‘I said to her, “The child’s head is cut off.” I have seen her several times since, and she still insists that the head came off.’ Esther Dyson 1807-1869

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 29 November 2019

William Dyson (baptised 1804) and his sister Esther, were born in Ecclesfield, Yorkshire, and were both Deaf. They were children of Isaac and Hannah Dyson, and Esther was the youngest of eight. I do not know the fates of all the children, but one of the newspapers said that they had no parents or siblings surviving in 1831, though there were other Dysons still in the village. I came across Esther’s story in the newspaper archive, and it is a sorry tale of neglect. I will leave it to the papers to tell the story.

CHILD MURDER. Sheffield, Sept. 30.

Some excitement has been occasioned in Sheffield and the neighbourhood for the last two days, in consequence of the discovery of child murder, young woman, 23 years of age, at a village called Ecclesfield, on the road to Leeds from Sheffield. The accused person is Esther Dyson, a deaf and dumb girl, working at a thread-mill at that place, girl of exceeding good appearance, and remarkably shrewd and cunning.

THE INQUEST.

On Thursday, a respectable body of men assembled at the house of Mr. Ashton, the Black Bull Inn, in Ecclesfield, near Sheffield, before Mr. B. Badge, coroner for that district of Yorkshire, on view of the body of the child, when the following evidence was adduced -Ellen Greaves, the wife Thomas Greaves, of Ecclesfield, in the county York, file-cutter, deposed – I knew Esther Dyson, single woman, who is about 23 years of age; she is deaf and dumb ; I live next door to her, and she lives with her brother, who is also deaf and dumb. Three or four months ago I challenged her with being in the family way, but she denied it; she has sufficient knowledge, in my opinion, to know what is right or wrong, and I can make her understand by signs what I mean. About a month ago I again challenged her with being with child, and she seemed angry with me, and she told me signs that it was some stuff that she had applied inwardly and outwardly to her throat, which had made her body swell. I made signs to her to begin and make some clothes for her child, at the same time showing her my infant, but she seemed to blow it away, making signs showing that she was not with child; I was in the habit of seeing Esther Dyson daily. On Friday last, the 24th ult., I saw her about twelve o’clock, at her own house-door, and she appeared quite big in the family way ; I did not see her again till about nine o’clock on Saturday morning, when she was washing the house-floor, and she seemed pale, languid, and weak. On Saturday morning last, about nine o’clock, I motioned her to know how she was; she then had a flannel tied round her neck. She motioned to that she had thrown up a large substance, and it had settled her body. About three o’clock on Sunday last, the 20th inst., I went to her house, and her brother motioned me that his sister was in bed very sick, but I did not go up stairs. About four o’clock on the same day, she appeared poorly and weak, and I desired her brother make her some tea, and I stopped till she took it. I left about five o’clock Sunday afternoon. From her altered appearance I have doubt she had been delivered of a child.

Hannah Butcher corroborated the above evidence, and said, that from her observation, as a married woman, she believed the prisoner had been delivered of a child on the Friday.

William Graham examined.- I am a blacksmith. I know the prisoner, and think her intelligent. On Saturday night last, 20th inst., at about 8 o’clock, I was returning home to Ecclesfield from Wortley, and I met the prisoner in Lee-lane, in Ecclesfield township, with something wrapped before her apron. She was on a footpath leading from Ecclesfield to Wortley and about 600 yards from the Cotton-mill Dam, where the body of female child has been found. She having passed, I met H. Woodhouse, and he asked me if it was not the dumb girl whom I had met ? and I said yes, it was.

Fanny Guest, a gentleman’s servant, who had been in conversation with Woodhouse, deposed to her having also seen the dumb girl pass her, with something under her apron.

