Bullying: What have longitudinal studies taught us?

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 17 November 2015

Meghan Rainsberry.

The Department for Education (DfE) announced yesterday that 30,000 fewer children in England are experiencing bullying today compared to 10 years ago. This is a welcome finding as anti-bullying charities, schools, local authorities and others gear up for this year’s Anti-Bullying Week (16-20 November).

But other evidence suggests that the problem persists for many minority groups, and that the scarring effects of childhood bullying last well into adult life.

Longitudinal studies follow people throughout their lives, collecting information on their health, wellbeing, education, employment, family life and social networks. They are a unique resource for understanding who is at risk of being bullied, and what long-term effects bullying can have on our lives.

Bullying and minority groups

Everyone gets bullied at some point in life – is this really the case, or are some at greater risk than others?

Findings from Next Steps and the Millennium Cohort Study, following young people born in 1989-90 to 2000-01 respectively, suggest that some minority groups face a greater risk of being bullied than their peers.

For example, let’s look at the experiences of young people with disabilities. Researchers found that having any form of disability – be it developmental delay, long-standing limiting illness or special educational needs (SEN) – increases the risk of being bullied for both children and teenagers.

But it was 7-year-olds with SEN who suffered the most. These primary school pupils were twice as likely as other children to suffer from persistent bullying, when compared to their classmates without SEN.

What about when minority groups leave school? As the participants in Next Steps were last interviewed at age 20, it’s possible for researchers to look at minority groups’ experiences beyond the school years.

The DfE announcement makes a special mention of the experiences of sexual minorities, and the apparent decline in homophobic bullying in schools. However, recent findings from Next Steps show that lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) young people continue to face a greater risk of being bullied at age 20 – a 52 per cent chance compared to a 38 per cent chance for their heterosexual peers.

It is true that the situation has improved slightly for these young people since their school years. Between the ages of 14 and 16, those who later went on to identify as LGB had a 56 per cent chance of having been bullied in the past year, compared to a 45 per cent chance for their heterosexual peers.

However, LGB young people were at considerably greater risk of being bullied frequently – that is, once or more every fortnight – during secondary school. LGB young people were more than twice as likely as their heterosexual classmates to be regularly physically bullied and excluded from social groups.

]

]

The long-term effects

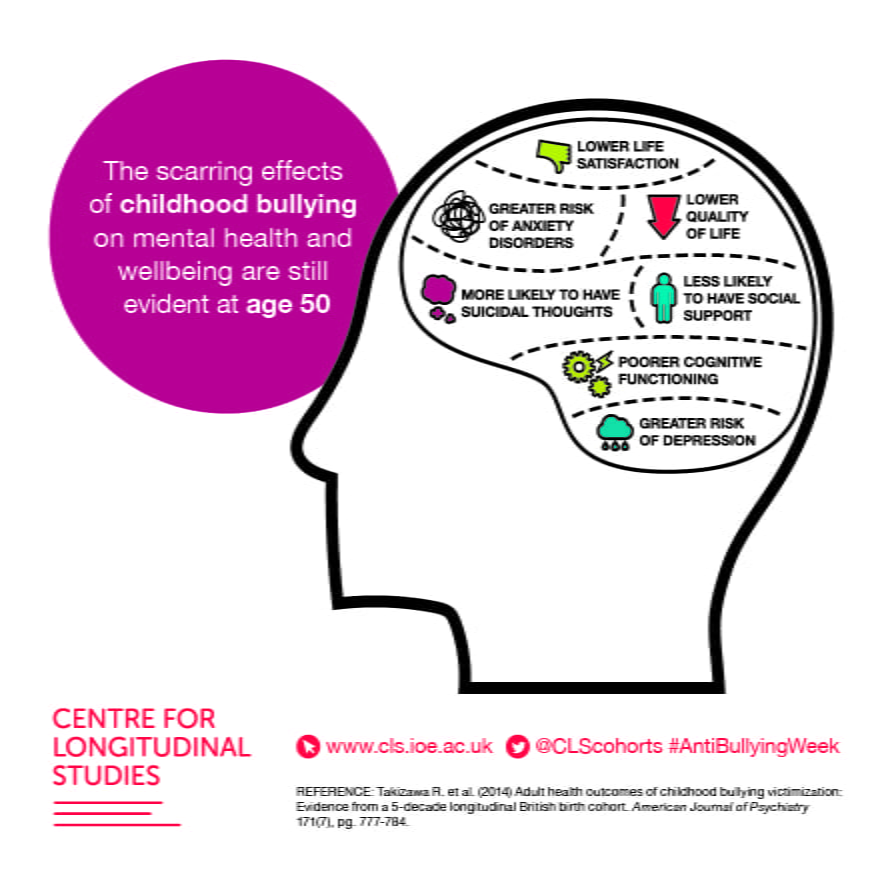

The National Child Development Study, which follows 17,000 people born across England, Scotland and Wales in 1958, has uncovered scarring effects of childhood bullying on mental and physical health right up to middle age.

At age 50, those who had been bullied in childhood were more likely to have anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts, and to be less satisfied with their lives than those who had never been bullied.

Bullied children were also more likely to suffer physical health problems in middle age. More than a quarter of women who were occasionally or frequently bullied as children were obese at age 45, compared to around one in five of those who had never been bullied. Men and women who suffered childhood bullying were also at greater risk of heart disease, diabetes and other illnesses.

Make a noise – Share your findings

The theme of this year’s Anti-Bullying Week is ‘Make a Noise’. As bullying becomes a growing area of research, there’s no better time to share the evidence with those campaigning for change. Get involved by sharing your findings on Twitter using the hashtag #AntiBullyingWeek, or follow @CLScohorts and @CLOSER_UK for more longitudinal evidence on bullying.

Close

Close