Forgive the long nature of this blog post – I considered dividing it into three as it is the length of an essay, but in the end have left it as one, divided into three sections.

THE REIN FAMILY BUSINESS

Frederick Charles Rein was born in Leipzig, Saxony around 1812/13, a son of Frederick Charles Rein, who was described as a merchant on his son’s marriage record. 1813 was a momentous time in Saxony, which was the scene that October of the Battle of the Nations. Wagner was born in the city the same year. At some time around 1834/5 Rein moved to England, where he set up as an instrument maker. His naturalization papers in June 1855 (to be found on the National Archive*) say that he had been resident for over twenty years (but we may suppose less than twenty-one as otherwise he would have made that clear). Whether he undertook an apprenticeship as an instrument maker in Saxony or in London would be interesting to know. In December 1838, he was married in Whitechapel to Susanna(h) Payne of Wendover, whose father was a farmer or agricultural labourer (depending on the year of the census). At that date Rein was living in Gerrard Street, Soho, and described his job as merely ‘Instrument maker’. By 1851 Rein was an exhibitor and medallist at the Great Exhibition. In addition to the acoustic instruments – ear trumpets and variations on that theme – Rein also made a “Continual stream enema reservoir” and “several kinds of aperitive vases and enemas”. Perhaps these items share properties with the acoustic instruments. He also made ‘lactatory’ devices – breast pumps. These were advertised in contemporary newspapers, accessible via online databases.

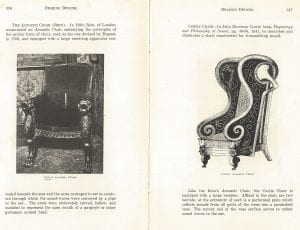

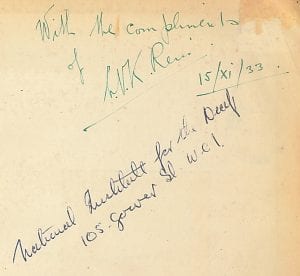

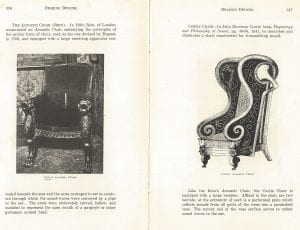

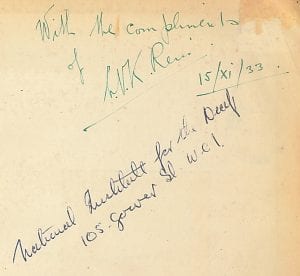

Berger’s The Hearing Aid: its Operation and Development (1970, p.7), says Rein began making non-electric hearing aids in London no later than 1800, a claim repeated by others in an internet meme, presumably on his authority. Max Goldstein’s book Problems of the Deaf (1933) has a picture of Rein’s ‘acoustic chair’ saying it was made in 1830. It is not called a ‘throne’. Our copy was donated to the library by Leslie V. K.-Rein in 1933 – of whom more anon. The claim is also usually repeated, without original evidence, that the ‘throne’ was made for King João VI of Portugal and Brazil (John VI in English) who was, we are told, deaf, or at least suffered from increasing hearing loss as he aged, and who died in 1826. Goldstein makes no mention of that. I cannot find any contemporary evidence in English that the king was deaf. There are many pages on the web that repeat the story, without solid proof. All the evidence I have found seems to come back to Berger.** It is unlikely that Rein made this ‘throne’ for João, unless Rein’s ‘merchant’ father was in fact an acoustic instrument maker who came to England. The chair was undoubtedly made by Rein, but later in the century, as a show piece. Goldstein has a picture of a speaking tube that he says was dated 1805 by ‘Rein & Son’, but this must be a misreading of the date which is most likely 1855 or 1865 by which time his son, Frederick Charles junior was working with him, as we can see from the name of the business in advertisements.

