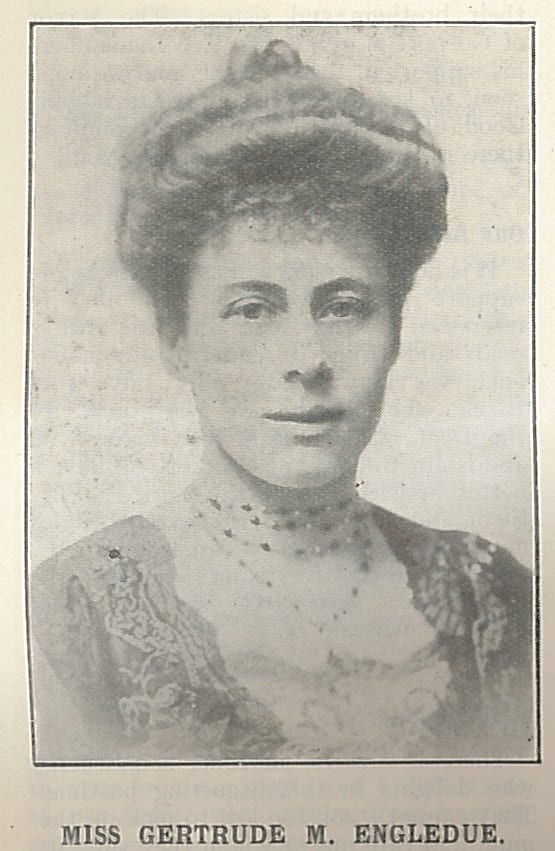

Gertrude M. Engledue and Edward Thomas – a deaf pupil and her teacher

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 4 August 2017

Gertrude Mary Engledue was born in Dublin, on the 30th of January, 1868, daughter of William John Engledue (born in Liverpool) and his wife Eliza McIvor Forrest (see www.ancestry.co.uk). Her parents married in India. She was deaf from birth, according to the 1881 census, and from childhood according to the 1901 census, but is not in the 1891 or 1911 censuses. In 1881 she was a pupil at a small school for deaf children in Bristol, run by Glamorgan born Edward Thomas, and his wife Emily, at 8 Burlington Buildings, Redland Park. Across the country there were thousands of these small schools, presumably not very well regulated, and run as small family businesses. Some, like this one, specialised in particular children, ones who needed more care. To what extent they got that, we might well question. Perhaps the surest guide would be to follow through as best as possible what became of those children in later life.  Here is a truncated version of the 1881 census –

Here is a truncated version of the 1881 census –

| Edward Thomas | Head | 37 | 1844 | Cowbridge Glamorgan | |

| Emily Thomas | Wife | 41 | 1840 | Bristol Gloucestershire | |

| Eliza Nurse | Mother in Law | 70 | 1811 | Bristol Gloucestershire | |

| Gertrude M. Engledue | Pupil | 13 | 1868 | Dublin | Deaf & Dumb birth |

| Isabella Shickle | Pupil | 12 | 1869 | Bath Somerset | Deaf & Dumb birth |

| John R.K. Toms | Pupil | 13 | 1868 | Wellington Somerset | Deaf & Dumb |

| Edward Foster A. | Pupil | 13 | 1868 | Canterbury Kent | Deaf & Dumb birth |

| Cyril G. Bosanquet | Pupil | 11 | 1870 | Ramsgate Kent | |

| Wilfred J. Reckitt | Pupil | 13 | 1868 | London Middlesex | Deaf & Dumb birth |

| Horace R McGrath. | Pupil | 8 | 1873 | Bempton Yorkshire | |

| Frederick J. Gourlay | Pupil | 10 | 1871 | Weston S M Somerset | Imbecile |

| Catherine Gourlay | Pupil | 8 | 1873 | Weston S M Somerset | Imbecile |

As we see, not all the pupils were deaf.

