IRDR Masters student publishes Early Warning and Temporary Housing Research. This is part of the on-going collaboration between UCL-IRDR and IRIDeS-Tohoku University

By Joanna P Faure Walker, on 4 June 2018

Angus Naylor, an IRDR Masters student alumni and Masters Prize Winner, has published the research conducted for his Independent Research Project. The research was carried out as part of his MSc Risk, Disaster and Resilience with me, his project supervisor, and our collaborator at Tohoku University IRIDeS (International Research Institute of Disaster Science), Dr Anawat Suppasri.

Following the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011, UCL-IRDR and Tohoku University IRIDeS wanted to join forces to learn more about both the fundamental science and impacts of disasters both in Japan and around the world. Naylor’s recently published paper adds to other collaborative outputs from the two institutes: Mildon et al., 2016, investigating Coulomb Stress Transfer within the area of earthquake hazard research; Suppasri et al., 2016 investigating fatality ratios following the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami; and IRDR Special Report 2014-01 on the destruction from Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines. The two institutions have met on a number of occasions, and have an upcoming symposium in October 2018.

In 2014, three and half years after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami destroyed much of Tohoku’s coastline, I led and Dr Anawat Suppasri organised a joint UCL-IRDR and Tohoku University IRIDeS team, visiting residents of six temporary housing complexes in Miyagi and Iwate prefectures. While there, we used written questionnaires and informal group interviews to investigate the suitability of early warning systems and the temporary housing among the elderly population affected by this event.

When analysing the results, we found overall that age was not the principal factor in affecting whether a warning was received, but did play a significant role regarding what was known before the warning was received, whether action was taken and how temporary and permanent housing was viewed. The results suggest that although the majority of respondents received some form of warning (81%), no one method of warning reached more than 45% of them, demonstrating the need for multiple forms of early warning system alerts. Furthermore, only half the respondents had prior knowledge of evacuation plans with few attending evacuation drills and there was a general lack of knowledge regarding shelter plans following a disaster. Regarding shelter, it seems that the “lessons learned” from the 1995 Kobe Earthquake were perhaps not so learnt, but rather many of the concerns raised among the elderly in temporary housing echoed the complaints from 16 years earlier: solitary living, too small, not enough heating or sound insulation and a lack of privacy.

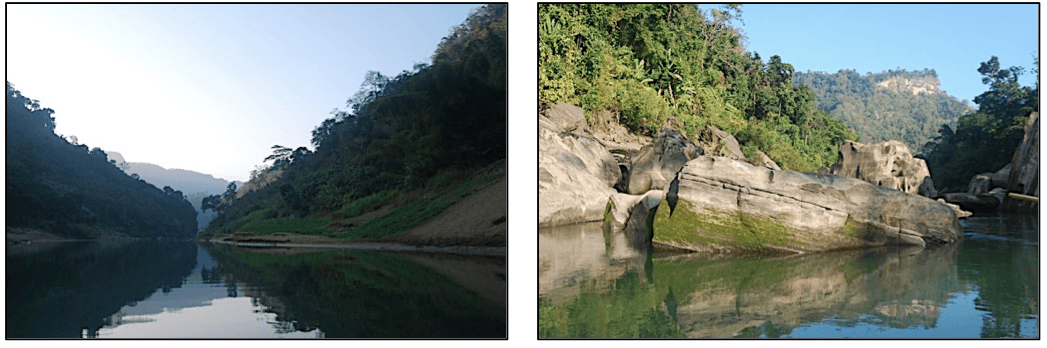

An example of Temporary Housing following the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami visited during the fieldwork for this study (Photograph: Dr Joanna Faure Walker)

The research supports previous assertions that disasters can increase the relative vulnerabilities of those already amongst the most vulnerable in society. This highlights that in order to increase resilience against future disasters, we need to consider the elderly and other vulnerable groups within the entire Early Warning System process from education to evacuation and for temporary housing in the transitional phase of recovery.

The paper, ‘Suitability of the early warning systems and temporary housing for the elderly population in the immediacy and transitional recovery phase of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami’ published in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, can be accessed for free until 26th July here, after this date please click here for standard access.

The authors are grateful for the fieldwork funds which came from The Great British Sasakawa Foundation funding to UCL-IRDR and MEXT’s funding to IRIDeS. The joint UCL-IRDR1 and IRIDeS2 fieldwork team comprised Joanna Faure Walker1, Anawat Suppasri2, David Alexander1, Sebastian Penmellen Boret2, Peter Sammonds1, Rosanna Smith1, and Carine Yi2.

Angus Naylor is currently doing a PhD at Leeds University

Dr Joanna Faure Walker is a Senior Lecturer at UCL IRDR

Dr Anawat Suppasri is an Associate Professor at IRIDeS-Tohoku University

Close

Close