Berger’s The Hearing Aid: its Operation and Development (1970, p.7), says Rein began making non-electric hearing aids in London no later than 1800, a claim repeated by others in an internet meme, presumably on his authority. Max Goldstein’s book Problems of the Deaf (1933) has a picture of Rein’s ‘acoustic chair’ saying it was made in 1830. It is not called a ‘throne’. Our copy was donated to the library by Leslie V. K.-Rein in 1933 – of whom more anon. The claim is also usually repeated, without original evidence, that the ‘throne’ was made for King João VI of Portugal and Brazil (John VI in English) who was, we are told, deaf, or at least suffered from increasing hearing loss as he aged, and who died in 1826. Goldstein makes no mention of that. I cannot find any contemporary evidence in English that the king was deaf. There are many pages on the web that repeat the story, without solid proof. All the evidence I have found seems to come back to Berger.** It is unlikely that Rein made this ‘throne’ for João, unless Rein’s ‘merchant’ father was in fact an acoustic instrument maker who came to England. The chair was undoubtedly made by Rein, but later in the century, as a show piece. Goldstein has a picture of a speaking tube that he says was dated 1805 by ‘Rein & Son’, but this must be a misreading of the date which is most likely 1855 or 1865 by which time his son, Frederick Charles junior was working with him, as we can see from the name of the business in advertisements.

If Rein took over an existing business in the Strand, where the earliest record I can find of him is at 340 in 1841 on his son’s birth certificate for 22nd November, it may have been that of A.F. Hemming, an ‘elastical surgical instrument maker,’ who was at that address according to an advert in Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (Sunday 1st November, 1840).

Rein’s 1843 advertisement in The Age (Sunday, March 5th 1843, p.1; Issue 62) says that he was an “INVENTER [sic] and MAKER of the NEW ACOUSTIC INSTRUMENTS to H.R.H. the DUKE of SUSSEX, 340, STRAND, (nearly opposite Somerset House)”. (The Strand has been renumbered since Kinsgsway was built.) The Duke was Queen Victoria’s uncle. Unfortunately the Duke died a few weeks after this advertisement appeared. Rein quotes in full an encomium from Justice Patteson of 33, Bedford Square, dated June 21st, 1841, which means he must have been making and selling acoustic instruments by that date. I have however failed to find him in the June 1841 census, which is notorious for its poor transcription. In 1842, he was mentioned as an aurist, among other tradesman in the Strand, having a gas light, lit with the letters ‘P.W.’ to celebrate the christening of the Prince of Wales.

If there was a Rein making hearing devices before circa 1835 when Frederick came to London, I cannot find any reference to that. Why advertise making a device for a Royal Duke, rather than a king? If anyone can find evidence for any Rein in any acoustic related business in London before this, perhaps by referring to trade directories or rate books, please point this out in the space for comments.

One witness to Rein’s marriage was a James Aloys Muhlhauser. At first I could not find any record of him in the ancestry.co.uk databases, and I wondered if he left England before 1841. However I have since found a marriage record for him with Sophia Cronin, a widow, on 11/12/1837 at Saint Martin In The Fields. There is one possible Muhlhauser in the newspapers, who was one of the Germans who their fellow countryman J.H. Garnier appealed to the Lord Mayor on behalf of in 1836. They had moved to Switzerland and then were expelled as being rather too liberal in their political views, even though not directly involved in politics (see The Morning Post, Wednesday, August 24, 1836; Issue 20503). That Muhlhauser was living in Goodman’s Fields. This is a speculation – if it is the same Muhlhauser, is it possible that Rein knew him before he came to England – perhaps having resided in Switzerland as well? Note that Rein’s wife Susannah was resident in Wentworth Street, Aldgate, and they were married at St. Mary’s Whitechapel, which is not far from there. It would be interesting to see if the Rein family appears in any German archives.

The Victorian church of St. John the Baptist, Enderby, has part of the Rein pulpit speaking system surviving, according to Pevsner. It sounds like the device that Rein patented in 1867 in The Gazette. By the 1880s the shop was described as a Paradise for the Deaf (The Era, Saturday, July 9, 1887; Issue 2546). Rein’s work was clearly well regarded by otologists. In The Diseases of the Ear, their Nature, Diagnosis and Treatment (1868, p.417), Joseph Toynbee says, “The most useful of this class of instruments are the small cornets made by Mr. Rein, which are connected by a spring passing over the head, that serves to hold them in the ears”, while William Wilde in Practical Observations on Aural Surgery and the Nature and Treatment of Diseases of the Ear (1853, p.435) says, “Mr. Rein, an instrument-maker in the Strand, London, has given much attention to the subject, and made many improvements therein.”

