Brunswick House Hostel, “for Deaf and Dumb Girls who have no homes and are lonely in their affliction”

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 31 October 2014

In 1919 the Brunswick House Hostel for Deaf and Dumb Girls was founded at 19, Beaulieu Villas, Manor Gate, Finsbury park in North London. It seems that a moving spirit behind the foundation was Mrs Herbert Jones, who was I believe the wife of the Rev. Vernon Jones, Chaplain to the Deaf in North London. It aimed “to provide a safe and comfortable home for deaf and dumb girls who are alone in the world, or whose relations are unable, or unwilling, to look after them.” (Annual Report 1929, p.1)

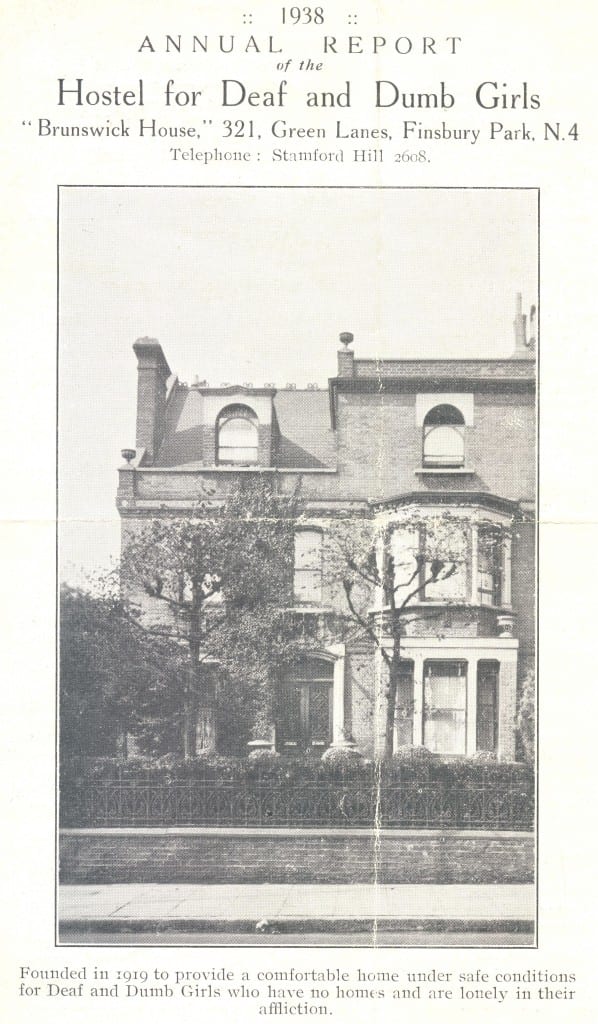

In August 1930 they were given six weeks notice to leave Beaulieu Villas as they were required by “the Electric Railway Company, in connection with the new Tube Railway Station that will be built at Manor Gate, Finsbury Park” (Annual Report, 1930 p.3), but they were fortunate to find a house opposite the St. John of Beverley centre in Green Lanes (see image below). The house is still there.

Here is one of the worthy patronesses, Lady Barrett, Chairman of the hostel, who was “Called Home” in 1930. Other founding members were Lady Maxwell Lyte, Lady Baddeley (wife of a Lord Mayor of London), Mrs. Edmondson, Mrs. Firminger, Mrs. H.R. Oxley (I am not clear if this was a relative of Selwyn Oxley), Mrs. A. J. Wilson (see earlier entries for her husband), Mrs. Wise, Mrs. Hankey and Mrs. Woods.

Here is one of the worthy patronesses, Lady Barrett, Chairman of the hostel, who was “Called Home” in 1930. Other founding members were Lady Maxwell Lyte, Lady Baddeley (wife of a Lord Mayor of London), Mrs. Edmondson, Mrs. Firminger, Mrs. H.R. Oxley (I am not clear if this was a relative of Selwyn Oxley), Mrs. A. J. Wilson (see earlier entries for her husband), Mrs. Wise, Mrs. Hankey and Mrs. Woods.

I do not wish to belittle the efforts of these people, but for some of them at least it was clearly one of those cases when those with wealth found charitable work that sat comfortably with their weltanschauung.*

When the home closed we do not know, but I suspect that the war may have meant they were evacuated, and the improved social welfare of the post-war years saw many changes to these small charities, with closures or state institutions taking over.

Annual Reports, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1933, 1938

Annual Reports, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1933, 1938

Update 5/11/2014: Thanks to @DeafHeritageUK for pointing out that we have a couple of photos of the hostel prior to the move, including this one with Selwyn Oxley enjoying tea with the ladies, probably in the early 1920s and around March or April from the daffodils on the table.

Close

Close