Teaching can be a pretty stressful job, particularly if you are at the sharp end of the accountability system. Pressure to increase pupil progress, or provide evidence of increased progress, can lead to long working hours and mounting tension.

Yet teachers often tell us that some schools they have worked in, or even different departments within the same school, do a much better job of protecting them from stress.

So what exactly makes the difference? And what can we learn

from the schools that do a good job?

Our research

Research suggests that the quality of a school’s working environment helps explain differences in job satisfaction and desire to quit among teachers. So, as part of our long-running project into teachers’ mental health and wellbeing, supported by the Nuffield Foundation, we teamed up with Teacher Development Trust to investigate whether school working environment might also explain differences in teacher stress.

A total of 300 teachers were surveyed from across seven volunteer schools. We asked each teacher to report on four different aspects of their working environment – leadership, workload/admin, collegiality, behaviour – captured using the Teachers’ Working Environment Scale (TWES). In addition, teachers reported their levels of stress in the workplace.

The headline findings

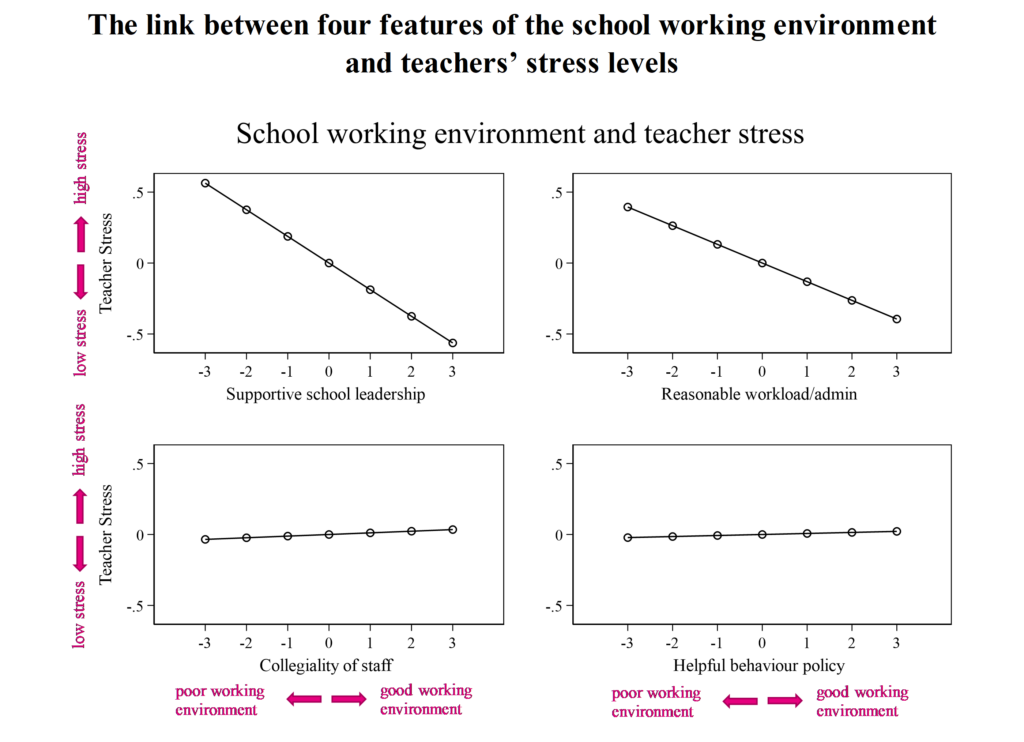

The charts below show our headline findings. Rather than showing each of the underlying datapoints, we have simply shown the lines of best fit.[1]

So, what do we learn? First of all, collegiality and behaviour policy show no clear relationship with teacher stress. Previous research suggests that they matter for job satisfaction and retention. But, according to the data we have collected, they are not associated with teachers’ stress levels.

In contrast, supportive school leadership and having a reasonable work/admin load are associated with reduced teacher stress.

The relationship in each of the charts is calculated holding the other three aspects of working environment fixed. So, for example, the top left chart is telling us that teachers with supportive leaders tend to have lower stress, even compared to teachers who otherwise have the same levels of workload, collegiality and behaviour policy in their school.[2]

What can we learn from this?

So we can be pretty confident that ‘supportive leadership’ and ‘workload/admin’ are related to teacher stress. But what do we learn from this about how to run a school? One way to get at this is to look more closely at what we mean by these terms.

Supportive leadership refers to the exercise of influence and direction setting in order to help teachers achieve their work goals. We measured this using questionnaire items such as “school leaders can be relied upon for support if asked” and “school leaders provide opportunities for teachers to participate in decision making”. School leaders looking to reduce stress and increase job satisfaction for teachers should focus on developing these aspects of their practice.

Workload here refers not to the overall number hours worked by teachers but to whether they perceive the specific tasks that they are required to do as hindrances. This is measured using questionnaire items such as “I am asked to do tasks which do not contribute to pupils’ education” and “data management gets in the way of teaching”. School leaders looking to reduce stress and increase job satisfaction for teachers should hence focus on minimising requirements that take teachers away from what they do best – educating pupils.

Notes

[1]: A value of 0 indicates average stress levels in our sample. A value of +0.5 indicates that a teacher is in the top third from stress levels in our sample and a value of -0.5 indicates that the teacher is in the bottom third.

[2]: We also get almost exactly the same relationship if we compare teachers who work in the same school, thus holding constant many other aspects of their shared working lives.

Close

Close