SOME OTHER ACOUSTIC DEVICE BUSINESSES IN THE STRAND IN THE 1830/40s

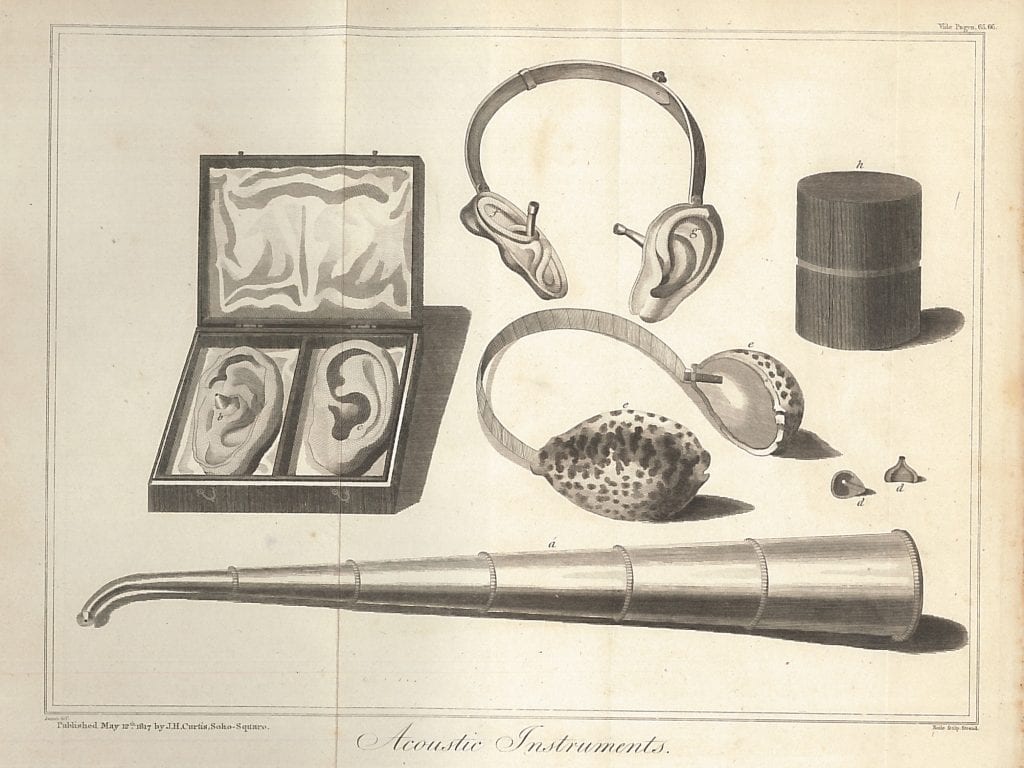

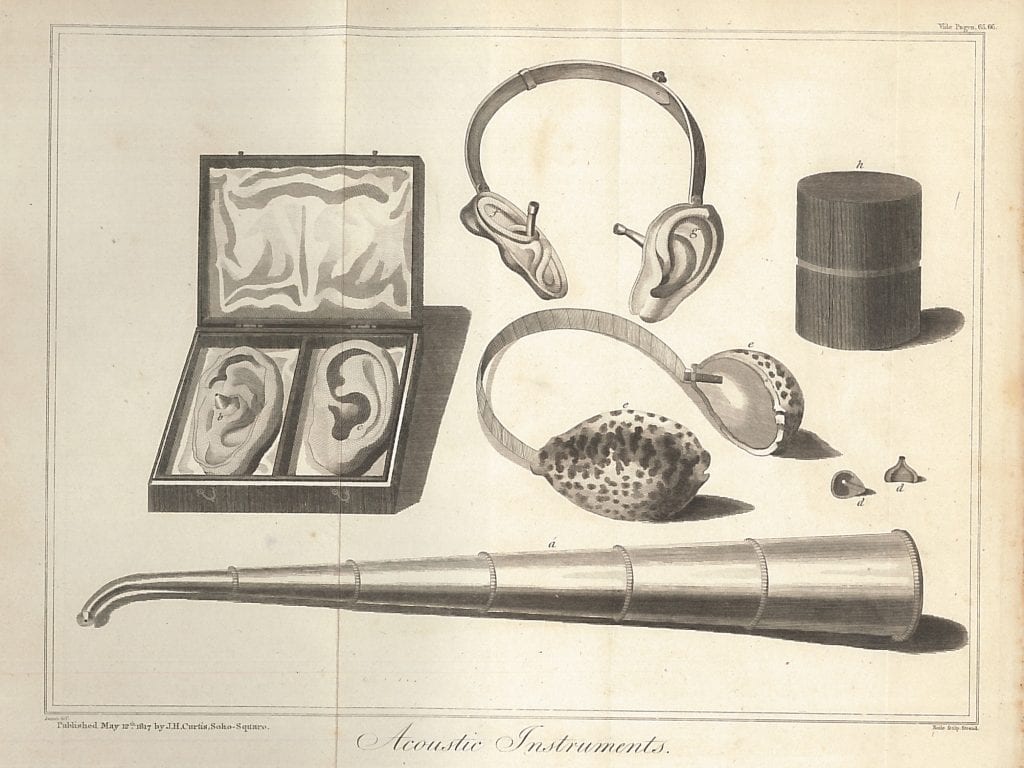

Aurist/surgeon John Harrison Curtis, regarded by Toynbee as a quack, was active through the early years of the century, and founder of the Royal Dispensary for the Diseases of the Ear, seems to have been influential in the design of acoustic instruments. He discusses the types available and some he designed in A Treatise on the Physiology and Pathology of the Ear (1817). The adjacent picture illustrates some of these. Curtis designed an acoustic chair in the early years of the century – see in the picture above to the right of the later Rein chair. The relevant section from the 5th edition of his book is here – A Treatise on the Ear 5th edition. According to the sixth edition of that book (1836, p.181), Curtis had his devices made by J. & S. Maw, of 11 Aldersgate Street.***

– see in the picture above to the right of the later Rein chair. The relevant section from the 5th edition of his book is here – A Treatise on the Ear 5th edition. According to the sixth edition of that book (1836, p.181), Curtis had his devices made by J. & S. Maw, of 11 Aldersgate Street.***