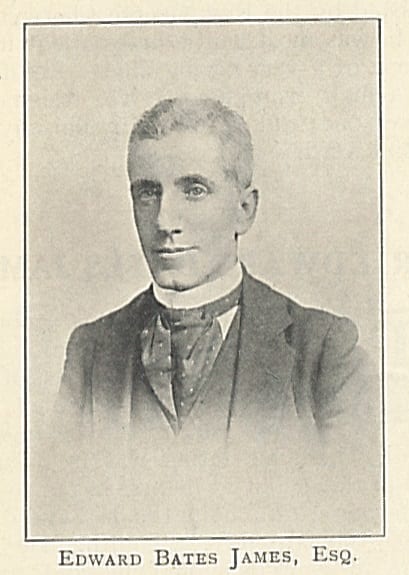

The teacher, Edward Thomas, became the missioner to the Deaf of Bristol in 1884, a post he held until his death in 1913. His first wife Emily died in early 1898. Within six months he had re-married, to Theodora Ryecroft, who was twenty years his junior. His obituary is full of praise for his hard work, visiting the sick and helping others to find work. We are told in his obituary that he “acted as interpreter when necessary at weddings, funerals, police court cases, etc.”

Within six months he had re-married, to Theodora Ryecroft, who was twenty years his junior. His obituary is full of praise for his hard work, visiting the sick and helping others to find work. We are told in his obituary that he “acted as interpreter when necessary at weddings, funerals, police court cases, etc.”

Gertrude later became President of the Portsmouth Deaf and Dumb Club. The brief notice in The Hampshire Deaf Chronicle for 1923 tells us that she travelled extensively abroad, and came “into contact with the deaf of many countries. She was the close friend of the late Sir Arthur Fairbairn, who during his life did so much for the Hampshire deaf.”

Well, she was in fact such a close friend that she married him, in February 1897. Sir Arthur Fairbairn had married Florence Frideswyde Long in 1882, but the marriage only lasted a couple of weeks (see Eagling and Dimmock for more on Fairbairn). Gilby says in his unpublished memoir,

it is quite often the case that a woman will marry a deaf man through pity, only to find out afterwards she has made a terrible mistake. So frequently have confidences of this nature been imparted to me and my wife that we feel bound to make known how unfortunate marriages of this sort are likely to prove. Sir Arthur Fairbairn made a marriage of this kind, and he was parted from his wife within a few weeks of the marriage. We are blaming neither of the parties to this marriage, but giving it as an instance. (Gilby memoir, p.66)

We might presume that although he was divorced, he felt unable to make his re-marriage public knowledge because of the social stigma.* Gertrude seems to have retained her maiden name, even unto death – her registration is as Engledue – and neither William Roe in his article on Fairbairn in Peeps into the Deaf World, nor Gilby in his memoirs, mention that he married Gertrude. Perhaps the couple’s friends kept the secret, but perhaps only a few people knew.

