The row over Home Office vans telling illegal immigrants to “go home or face arrest” has once more put immigration in the spotlight. In the run up to the 2015 general election, the Tories will undoubtedly come up with more initiatives to show they are serious about curbing immigration and to take the wind out of UKIP’s sails.

They have every reason to be concerned about immigration dominating the campaign. Public opinion on the issue has become more restrictive in recent years. For instance, 75% of respondents to the 2012 British Social Attitudes Survey wanted a reduction in immigration while only 63% felt the same in 1995.

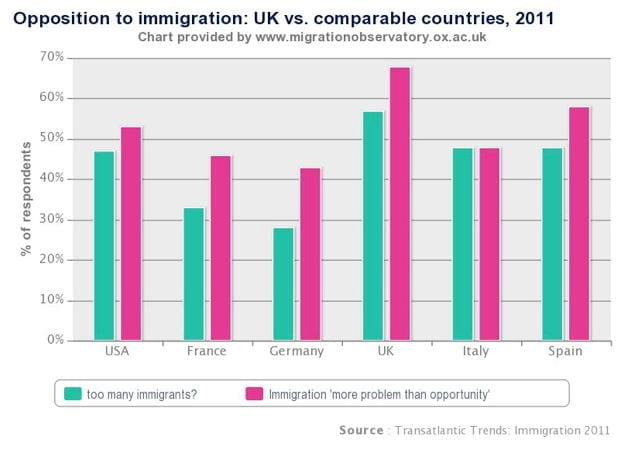

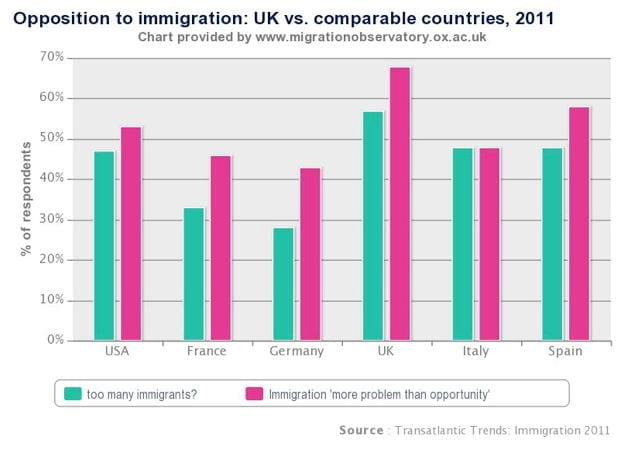

People also have more negative expectations. In 2002 just 43% thought that immigration would have negative economic effects and only 33% believed it had negative cultural effects. By 2012 these percentages had risen to 52% and 48% respectively. So it may not be surprising that there is also more opposition to immigration in the UK than in comparable countries. The UK has not only the highest number of respondents saying that there are too many immigrants (58%), but also the highest number believing that immigration presents more of a problem than an opportunity (68%) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

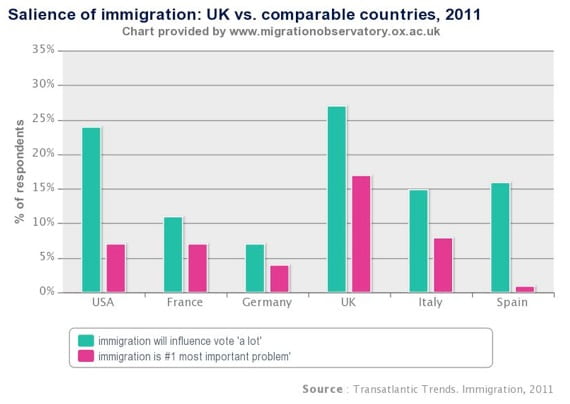

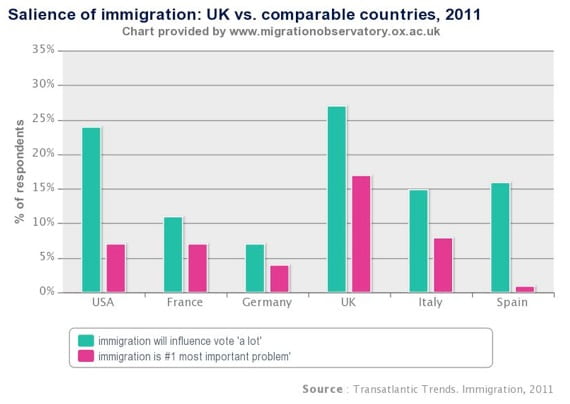

These attitudes would not matter too much if people did not see immigration as an important issue – but they do. More people in Britain than in comparable countries say immigration will influence their vote “a lot” (27%) and as many as 17% think it is “the most important problem” (see Figure 2). It is an issue no party can afford to ignore.

Figure 2

Negative attitudes on immigration always spark concern among scholars and policy makers because they are seen as a symptom of a much wider complex of exclusionary and racist attitudes to minority ethnic groups as a whole, including people born in Britain.

If this assumption is correct, there is certainly reason for apprehension. The key question is whether anti-immigration attitudes reflect intolerance more generally. Data collected in 2011-12 by LLAKES researchers among more than 500 14 to 20-year-olds in greater London provide some preliminary answers. We can see that young people’s attitudes on immigrants mirror those of the adult population (see Table 1). There are, for instance, slightly more people who agree that immigrants increase crime rates than those who disagree. Likewise, considerably more people agree that immigrants take jobs away from the native population than disagree. The number agreeing that immigrants are good for the UK’s economy is also smaller than the number disagreeing.

Yet, these rather unfavourable attitudes appear not be indicative of racially intolerant and exclusionary views more generally. Overwhelming majorities agree with the idea of equal opportunities in employment and education for all ethnic groups. Similarly, almost nobody objects to mixed race marriage or to having people of a different race as neighbours or colleagues. These figures would lead one to think that anti-immigrant attitudes are not necessarily part of a wider syndrome of intolerance and ethnocentrism.

Table 1. Attitudes on immigrants, race and ethnic groups

|

%disagree and strongly disagree |

% agree and strongly agree |

| Immigrants are generally good for the UK’s economy |

33.1 |

29.9 |

| Immigrants take jobs away from people who were born in the UK |

26.2 |

52.2 |

| Immigrants increase crime rates |

33.8 |

34.7 |

| All ethnic groups should have equal chances to get good jobs in this country |

74.9 |

| All ethnic groups should have equal chances to get a good education in the UK |

81.2 |

| Mixed race marriage is ok |

86.1 |

| I wouldn’t mind working with people from other races |

88.8 |

| I wouldn’t mind if a family of a different race moved next door |

84.1 |

Unfortunately, this is a premature conclusion. We also need to study correlations between unfavourable views on immigrants and wider exclusionary attitudes. Analysis of these correlations shows that there are, in fact, strong relationships between these sets of attitudes and that they are all in the expected direction. All but two of the fifteen correlations between the three questions on immigrants and the five questions on racial tolerance and ethnocentrism are significant at the .001 level, indicating very strong relationships (these results can be obtained from the author upon request). Reliability analysis, moreover, shows that all these attitudes are so well correlated that they form one coherent complex of attitudes (with an alpha value of 0.84), a complex we may label as “ethnic tolerance”.

So, although levels of racial intolerance and ethnocentrism are low in comparison to unfavourable attitudes towards immigrants, the latter do appear to be strongly related to the former. Their interconnectedness means that politicians and opinion-makers have to act responsibly in discussing immigration. Any unfounded negative statements on immigrants and immigration may not only make people more negatively disposed towards immigrants but also fan the flames of ethnic hatred in general.

Close

Close