It appears that this chair inspired Rein to make his, though they are different in design. Curtis tells us that a model of his chair was on display in the National Gallery of Practical Science, Adelaide Street, Lowther Arcade which was in the Strand, along with his various hearing trumpets and artificial ears, and ‘a metal cast of the Internal Ear’ (A Treatise on the Physiology and Pathology of the Ear 6th edition, 1836). It seems likely that this display was influential on Rein and the other acoustic instrument makers in the Strand area.

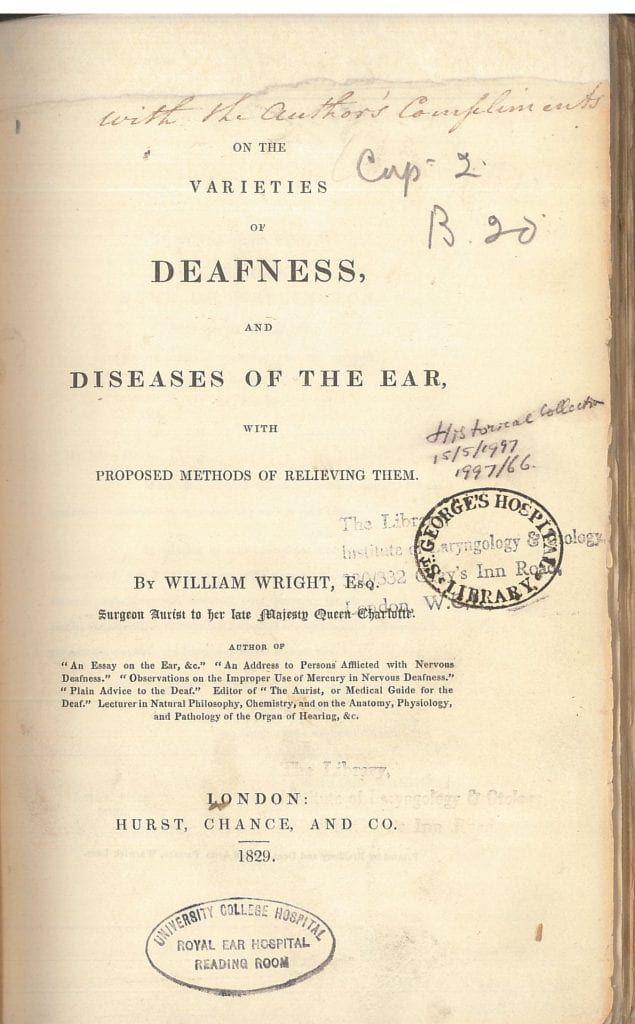

Other acoustic instrument makers (if that is not too specific a term for people who sold a variety of things, including ‘medical’ devices) of the late 1830s and 1840s, predating Rein, include the aurist William Wright, whose “Gong Metal Ear Trumpets” were manufactured and sold by L.H. Baugh at 199 The Strand, from at least 1832 to 1835. He wrote in On the Varieties of Deafness and Diseases of the Ear (1829, p.276), “the adaptation of an ivory ear-piece to a small bugle-horn, which I have directed to be made, appears to answer the purpose better than any other, and I believe the person to whom I gave the pattern, makes and sells a great number of them”.