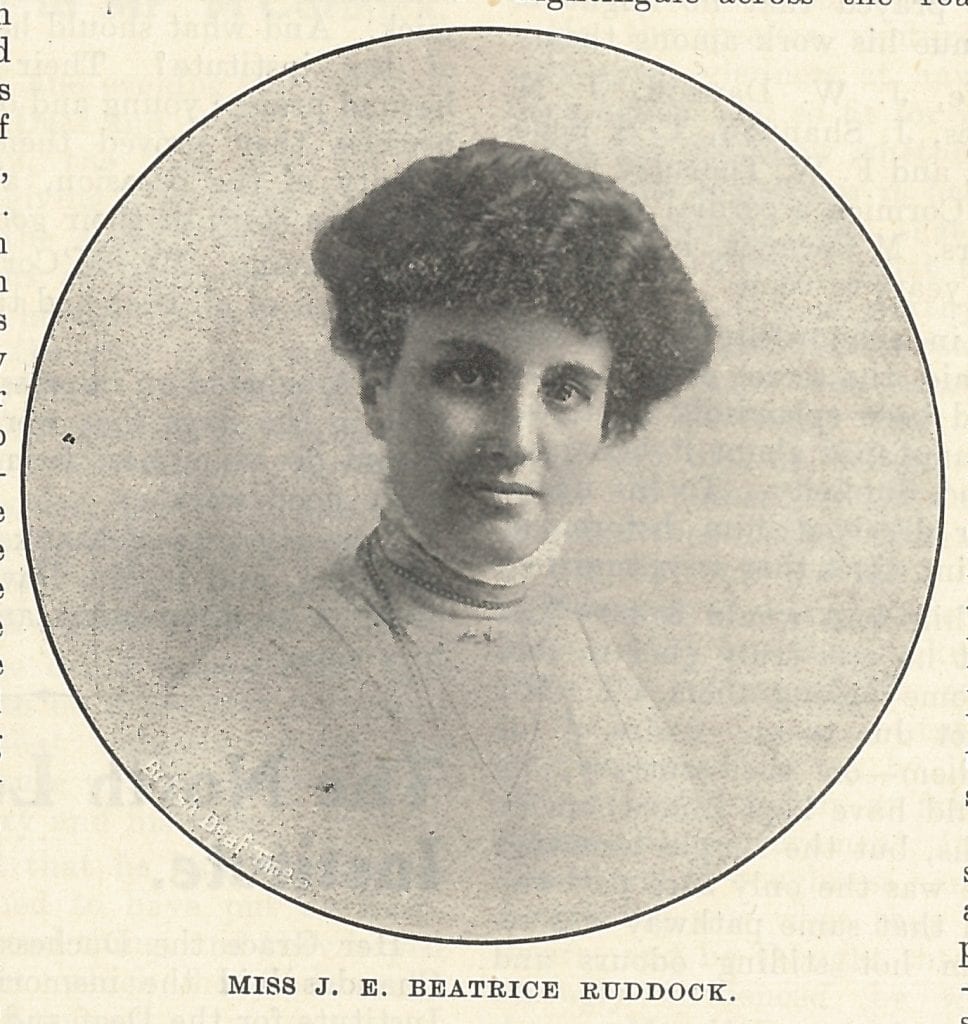

Gerty, as Gilby calls her at one point, was a close friend of Sir Arthur Fairbairn’s sister and companion, Constance. When, in 1904, the Royal Association for the Deaf and Dumb as it was then called, held a Grand Bazaar at Marylebone in the Wharncliffe Rooms of the Grand Central Hotel, Marylebone, Constance and Gerty were a great help. Constance,

had worked like a Trojan and with her great friend Miss Gerty Engledue, and those who helped at her stall did great things and died – yes died – a month after the event at which she lent her failing hands. […] Miss Gertrude Engledue (who had a deaf brother) and her Aunts were among our keenest supporters, and they were backing the Constance Fairbairn Stall. Indeed Miss Engledue and Miss Fairbairn were Hon. Secretaries with me. (Gilby p.178)

Gertrude died in Northiam, Sussex, on the 29th of April, 1952, and is buried in Tunbridge Wells.

How sad that they felt they could not live together.

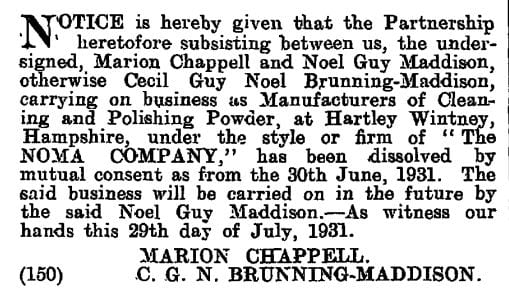

*I have not found a divorce record for them – if you have, please leave a comment below. Indeed, did they get divorced? Geoff Eagling and Arthur Dimmock say that the certificate for his second marriage in a registry office, calls him a bachelor. When Florence died in 1941 she was called lady Fairbairn, Sir Arthur’s widow in The Times. A Times story for 1909 reports the wedding of Thomas Fairbairn, arttended by Sir Arthur and ‘Mrs Fairbairn’ – is that Gertrude, as she is not called ‘Lady Fairbairn’?

[I found a death notice in the Times for 1944, placed by Gertrude to her faithful servant of 29 years, Catherine Barber, who was in 1911 a servant at the Fairbairn’s Chichester Home, Wren House.]

[Her Deaf brother would appear to have been James Allen, born in Calcutta – and a pupil at Bingham’s school, but I think this needs checking as the ancestry records say his father was William John, which might make him her uncle… It would then mean that Arthur may have been at school at the same time as James… This needs clarification! Gilby was a pretty reliable witness, and relied on old diary entries for the incomplete memoirs, but he was writing in 1938, and perhaps he was confused or forgot some details. Thanks to Norma McGilp @DeafHeritageUK for additional information.]