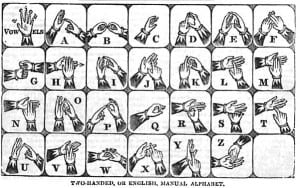

James Henderson, overlooker of the thread-mill belonging to Mr. Barlow, knows the prisoner and her brother, who is also deaf and dumb. They have worked in the mill 11 years. Is satisfied that the dumb girl is capable of distinguishing right from wrong. On Sunday last witness went to Wm. Dyson, the dumb man’s house, and he willingly gave me his keys to examine the boxes belonging to him. I saw nothing suspicious in his room. I then examined the prisoner’s room, and I found blood on the chamber floor, and blood partially wiped off the floor. The wall was also sprinkled with blood. I withdrew the curtain of her chamber window, and observed marks of blood on the window bottom. I opened a hand-box, and found two aprons and a skirt, on which appeared as if a substance had been laid upon them, the blood having run through the skirt. The prisoner came up stairs, and, by signs, desired me to come away, and not search. Being convinced that something wrong had been done, I sent for the vestry clark, and in his presence searched the prisoner’s box, and found several articles, from which it was evident that they belonged to person who had been delivered of a child. On Monday last, about an hour after the child had been found in the dam, it was brought to the Ecclesfield workhouse, and laid down she blamed him? She then satisfied me that he had no-thing to do with it, but that she had done it herself .She told her brother in my presence that she did not throw the child into the dam. She merely laid it in. I conceive the prisoner to be a shrewd, clever woman.Ann Briggs examined – I am the wife of Thomas Briggs, cutler of Ecclesfield. The piece of green cloth produced by Wm. Shaw, the constable, and in which the child was found, is part of a sofa cover belonging to Wm. Dyson, prisoner’s brother ; I took the body of the child out the cloth, and then to the workhouse ; I also, at the same time, took the head of the child also found in the dam, out of a separate piece of green cloth, which also belonged the sofa alluded to. I have practised as midwife for upwards of 20 years, and it is my opinion that the head of the child had been cut off by some dull instrument. Mr. Thomas Yeardley, who has a dumb child of his own gave me some books, which are published for the purpose of instructing deaf and dumb children; for up- wards of 12 months I instructed the prisoner in signs and learning her the dumb alphabet, and she obtained that instruction that I am convinced she can understand me ; she is of very quick apprehension. Monday last I went to the prisoner, and asked her to explain the manner to me how she was delivered of her child. I said to her, “The child’s head is cut off.” I have seen her several times since, and she still insists that the head came off. On reproving her with throwing it into the dam, she showed that she had, not thrown in it, but had laid it in pretty and nice.

James Machin deposed that, in consequence of information given him Sunday night, he went to the prisoner’s house, and found it in the state described by the other witnesses. I, assisted by W. Shaw, the constable of Ecclesfield, searched the dam, and pulled out the headless body of a fine full-grown infant – a female. This witness went on to corroborate the testimony of Henderson and Greaves, as to the appearance, in the prisoner’s bed-room.

Sarah Ingham deposed – l am the governess of the Ecclesfield workhouse. I went to the house of Dyson, and received from Henderson certain articles wrapped in bundle; they were saturated with blood. The articles produced are the same, and have been in my care ever since. I examined the breasts of the prisoner, and found a deal milk in them. She told the same story to the manner in which the head came off, she did the other witnesses. I produced a knife to her, and showed signs that she bad cut the head off. But she threw herself on one side, and shunned the idea.

Wm. Shaw, the constable of Ecclesfield, confirmed the testimony of Machin.

Mr. Wm. Jackson, lecturer on anatomy, stated that on the 27th day of September last he examined Esther Dyson the prisoner, and she had every appearance of having been recently delivered. He was decidedly of opinion, from the examination, that the head of the child had not been torn or screwed off by the mother. He had had no doubt, from the particular examination of the body of the deceased, and from the appearance that it exhibited on that examination, that the child was born alive.

Mr. Joseph Campbell, surgeon, having also examined both the woman and the child, fully corroborated Mr. Jackson’s testimony.

The coroner having summed up,

The jury retired, and in few minutes returned with verdict of Wilful Murder against Esther Dyson.

The coroner then issued a warrant for the unfortunate woman’s committal to York Castle, to take her trial the ensuing Lent Assizes. (London Evening Standard – Saturday, 2nd October, 1830)

It would be interesting to trace Yeardley’s child, and work out which book she or he was taught with – I would suggest Watson’s as used in the Old Kent Road Asylum. No one seems interested in who the father might have been – no doubt there was plenty of speculation locally. How much Esther knew of what society deems right and wrong, we can only guess.

Six months later, the case was decided in the Assizes.

FRIDAY, March 25. CHARGE OF MURDER.

ESTHER DYSON was this morning placed at the bar, charged with the wilful murder of her female bastard child, at Ecclesfield, near Rotherham, on the 24th of Sept, last.

In consequence of the prisoner labouring under the infirmity of having been born deaf and dumb, the greatest interest was excited, and the galleries were crowded on the opening of Court.The prisoner is 26 years of age, but does not appear so old. She is rather tall, and of slender make. She has light hair and complexion, and of rather a pleasing and pensive cast of feature. She was dressed in a coloured silk bonnet, a light calico printed dress, and a red cloth cloak. She had the appearance of a respectable female in the lower walks of life.