To Persons Afflicted with Deafness. – L.H. Baugh, successor to S. Shepherd, 199, Strand, London, continues to manufacture the celebrated GONG METAL EAR TRUMPETS, and other ACOUSTIC INSTRUMENTS, so much approved of by the most eminent Surgeon-Aurists. These Instruments are universally admitted to be the most efficacious ever invented for the assistance of persons afflicted with deafness. The Trumpet is a handsome instrument, elegantly formed and finished, and may be carried in the pocket without the slightest inconvenience. Also the newly invented Ear Cap, which may be worn under a lady’s cap or bonnet without being perceived (The Morning Post, Monday, February 13, 1832; pg. [1]; Issue 19088).

Alfonso William Webster, who patented his otaphone in 1836 and was advertising it in the papers within weeks, available from 102 New Bond Street, then premises at 12 Chapel Street, Bedford Row, Holborn (The Standard, Thursday, April 07, 1836; pg. [1]; Issue 2781). He wrote A new and familiar treatise on the structure of the ear, and on deafness (1836) which we unfortunately do not have. He also wrote On the Principles of Sound; their application in the construction of public buildings, particularly to the New Houses of Parliament, etc (1840) , which is held in UCL Special Collections. The last date I can see for the ‘otophone’ [sic] being advertised is The Morning Chronicle, Wednesday, January 9, 1839; Issue 21573. It is possible this Alphonsus Webster was married to a lady called Ann and had at least one daughter, Eliza, born 1815, and a son Septimus, born 1830 (see the IGI). I cannot find Webster in the 1841 census. Perhaps he died around that time, which may explain why he no longer advertised.

S. & B. Solomons of Albemarle Street, “Opticians and Aurists to their Majesties the King and Queen of Hanover” – they add, “No connexion [sic] with persons of the same name” – and, a person of the same name, Mr E. Solomons of 36 Old Bond Street, “Optician, Patentee of the Amber Spectacles,” who “respectfully informs the public that he has effected a vast improvement in VOICE CONDUCTORS, for aiding and permanently relieving all CASES of DEAFNESS. They are acknowledged to be far superior to any hitherto offered, do not require to be held, and are formed on a scale so small as to be scarcely visible.” etc… (The Age, Sunday Oct 4th, 1838 p.320). Next to this advertisement is one for Dr James Scott‘s establishment at 369 The Strand, under his ‘superintendent’ William B. Pine, offering the Soniferon, a sort of table based ear trumpet that “stands on a pillar like a lamp,” and Dr Scott’s Ear Cornets, “invaluable to those individuals whose whose deafness does not require so powerful an instrument as large as Soniferon.” In 1836 Scott was not at that address it seems, from an advert in 1836, but that they were being manufactured under Scott’s supervision by Savory and Co., ‘chemists and medical instrument makers’ (Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, Sunday, October 30, 1836). That changed to ‘Scott and Co.’ in March 1837, or ‘Scott, Savory and Co.’ in some adverts, and not long after they must have dissolved their arrangement. Savory had other premises in New Bond Street. In 1837 Scott was advertising ‘Voice Conductors’ (The Age, Sunday, May 28, 1837; pg. 176).

Scott was born in 1789 in Calne, Wiltshire. He may have been from relatively humble origins but I have not traced his whole career: there is probably more to discover. He certainly married before 1819 when his daughter Emmaline or Emmeline was born. In 1822, he was a supposed inventor of a stomach pump. It seems to have caused some controversy in The Lancet (p.52, 1824). His double action bidet pump, lavement, cornets and soniferon can be seen in A companion to the medicine chest, and compendium of domestic medicine (1840) by John Savory – see the picture above. His son Montagu Scott was a solicitor and his son was Percy Montagu Scott, a naval gunnery expert, who was a student at UCL. Whether there is a connection there with his grandfather’s pumps we may never know.