Woodford, W., Obituary Mr. Edward Thomas, British Deaf Times 1913, p.203

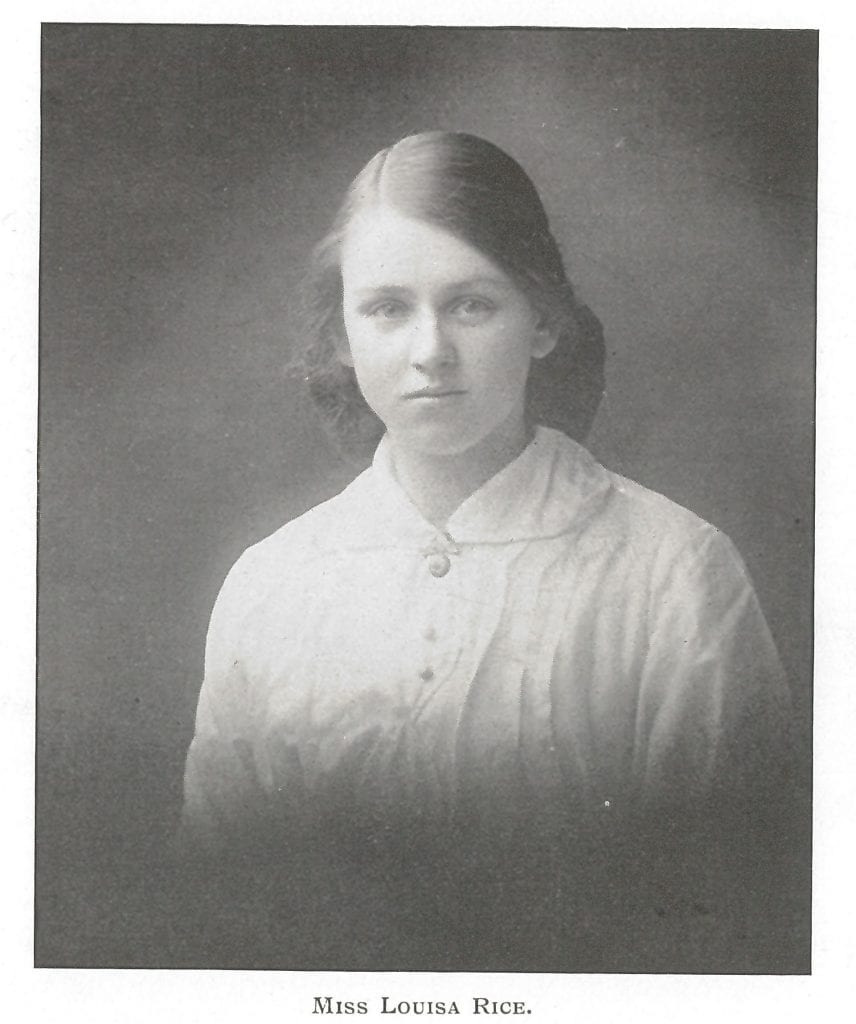

The Hampshire Deaf Chronicle. Jan-Feb-Mar 1924 p. 4 (Photo of Gertuude Engledue)

Eagling, Geoff, & Dimmock, Arthur, Sir Arthur Henderson Fairbairn, 2006

Gilby’s unpublished memoir

1861 Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 2212; Folio: 63; Page: 26; GSU roll: 542936

1881 Census – Thomas and Engledue – Class: RG11; Piece: 2503; Folio: 119; Page: 18; GSU roll: 1341604

1881 Census – Charles and Herbert Engledue – Class: RG11; Piece: 1231; Folio: 28; Page: 6; GSU roll: 1341301

1891 Census – Engledue – Class: RG12; Piece: 32; Folio: 71; Page: 25; GSU roll: 6095142

1901 Census – Thomas – Class: RG13; Piece: 2367; Folio: 186; Page: 30

1901 Census – Gertrude Engledue – Class: RG13; Piece: 36; Folio: 61; Page: 1

1901 Census – Ralph and Guy Engledue – Class: RG13; Piece: 593; Folio: 7; Page: 6

1911 Census – Engledue – Class: RG14; Piece: 133

Close

Close