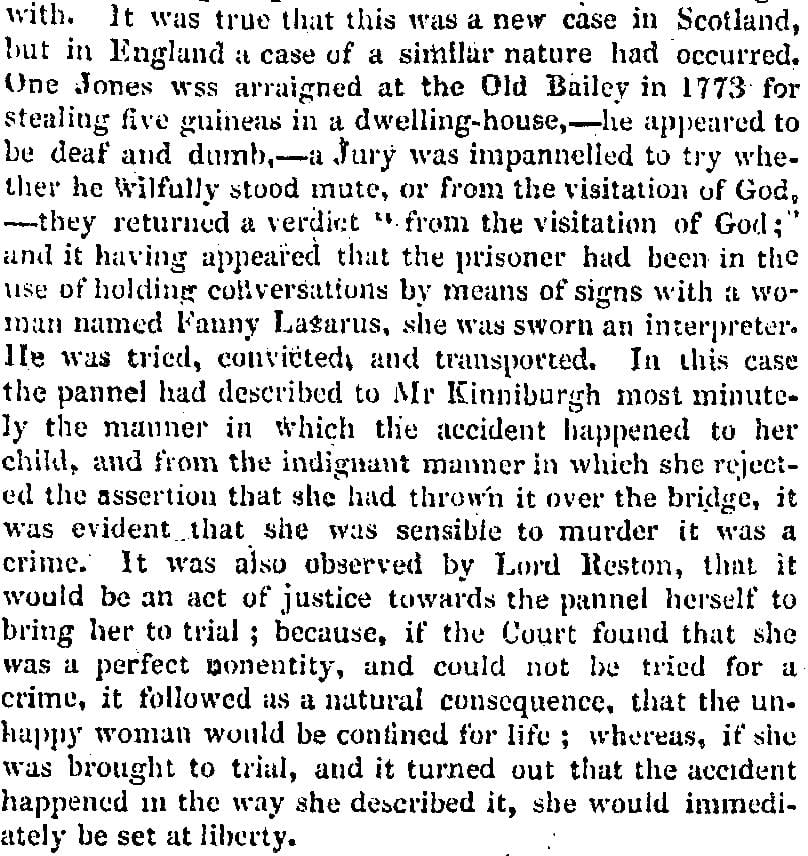

The Clerk of the Arraigns having read over the indictment, which contained four counts, in which the charge was differently stated, put the question, “Guilty or Not Guilty,” to which, in consequence of her infirmity, she made no answer.

The Jury was then impanelled, pro forma, to try whether she stood mute of malice, or from the act of God.

James Henderson was then sworn, who deposed that he communicate ideas to her by signs. He was then sworn to interpret the various questions to the prisoner.

In reply to a question from the judge, the witness stated In reply to a question from the judge, the witness stated that the prisoner had no counsel – that she had no father, mother or relative, except a brother, who was himself deaf and dumb.

His Lordship said she must have counsel, and at his request Sir Gregory Lewin undertook to conduct the defence. years, endeavoured to make the prisoner understand, by signs, that she might object to any of the gentlemen of the Jury, but he failed to make her comprehend the Jury, but he failed to make her comprehend the nature of the question.

The Jury returned a verdict “that the prisoner was not sane.”

The Judge then directed her to be remanded, and every proper means taken to instruct her. In a previous part of the proceedings, the Judge said he should reserve the point tor the consideration of the Judges, whether she should be tried upon the charge, or confined during the King’s pleasure. (York Herald – Saturday, 26th of March 1831)

Esther seems to have lived out her life in the asylum, dying in 1869, and was buried on the 23rd of March 1869, at the Parish of Stanley, York, England. William died, I think, in 1875.

We should recall that at this time you could be hanged for robbery and assault – that was the fate of three young men at the same assizes – Turner, Twibell and Priestley-

“Lord have mercy upon your souls.” During the passing of the sentence, Turner wept bitterly ; and, at the conclusion, exclaimed ” Oh, dear.” Twibell also sobs, and cried out – Oh, Lord spare our lives.” (ibid)

…so I think she was fortunate.

It really is not my intention to continually add lurid stories of death here, but that was life at the time. This tale is another one that points to the sad way many Deaf people in the past were unsupported, though it also shows that 19th century society was not without compassion, and how, despite their faults, the Institutions (schools and missions) could reduce this from happening as often, by giving children the ability to communicate and belong to a community.

Incidentally, Sir George Lewin came to an unfortunate end after getting into financial trouble.

Esther

1841 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 1271; Book: 10; Civil Parish: Wakefield; County: Yorkshire; Enumeration District: West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum Yorkshire; Folio: 51; Page: 16; Line: 10; GSU roll: 464241

England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 Class: HO 27; Piece: 42; Page: 403

England, Select Deaths and Burials, 1538-1991

https://ourcriminalancestors.org/the-story-of-esther-dyson/

‘Natural Pantomime’: Spectacle, Silence and Speech Disability Kate Mattacks

https://www.sheffieldhistory.co.uk/forums/topic/9047-infanticide-by-a-deaf-and-dumb-mother/

William

Deaths, 1875, March –

| DYSON | William | 71 | Wortley | 9c | 191 |

1871 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 2335; Folio: 241; Page: 21; GSU roll: 87581-87582

Yorkshire CCLXXXVIII.8 (Ecclesfield; Sheffield)

Surveyed: 1890, Published: 1892

Close

Close