William Blackmore Pine was born on the 4th of August 1812 in Tovil near Maidstone. He was the son of John Pine and his wife Rebecca, nee Carberry. His parents were non-conformists, his birth being registered as such in London in 1829. In 1844 he married an Irish girl, Louisa Hawkins, in Lambeth. He was the front for Scott’s business for many years but eventually he emigrated to Australia. Pine designed a hearing instrument himself, with this rather attractive flower cornet from 1849. One page in The Times (Tuesday, Jul 02, 1850; pg. 11; Issue 20530), has adverts for Pine’s cornet, Rein’s auricles, and S. and B. Solomons’s “organic vibrator an extraordinarily powerful, small, newly invented instrument for deafness, entirely different from all others, to surpass anything of the kind that has been, or probably ever can be, produced” (ibid).

From “the Quack Doctor” pages by medical historian Caroline Rance, I discovered Scott had an embarrassing and tragic episode when a boy was fished out of the Thames at Waterloo Bridge and brought to his house. He said to them, “Be off with you – take it to Charing Cross Hospital” (Medical Times, July, 1844, p.308-9). “It” – the boy – died. Scott declined to appear at the inquest, sending a ‘medical man’ Mr. Pine. As you will see, the Medical Times questioned Scott’s medical background, asking “Who is Dr Scott? He is no member of the London College”. It can be no coincidence that not long afterwards, the letter appeared from Heidelberg, assuring British readers that they were a genuine medical school, though that some were purporting to have degrees from them when that was not true. These clippings from The Medical Times of August the 20th, 1844, p.391-2, illustrate the problem of guaranteeing that a medical degree was genuine. Scott had obtained his from Heidelberg in 1833. Obtaining a place in a British Medical School may not have been easy without the ‘right’ background, so perhaps studying abroad was a serious option for clever students with little family wealth. There were a number of James Scotts around in the 1840s in central London, but it seems that our Scott is one and the same. He seems to have known John Snow, of Cholera fame, and to have hosted a medical meeting of the Westminster Medical Society at his premises, on least on one occasion.

From “the Quack Doctor” pages by medical historian Caroline Rance, I discovered Scott had an embarrassing and tragic episode when a boy was fished out of the Thames at Waterloo Bridge and brought to his house. He said to them, “Be off with you – take it to Charing Cross Hospital” (Medical Times, July, 1844, p.308-9). “It” – the boy – died. Scott declined to appear at the inquest, sending a ‘medical man’ Mr. Pine. As you will see, the Medical Times questioned Scott’s medical background, asking “Who is Dr Scott? He is no member of the London College”. It can be no coincidence that not long afterwards, the letter appeared from Heidelberg, assuring British readers that they were a genuine medical school, though that some were purporting to have degrees from them when that was not true. These clippings from The Medical Times of August the 20th, 1844, p.391-2, illustrate the problem of guaranteeing that a medical degree was genuine. Scott had obtained his from Heidelberg in 1833. Obtaining a place in a British Medical School may not have been easy without the ‘right’ background, so perhaps studying abroad was a serious option for clever students with little family wealth. There were a number of James Scotts around in the 1840s in central London, but it seems that our Scott is one and the same. He seems to have known John Snow, of Cholera fame, and to have hosted a medical meeting of the Westminster Medical Society at his premises, on least on one occasion.

A FAMILY TRAGEDY

Rein continued his business until his death in 1896, employing a brother-in-law Michael Payne, and later a nephew Cornelius Payne. Rein’s son, the third Frederick Charles, does not seem to have been terribly happy. He married Mary Aleyna Winter in 1867, but of their two children, the first girl died aged two, and the second Nelly Maud (or Nellie Maud) never married. He seems to have used the name Charles. There are two unfortunate stories to be found about him, which point the way to his end. The first is from April 1893:

FROM THE DOCK TO THE JURY BOX

Frederick Charles Rein, living in the Strand, was charged with being drunk and disorderly. The case was last on the list, but it was heard first as the prisoner was anxious to get away, he being one of the jurymen engaged at the Law Courts. – Police-Constable 461 E stated that at 7 o’clock on Thursday evening prisoner was having an altercation with a match boy in the Strand. He was very drunk, made a great noise, and refused to go away. Prisoner denied being drunk, but said he was excited owing to a dispute with his father. – He was fined ten shillings (Daily News, Saturday, April 22, 1893; Issue 14682).

