called them ! Breathlessly

I stood awaiting the oncoming burst

And rush of rival voices, all athirst

To fill the air with carols mad with glee

Set with dark globes and crowns, the burnished leaves

Now sway in silence ‘neath the silent eaves.

O earth ! what murmurs sweet beguile thy rest,

Ere yet the thrush his glorious matin rings;

Ere yet the goldfinch on his glittering wings

Brushes the jasmine stars from round his nest;

Ere yet the daisy leaves turned toward the sun,

Bid night ” Good night,” and speak his day begun.

Oh, bitter loss ! all Nature’s voices dumb.

Oh, loss beyond all loss ! about my neck

The children cast their arms; no voices break

Upon my ear; no sounds of laughter come

Child’s laughter, wrought of love, and life, and bliss;

Heedless I leave the rest, had I but this !

1879.

For me, her best poem is ‘Glenville’ –

The shadows flicker on the coltsfoot sheaves :

There ‘neath the bridge and o’er the sparkling stream,

Often we traced the water’s wavering gleam

Amid long trailing branches and green leaves ;

Often we rested, where the beech tree weaves

A liquid web for every wandering beam

O’er deep dark pools wherein the old trout dream,

And oft a shining foot the water cleaves.

A stream o’ergrown and shadowed all its length,

From the fairy fort and glen, to the old bridge,

Bringing its amber waters from the strength

Of yonder brown, bare, boggy, heathery ridge,

To where the fat land’s heavy-footed kine

In their rich beds of luscious green recline.

The library copy of her book shows it came from a member of her family – her cousin was Professor Stockley.

The library copy of her book shows it came from a member of her family – perhaps a niece?

http://www.limerickcity.ie/media/Media,4182,en.pdf

http://www.limerickleader.ie/news/local/worthies-of-thomond-no-3-charlotte-grace-o-brien-1-2186248

http://herbariaunited.org/collector/12644/

Gwynn, Stephen, Charlotte Grace O’Brien; selections from her writings and correspondence, with a memoir by Stephen Gwynn. Dublin, 1909

Close

Close