The First World War prompted an expansion of HE after devastating destruction. Can we draw lessons 100 years on?

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 24 July 2020

24 July 2020

Students coming to UK universities in September 2020 are facing a unique year: virtual freshers’ fairs, online lectures, social distancing and compulsory face coverings on campuses. Yet as lockdown eases, there is a renewed enthusiasm for continuing higher education – UCAS applications from UK school leavers are at an all time high.

A hundred years ago, there was a similar rush to the universities and colleges after the devastating disruption and loss of the First World War. A new open access article in the journal History, co-written with Sarah Hellawell and Daniel Laqua, is the first to examine an innovative government scholarship scheme for ex-service students. Between 1918 and 1923, the ‘Scheme for the Higher Education of Ex-Service Students’ broadened the social class base of UK universities and colleges, and marked a significant development in the provision of state funding for students’ higher education.

UCL Cloisters in the early 1920s showing photographs of the fallen and the roll of honour. Source: UCL Special Collections.

Immediately after the Armistice in November 1918, young people began planning their return to the universities and colleges they had left for military or civilian service. Many institutions, including University College London, ran an emergency year from January to August 1919, teaching through the vacation to enable students to complete their studies. A pressing shortage of school teachers drove a surge in demand for teacher training. At the London Day Training College (LDTC, as the IOE was then called) over 900 students enrolled on courses for 1921–22, three times the pre-war numbers. By 1922, the overall number of university students in England and Wales had almost doubled from the pre-war figures.

The early post-war years were challenging in many ways for universities and colleges, whose fee income had been affected by falling student rolls during the war. Buildings that had been requisitioned by the War Office were often not returned immediately or were given back in poor condition. The influx of students meant temporary huts had to be constructed for teaching, and lecture halls and laboratories were said to be ‘bulging’ with students. There was also an underlying sense of loss on campus, as universities and colleges began constructing memorials and developing rituals to remember the war dead. At University College, hundreds of photographs of the fallen – including some who had lost their lives to the Spanish Flu of 1918/19 – were put on public display in the Cloisters.

The ex-service scheme gave grants for fees and living costs to 27,772 ex-service students in England and Wales, while the Scottish Education Department awarded a further 5,848 grants and there was a separate scheme for Ireland. This was an unprecedented level of funding at a time when the entire student population of Britain and Ireland was less than 40,000. The grants were open to men only, despite some women applying. Later evaluations concluded that the scheme had enabled more students from working-class backgrounds to reach university than was usual at the time. The programme also helped students with war disabilities secure the training they needed for independent careers.

The impact of the war generation, both men and women, on student life was profound. Many of the grant recipients were older than average, sometimes married with children. The students were widely hailed as reinvigorating both academic and social life on campus, including restarting debating societies, student unions and varsity sports. Students sought to re-establish international links by setting up branches of the League of Nations Union and fundraising to support students in need across Europe.

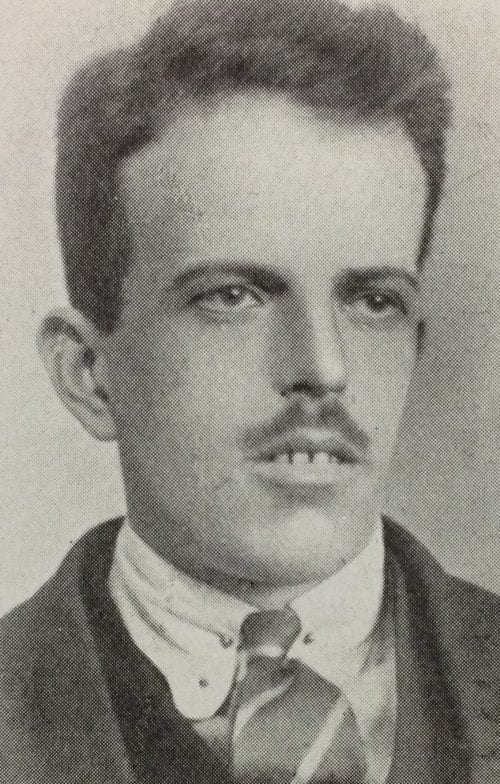

- Charles Judd photographed when President of the LDTC Union Society. Source: UCL Special Collections.

- Violet Anderson. Source: UCL Special Collections

One student who encapsulates some of these trends was Charles Wilfred Judd (1896-1974). Judd received a grant to study the ‘four-year’ course at the London Day Training College, which included taking his BA degree at University College followed by teacher training. Judd received an annual maintenanceallowance of £120 and was eligible to apply for occasional book grants of £5. Judd served as president of the LDTC students’ union and later as the first honorary secretary of the National Union of Students (NUS), beginning a long career in internationalism and education. According to the student record card we hold in the IOE archives, Judd had ‘not only displayed quite remarkable energy and tact, but has done work of international importance in bringing together in brotherly association University students all over Europe.’ Similarly, UCL botany student and women’s union president Violet Anderson was a delegate at the Prague meeting of the new International Confederation of Students, which helped precipitate the formation of the NUS. Back at UCL, Anderson helped form a new Inter-Union Standing Committee to coordinate activities between the still separate women’s and men’s unions.

The foundation of the National Union of Students in 1922 might be seen as the crowning achievement of the ex-service generation. As we move to a so-called ‘new normal’, taking a long view of how the university sector has coped with loss and reconstruction in the past might provide some inspiration for the future.

This article is based on a research project funded by the Everyday Lives in War AHRC World War One Engagement Centre and undertaken with the National Union of Students and the Workers’ Educational Association. The Society for Education Studies has supported additional research. Read the full paper here. You can learn more about the impact of the First World War on UCL in this Lunch Hour Lecture.

Close

Close