A second incident occurred in December 1894. Under what the The Dundee Courier & Argus uncharitably calls A CHRISTMASTIDE PHILANTHROPIST, but The Standard just WESTMINSTER, the following appears:

Frederick Carden, 54, describing himself as a carriage trimmer and refusing his address, was charged with robbing Mr. Frederick Rein at the Victoria Station of the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway. – Prosecutor resides at Landwednock, Sutton, in the County of Surrey. His recollection of what occurred was of a rather hazy description, but said that he had some notion whilst sitting on the railway station platform that the Prisoner, professing to be a “well-disposed person who would see him home,” gave him a quantity of rum, which he (Mr. Rein) was fool enough to drink. – The story from this point was continued by Detective-sergeant Osborn, who noticed the couple on the seat together, and doubted the philanthropic intention of the Prisoner. Concealed in a railway brake the detective watched and saw the Prisoner make three attempts to get the Prosecutor’s umbrella from between his knees, which were crossed. Failing to pull it away, Prisoner undid the Prosecutor’s waistcoat and took out his gold watch, which he failed to easily detach. Mr. Rein seemed to rouse himself a bit during this operation, but the Prisoner gave him some more rum after himself pretending to drink. With the last lot of spirits Prosecutor seemed quite overcome. Prisoner lent [sic] over him and was clearing his pockets when Witness rushed out and seized him. Mr. Rein’s gloves were at the time in the Prisoner’s trouser pockets. – The Detective’s evidence was corroborated to a large extent by a telegraph clerk, and Osborn said that a remand would enable other witnesses to attend. – Prisoner said it was all a mistake through a good-natured act. He got acquainted with the Prosecutor early in the evening in the Strand and being Christmas time accepted his invitation to have a drink. Mr. Rein also treated a boot black. Prosecutor asked him (Prisoner) to see him safe home, and after various stoppages they got to Victoria. On the way the gentleman gave money to policemen for treats, and at Victoria he was very liberal with refreshment to the officials. He (Prisoner) during the whole evening carried Mr. Rein’s parcel and his gloves. After a long sleep in the lavatory, which resulted in the loss of his train, Prosecutor sat down on one of the station seats, and rum was brought to him because he complained of feeling chilly. – Mr. De Rutzen remanded the Prisoner in custody (The Standard, Tuesday, December 25, 1894; pg. 6; Issue 21990).

One can only imagine the conflict between father and son. Frederick senior died on 1st March 1896 of diabetes, senile decay, and exhaustion, his nephew Cornelius being present. His wife inherited £814 9d net. She probably sold the business fairly soon, to the Optician who worked in the shop next door, Charles Kahn. Frederick junior retired, but died on 20th April, 1900 in Wendover, home of the Payne family, of “chronic Alcoholism, 2 years, influenza and bronchitis, 21 days”. He cannot have left his wife and daughter with much, for in 1911 they were living in Newton Abbott, Devon, working as respectively a dressmaker and a daily governess.

Kahn kept the trading name of F.C. Rein and Son, and curiously, his son Leslie Victor Kahn was eventually to adopt the surname Rein himself. He was clearly technically adept, learning about electronics and writing a letter to Wireless World in 1932 (p.525-6), that is an appeal for what we would now call professional audiologists, and saying that he had then ten years experience working with audiometers and had invented two. He died in 1956, and in 1963 or thereabouts, the business was, we are told in various books, taken over by Amplivox. It was only under Kahn that the claim that Rein was ‘est. 1800’ first appears in adverts, based on what evidence, if any, we cannot say. I suspect that Leslie Kahn Rein passed that on to Goldstein on one of the trips to America that the Kahn family website mentions in the link above.

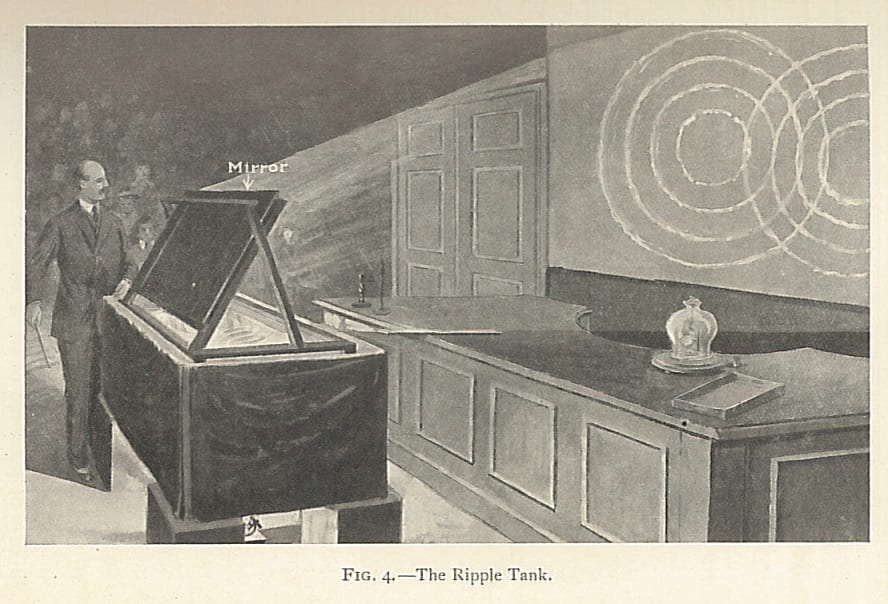

Here is a picture from The New Acoustics by N.W. McLachlan, OUP 1936, and it was published courtesy of Captain L.V.K. Rein, who we might suppose is the gentleman. Note that his subject or customer is seated in the acoustic chair.

I try to support claims as far as possible, but please point out any errors you find. Where people make unsupported claims, or claims with secondary evidence or non-contemporary evidence, be a little sceptical. Never take it as read – check the sources of claims, particularly if they seem implausible. This blog grew far beyond what I had intended, and much was written and researched in my own time. It is not intended as a ‘finished’ history, rather as a stimulus to others to discover more.

REIN family

Whitechapel Parish Records – London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: P93/MRY1/040

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:1:MP5KY5G

1851 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 1511; Folio: 184; Page: 1; GSU roll: 87845

1861 Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 861; Folio: 32; Page: 18; GSU roll: 542712

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 334; Folio: 87; Page: 1; GSU roll: 1341072

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 544; Folio: 108; Page: 64; GSU roll: 6095654

The Times (London, England), Wednesday, Jan 26, 1842; pg. 3; Issue 17890 [accessed 11/4/2018]

Other references

Berger, Kenneth W., The Hearing Aid (1970)

John Bull (London, England), Saturday, May 22, 1841; pg. 243; Issue 1,067.

Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (London, England), Sunday, October 30, 1836.

Goldstein, Max, Problems of the Deaf (1933)

Neil Weir, ‘Curtis, John Harrison (1778–1860)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2007 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/57673, accessed 8 Nov 2016]

Weir, Neil, and Mudry, Albert, Otorhinolaryngology: An Illustrated History, 2013.

The references were supplemented by G.R.O. certificates for Rein family members, and wills from the probate archive online, as well as searches of online newspapers and the ancestry.co.uk website.

*Many thanks, as ever, to Norma McGilp of @DeafHeritage for pointing me towards the naturalization papers. Rein’s naturalization papers are supported by four people. One, Edward Henry Rudderforth was a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. There are almost no details of him in Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows. He was involved in the extraordinary life of Mrs Weldon. Another was George Huntly Gordon, who worked for the Stationery Office.

**I have asked Brazilian audiologist friends if they can find anything on King John VI and will update if there is contemporary evidence forthcoming. Even if we suppose Rein’s father made acoustic instruments, for which we have no evidence, his son, our Frederick, was born in Saxony in 1813, so his father would have to have returned there, had a family that lived apart from him, returned to London, made the throne, and his son only to have joined him in England as an adult, then not had a company name as Rein & Son until decades later.

*** See more on Maw (!) here- http://collectionsonline.nmsi.ac.uk/detail.php?type=related&kv=105380&t=people

[Minor edits 22/2/17, line added 11/4/2018, Picture of Rein added 9/8/2018]

[More added on Muhlhauser 12/10/2018]

[Minor edit 19/11/2019]

William Cheselden (1688-1753) has been called “one of the most brilliant operators whose achievements are on record” (DNB 1921-2, p. 192). He was born in Burrough-on-the-Hill (but in the parish of Somerby), Leicestershire, and trained under William Cowper (1666-1709), an anatomist who was involved in an early plagiarism scandal.

William Cheselden (1688-1753) has been called “one of the most brilliant operators whose achievements are on record” (DNB 1921-2, p. 192). He was born in Burrough-on-the-Hill (but in the parish of Somerby), Leicestershire, and trained under William Cowper (1666-1709), an anatomist who was involved in an early plagiarism scandal. Close

Close